Could there be a Eurosystem liquidity crisis (Part II): Could NCBs run short of euros?

National central banks could face a liquidity shortfall due to unconventional monetary policy

National Central Banks in the Eurosystem could run out of euros to pay for the cost of monetary policy, which demonstrates how NCBs ultimately need quasi-fiscal support to conduct their activities—and the ECB is engaging in de facto transfers across the Eurozone.

In a previous post we noted how National Central Banks (NCBs) in the Eurosystem started to provision for interest rate risk from the normalisation of monetary policy shortly after the Asset Purchase Program (APP) was initiated by the European Central Bank (ECB). See Part I.

More recently, the ECB has initiated a “dual rates” policy whereby the interest rate on lending operations are below the interest rate on deposits—implying a loss to monetary income in the conduct of this policy. While in its early stages still, some are advocating for even more aggressive implementation of this policy innovation—and larger associated losses.

For example, Megan Greene and Eric Lonergan have argued that dual rates “give central banks limitless firepower.” This would indeed be the case if Lagarde’s insistence were true that as “the sole issuer of euro-denominated central bank money, the euro system will always be able to generate additional liquidity as needed.” However, institutional constraints on NCBs mean they cannot simply print their way out of a financial hole—at least not under the existing arrangements. Moreover, even if remote, it is even possible that without quasi-fiscal support, a NCBs could experience a liquidity event—meaning they are unable to transfer the resources necessary to pay for the cost of conducting monetary policy.

We explain how this could arise below. The key point is that is shows that there are limits to unconventional monetary policy given existing institutional constraints.

Eurosystem monetary income and NCB transfers

How might a liquidity crisis occur in the conduct of monetary policy? Consider how NCBs of the Eurosystem share net monetary income due to repos, bank deposits, and from coupons on the shared part of the asset purchase program (APP.) This results in a series of transfers related to monetary operations across the system. In addition, each NCB enjoys their own coupons from the non-shared part of the Public Sector Purchase Program (PSPP, i.e., 90% of the total)

Each NCB can therefore make two transfers per period as appropriate. First, there is a transfer to, or receipt from, the system relating to the sharing of monetary income. Second, there are transfers to beneficial shareholders—usually the resident government—due to net interest income after transfers related to monetary income.

