China's Balance of Payments (Part I): From the Trade War to a "Positive" COVID Shock

What initially looked like a hit to global supply chains in China, turned into a global shock that ultimately supported China's external balance significantly

At the start of 2020 the fallout from trade war between the US and China in 2019 and elevated tariffs weighed heavily on US imports from China. But the effect on China’s overall trade position was limited (partly due to trade diversion), and China’s trade performance was in any case dominated by the COVID shock in 2020. Interestingly, what initially looked like a major negative hit to China’s export machine and role in global supply chains reversed in Q2. All told, the COVID shock ended up massively boosting China’s external balance via strong goods exports and dramatically curtailed outbound tourism. These forces have been key to a bullish trend for the Chinese currency over the last 6-7 months.

From Trade War Truce to the Pandemic Shock

2020 was a wild year for global macro, but one of the most important—and to many observers surprising—trends was that of the Chinese balance of payments. As the year began, the US and China appeared to be moving towards a detente in the trade war after several years of steady escalation and bruising negotiations.

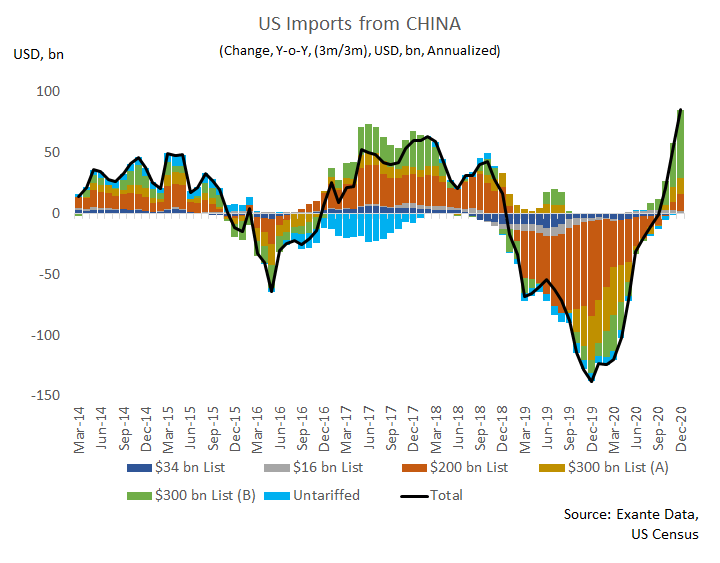

Under both the impact of tariffs already imposed, and the threat of additional rounds of escalation, US imports from China were contracting sharply as 2020 began.

Notably, total Chinese exports contracted by less than exports to the US as a result of trade diversion and substitution (but that is a topic for another post.)

By late 2019, the outlines of what would become the Phase 1 trade deal had begun to emerge. As a reminder, before Phase 1, the US had imposed effective tariffs of $50 at 25% (tranches 1 & 2, aka the $34bn and $16bn lists), $200 at 25% (tranche 3 aka the $200bn list) and $112 at 15% (tranche 4A). Late in 2019 the threat loomed that the US would impose tariffs on an additional $155 at 15% (tranche 4B). However under the Phase 1 deal, the US removed the threat of of tariffs on 4B altogether and then cut the tariff rate on 4A from 15% to 7.5% starting in February 2020. The chart below shows US imports from China by tariff list/tranche through December 2020.

Yet, as the ink on the agreement was still drying (link), Chinese authorities imposed the first lockdowns in Wuhan on January 23rd in the face of the coronavirus. Over the next several weeks, as lockdowns spread in China it became clear that the hit to Chinese economic activity (including both imports and exports as well as tourism) would be severe. Authorities didn’t publish monthly trade statistics for January and February until early March (combining both months into a single print and ruining analyst’s seasonal adjustments everywhere).

As the pandemic and associated lockdowns spread beyond China it became clear that what initially appeared a transient and localized supply shock (albeit one at the heart of global supply chains) was in fact a massive global demand shock. Surely such a demand shock would also weigh heavily on China’s export intensive economy?

Or maybe not.

While China did go on to record a current account deficit in 1Q20 (only its fourth quarterly deficit print since 1998), by the early summer it was clear—in an ironic and perverse twist of fate—that China might actually be one of the pandemic’s biggest economic beneficiaries (at least so far as the balance of payments was concerned).

