EM QE: Here to stay?

Does the pandemic mark the beginning of a new regime of balance sheet activism by EM central banks; or was the pandemic intervention only a one off?

Once the domain of developed market (DM) currencies, quantitative easing (QE) during the pandemic has gone mainstream. Emerging markets (EMs) initiated, largely for the first time, their own QE programs during the past year. But the size and impact on asset prices varied across jurisdictions. But is EM QE here to stay, or was it only a one-off?

One of the more unexpected policy innovations during the global pandemic has been the emergence, beyond developed markets, of quantitative easing (QE) as a policy tool amongst emerging markets. Indeed, EM central banks (CBs) saw their balance sheets grow at unprecedented rates over the past year—largely due to the purchase of domestic public debt (QE).

Cross-country QE

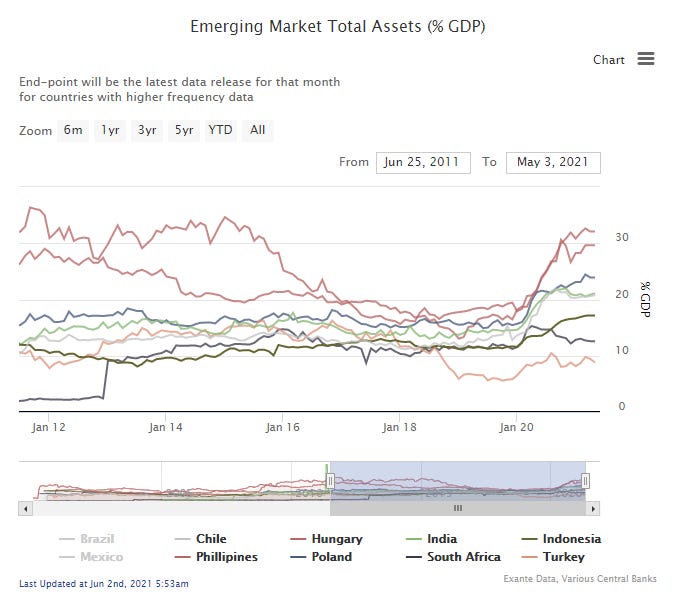

The chart below from Exante Data’s Global Liquidity Monitor shows the expansion in balance sheet for select emerging markets. While total CB assets were broadly stable or on a downward trend post-GFC, given nominal GDP growth, during the pandemic many EM CBs witnessed rapid balance sheet expansion—though not on the scale of DM counterparts.

CBs in both the Philippines and Hungary today have balance sheets reaching 30% of GDP. Others now exceed 20% of GDP, such as India and Poland. Only South Africa’s central bank quickly wound the balance sheet expansion witnessed in the first half of 2020 while Turkey lags (on balance of payments pressure).

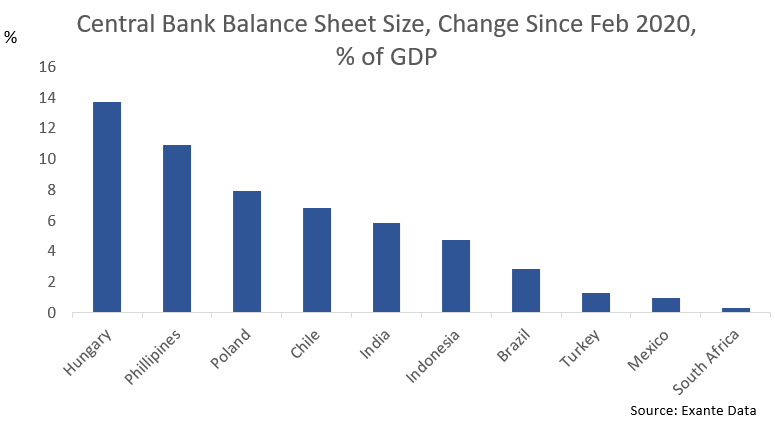

Looking at the change in balance sheet size, Hungary and the Philippines have clearly seen the largest expansions at over 10% of GDP; Poland, Chile India and Indonesia have also seen balance sheet expansion over 5% of GDP. Turkey, Mexico and South Africa lag at below 2% of GDP.