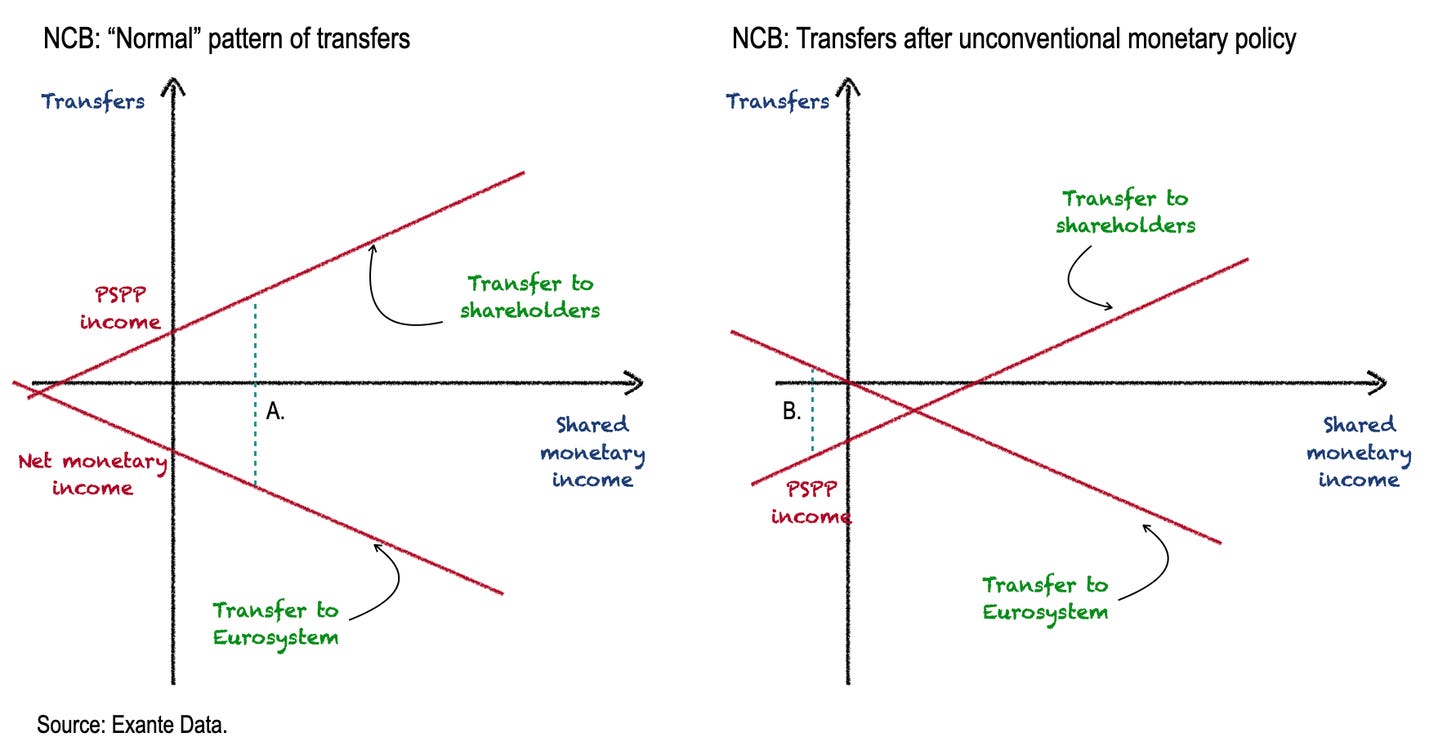

Assuming income is transferred in full in each period, the chart below illustrates the transfer to shareholders which is increasing in the shared monetary income and crosses the y-axis at non-shared PSPP income. The higher is shared monetary income, the higher are transfers to shareholders. It also shows the transfers to the Eurosystem as a decreasing function of shared monetary income (a negative transfer being a receipt from the system.) The slope of each of these lines is equal and opposite, determined by the capital key share. It is straightforward to derive these relations from the flow budget constraint of NCBs.

The left chart below shows these transfers for a hypothetical “normal case” when the NCB makes positive income from PSPP holdings (i.e., a positive coupon) and makes transfers to domestic banks due to monetary policy (say because of a positive deposit rate and surplus excess liquidity.) This approximates Germany’s position in recent years. In this case, we can read off the transfers from the system on account of monetary income (at A.) Some goes to finance the interest on domestic bank deposits with the NCB, the rest is transferred to shareholders. There is positive seigniorage income to be shared.

Next consider, as on the right, a situation where the PSPP has been ongoing for many years at negative yields, bringing losses as government bonds are redeemed—so the transfers to shareholder line crosses below the x-axis. There are no coupons to contribute to the cost of policy. Moreover, suppose that due to TLTRO operations at rates below the deposit rate to support bank lending, the system begins to make negative monetary income—meaning monetary policy actions are loss making for the system as a whole at B., if not for this NCB alone.

Now, this is admittedly a stylised case. But the NCB has to make a positive cash transfer to the Eurosystem related to losses due to monetary policy while making overall losses on PSPP. This has not yet happened and may be many years away. But, due to these losses a transfer from shareholders becomes necessary—otherwise the NCB has to run down capital. Notably, this transfer is necessary not only to make up for PSPP losses, but also to transfer money to the rest of the system for the cost of implementing the dual rate policy. In this extreme case, it is as if the German government is transferring resources to the Bundesbank to pay for a repo conducted at a negative rate in, say, Spain—that is, a de facto transfer to a Spanish bank and therefore Spanish borrowers from the German government.

Of course, you might say, in this case the NCB would just run down capital—selling liquid assets—to make the transfer of monetary income to the rest of the system rather than call upon a transfer from owners. Perhaps. But over a long enough horizon, NCB capital would eventually be eroded to the point where such liquid assets are exhausted or alternatively the shareholder is forced to provide a recapitalisation. Hence the provisions noted in the previous post.

What if the NCB is indeed short of capital, making losses on PSPP holdings, and is required to transfer cash to the Eurosystem to pay for monetary policy? If the government “owner” does not provide a recap and accompanying coupon, or make a direct transfer from the budget, then there is no way to make this transfer. NCBs cannot simply create euro liquidity. If they could, the euro crisis would have been only a trifling event. Instead, the NCB would indeed be facing a liquidity (if not technically a solvency) crisis. There is no way they themselves can create the euros to pay for the cost of monetary policy without explicit fiscal support. In this way, MEP Zanni’s question cannot be so simply brushed aside.

END.