Driver’s of China’s current account strength in 2020

There were a number of fundamental factors that provided support to China’s current account in 2020 against the backdrop of the pandemic.

Supply: China succeeded in containing the virus and reopening the economy. By April mobility was nearly back to pre-pandemic levels and case counts were dwindling. This allowed production and exports to resume after a long and severe lockdown period. But, importantly, Chinese authorities were able to stand-up a remarkably successful infrastructure for testing, tracing, tracking and containing the virus. This would enable them to avoid re-imposing similarly draconian lockdowns as the year progressed and avoid the successive waves of the outbreak seen in other countries. In addition, China’s macroeconomic stabilization policies focused on channeling credit to businesses, encouraging investment and supporting production.

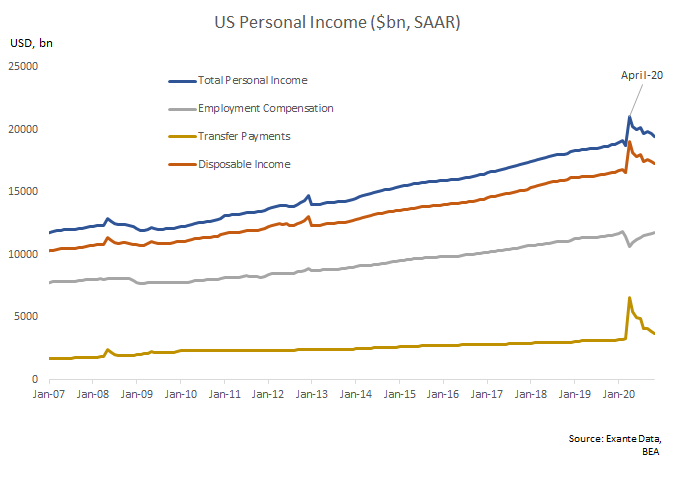

Global Demand: In contrast to China’s “supply side” stimulus, extraordinary fiscal accommodation in many other economies (especially in the US) provided support to households and consumers through direct fiscal transfers and income support. Hence, despite the hit to employment compensation from the recession, US household income actually rose (in aggregate at least) in 2020.

Expenditure switching/forced savings: One of the unique aspects of the COVID induced recession has been the disproportionate impact on services—both tradeable and non-tradeable. On the tradeable services side, this has been most visible via tourism flows. China is traditionally a large net importer of tourism and travel services, while Europe and to a lesser extent the US are net exporters. With international tourism mostly shut off, this has provided a major boost to China’s current account surplus and been a substantial drag on the current account balances of the US and EU (among others). The chart below shows the narrowing in China’s tourism deficit.

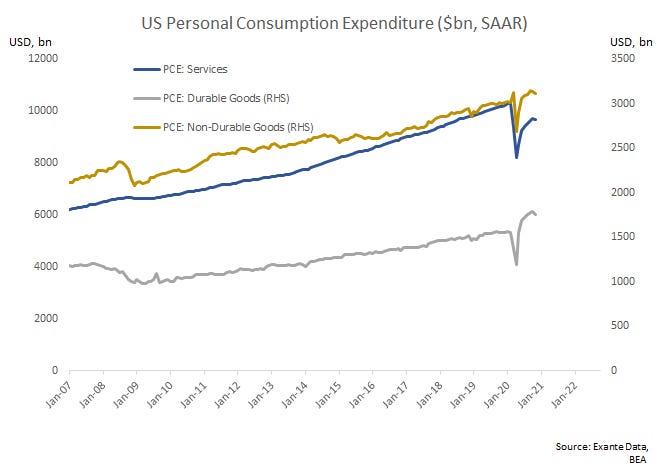

There has also been expenditure switching away from services and towards goods. With the additional income support provided by fiscal stimulus, and unable to spend on services due to the virus, US consumer expenditure on goods surged above pre-pandemic levels. Services expenditure remains depressed by contrast, and, because services make up the lion’s share of total expenditure, personal savings have increased dramatically in 2020 (again, in aggregate).

Finally, there has been pandemic related demand for specific goods (link) that China tends to export a lot of including: PPE, medical equipment, pharmaceuticals and electronics and office equipment/furniture (the latter in high demand for those “working from home”).