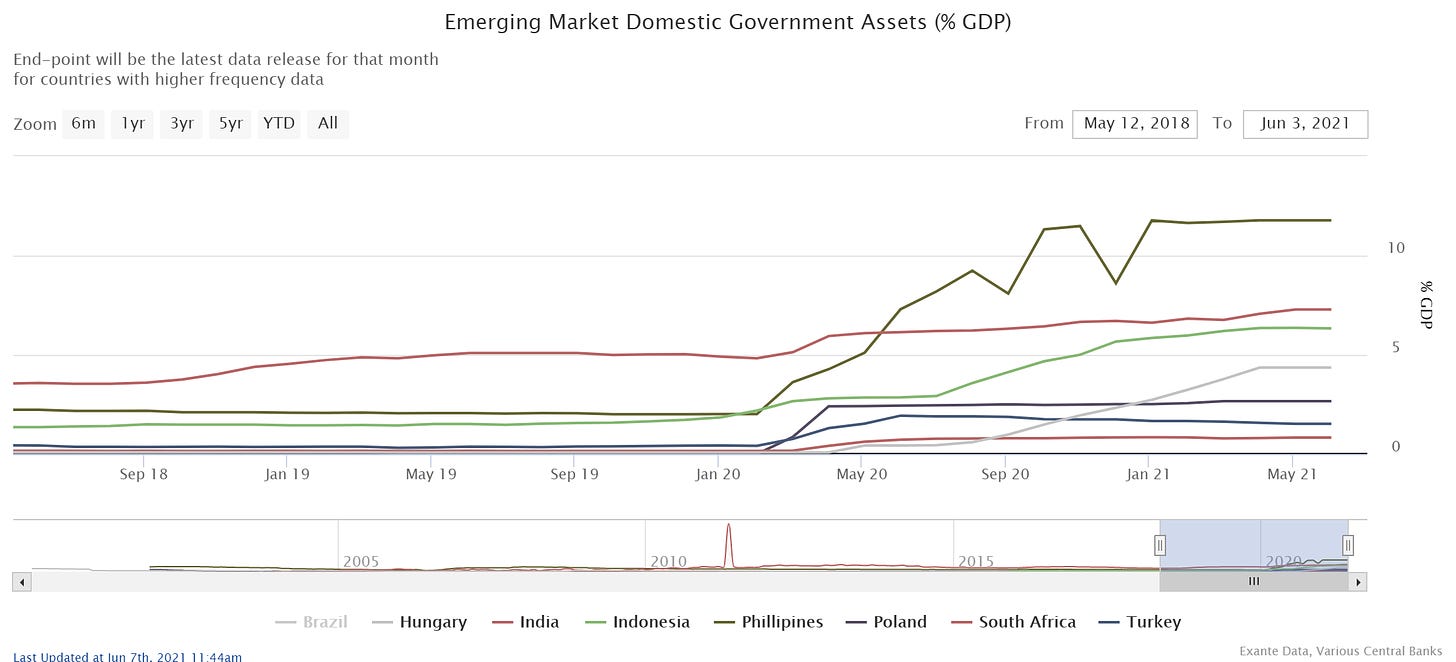

Much of this growth was driven by QE. Our Global Liquidity Monitor shows the Philippines’s holdings of domestic government debt have increased by around 9ppts of GDP. While most countries have seen their ventures into unconventional monetary policy stabilize in 2021, some like India may see further expansion this year.

Where the Fed goes, others follow

In general, EM QE announcements came later than DM equivalents, after exchange rate and fixed income pressure had already peaked just after mid-March, 2020. They also followed the initiation of the Fed’s dollar swap lines, expanded to some EMs on 19th March, during peak pandemic stress.

However, whereas some DM central banks announced unlimited buying programs (the Fed and BOJ), EM QE programs were generally of limited size and duration.

The timing of QE announcements is likely crucial, therefore. EM QE was initiated (mainly) after the Fed and other DM central banks had already acted against liquidity concerns and substantial fiscal packages were within sight helping to put a bottom on asset prices after the initial pandemic panic. As such, global growth expectations would soon stabilize; capital flight from peripheral economies was already complete—and inflows about to re-emerge.

For example, most EM crosses had already depreciated sharply by the time EM CBs announced their QE plans. Asset prices had already adjusted. EM CB buying was initiated at a time when domestic assets were cheap for non-resident investors.

Crowding out

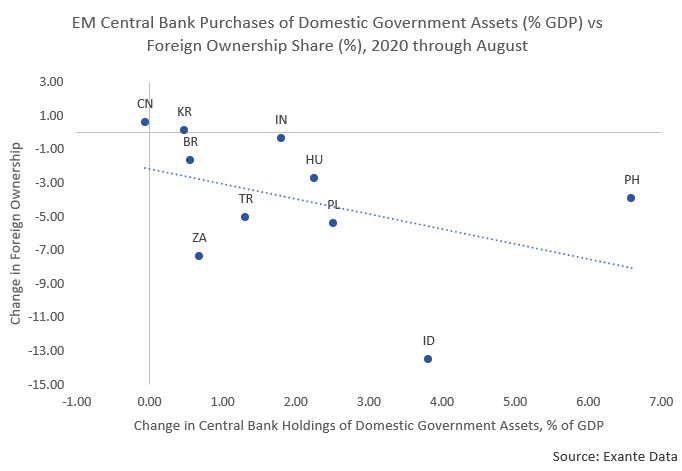

There are signs that these policies impacted the ownership structure of EM sovereign debt. For example, there has been a decrease in foreign ownership of domestic debt among countries with larger QE programs, implying that central banks were able to crowd-out foreign investors (much as happened in the Eurozone post-APP.)