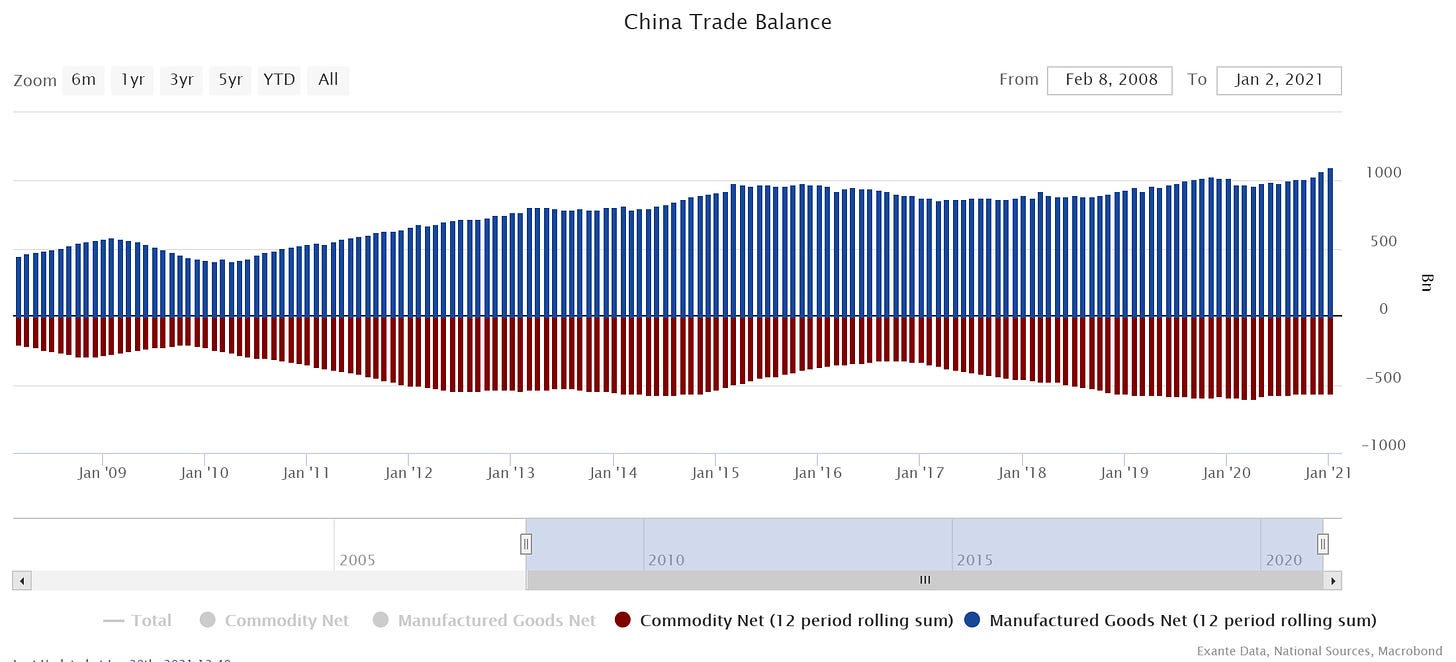

Terms of trade: As a major commodity importer and primarily a manufacturing exporter, China also benefitted from a substantial terms of trade tailwind in 2020. For instance, the IMF estimates China experienced an 8.3% improvement its terms of trade in 2020. The chart below shows the the 12 month rolling sum of net commodity and manufacturing trade.

While it may not look impressive, the commodity balance improved by roughly $40bn (0.3% of GDP) on an annualized basis even as import volumes remained strong amid strategic stockpiling and investment-led demand growth. Copper import volumes, for example, reached record highs in 2020.

A bumper year

The bottom line is that, defying expectations from the trade war, China benefitted from a number of positive forces from Q2 which contributed to a sharp improvement in the current account surplus in 2020: Strong virus containment measures allowing near-normal activity from mid-year; global fiscal expansion; expenditure switching from services to goods by major trading partners; lower tourist service debits, and a positive terms of trade shock.

Overall, these shocks combined to drove an improvement in China’s current account surplus from $141bn in 2019 to an estimated $332bn billion last year, or about 2.2 percent of GDP (based on IMF GDP for 2020 of $15tn).

On top of this surplus, relatively attractive yields and a stable currency brought record portfolio bond inflows inflows in 2020 which required additional recycling. This is the topic of the next post which will focus on dynamics in China’s financial account.