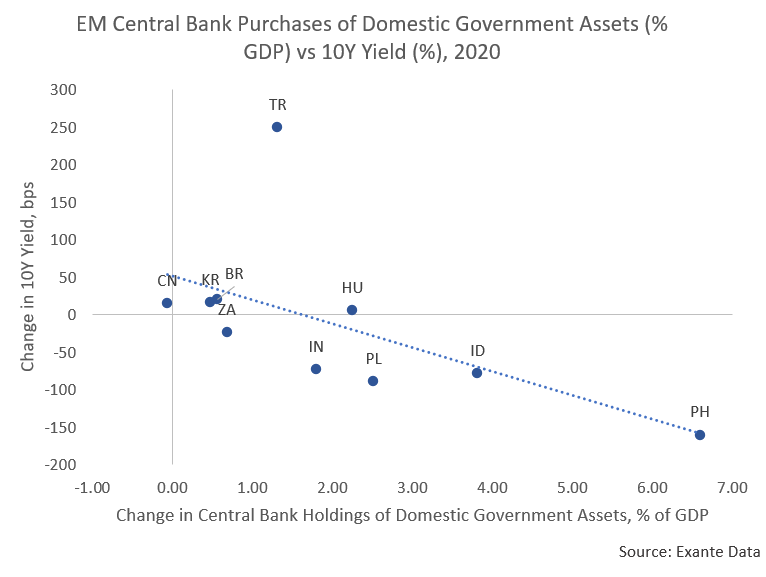

Moreover, QE has also appears to have impacted local rates as countries with the largest purchases of domestic government assets have seen the largest decreases in the 10y yield, although there could be some two-way causality at play here.

Perhaps most important, however, is that such CB buying was initiated at a time when private saving rates were accelerating.

The chart below shows that increases in private saving-investment balances were positively correlated with the size of EM QE. The impact on private saving is hardly surprising, as these are the mirror of fiscal deficits. But such domestic saving implies the impact on EM current accounts of the fiscal response during the pandemic was minimal; there was no external financing gap created.

So central bank buying of domestic assets was happening into a captive market for domestic saving vehicles from private actors. Given that resident portfolios did not seek foreign assets for safety, QE could occur without weakening exchange rates and creating inflation risk.

What happens next?

Given larger EM central bank balance sheets, what happens next? Will EM central banks live with structurally larger liquidity? Or will such expansion be reversed?

At one level it will matter how the surplus private saving feeds into external imbalances during any recovery, generating exchange rate weakness and possible inflation pressure. If this were the case, there could be de facto sterilization through reserve sales, mopping up the liquidity created.

To date, however, there are no signs of such pressure—if anything, reserve accumulation has begun once more. Those experiencing capital inflows during the recovery might undertake intervention to prevent real exchange rate appreciation. This could then be combined with sales of domestic assets to ‘mop up’ this excess liquidity. Indeed we have been seeing the latter in a number of places, such as Indonesia where the government has increasingly incentivized reverse-repos (taking bank reserves in exchange for government bonds).

Conclusion: EM QE: More Exception than Rule?

Does the apparent success of these policies means they will remain part of the EM CB toolkit? Or will they fall away as the global economy normalizes?

Perhaps the most unique aspect of the Covid crisis was the repression of private consumption, particularly on services, creating a captive pool of domestic saving. Although this effect was most important in DM markets, it was also relevant in EM.

Combined with relatively strong fiscal responses, households and businesses have not (yet) witnessed an erosion of their balance sheets. Private sectors across EM (and G10) were thus an important force sustaining domestic demand for assets, helping keep yields low.

It might be that the circumstances that made EM QE possible during the pandemic were exceptional, implying these tools should be used only sparingly in the future. Was the fact that it was a global shock and not idiosyncratic the key of EM QE?

It also remains to be seen how large balance sheets will impact the shape of EM recovery and how unwinding of QE may affect future financial conditions. These will be important dynamics to watch as the world economy attempts to return to normal.

Finally, some of the countries that moved the most aggressively on QE (and monetary policy overall), such as Hungary, are facing inflationary challenges at the moment. The transitory vs permanent debate is not settled yet. The final verdict to that debate will also be a big part of the answer to whether whether EM QE will ultimately be deemed a success; and whether such quantitative easing policies will become normalized, and a part of standard operations for EM central banks in the future.