How big are Bank of England QE losses?

APF losses may exceed GBP270bn over the 11 years with maybe GBP100bn of this due to secondary market sales

Press coverage of Bank of England reporting of possible APF losses has failed to notice that losses over the next decade will exceed GBP250bn—that is, even more than the reported GBP150bn cumulative losses since the program began;

And there is no recognition that this figure includes both net interest income losses as well as losses from secondary market sales;

The latter could be as much as GBP100bn (4% of GDP). But is realising these losses up front really necessary?

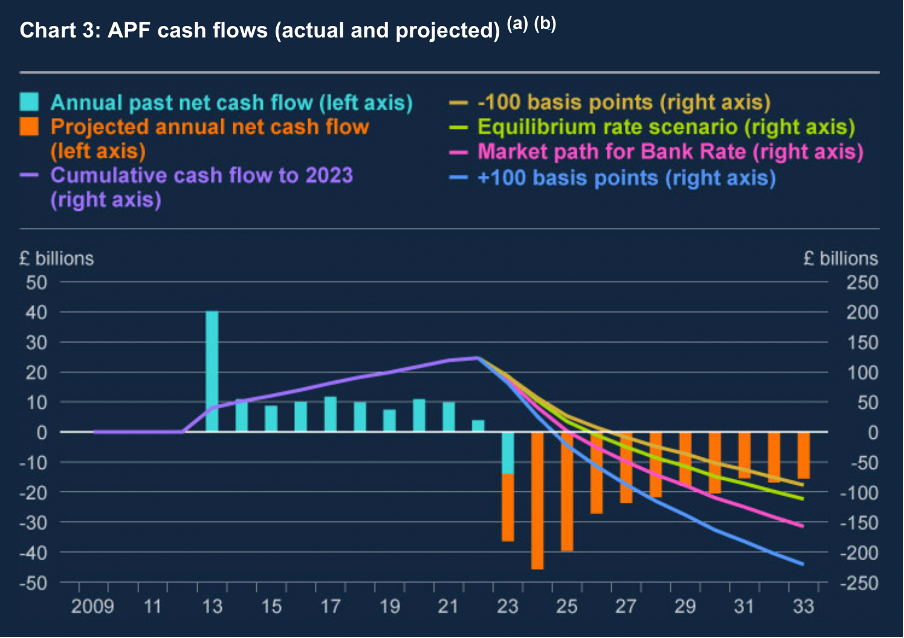

There has been excited coverage of the Bank of England’s projection, as part of the latest quarterly asset purchase facility (APF) report, of the ever-growing losses due to that facility. The Bank’s report includes a chart, reproduced below, on the cumulative APF losses. This has resulted in newspaper headlines noting that losses will amount to GBP150bn (see the FT and Guardian, for example.)

GBP270bn losses ahead

It is disappointing that newspapers have fallen for the Bank’s deliberate obfuscation of future losses by netting out past cash gains.

Indeed, the total losses in the chart, giving the GBP150bn figure, are shown cumulatively since 2011—whereas the losses since QT began are from the high watermark in 2022 to the endpoint shown here in 2033. The change in this cumulative cash flow, eyeballing the chart, looks to exceed GBP270bn under the market path for rates. Alternatively, summing the annual (negative) cash flow suggests this could be closer to GBP280bn.

In other words, the GBP150bn in losses from the APF is net of past gains of GBP125bn.

Of course, the program as a whole should be judged from start to finish—as history no doubt will.

But from where we sit today, losses over the period 2022 to 2033 might be GBP270bn. And it is GBP270bn that is a reasonable baseline for the impact the fiscal accounts over the next decade and associated net gilt issuance.

The origin of losses?

Recognition of such (likely) losses ought to prompt, for full transparency, the decomposition between those due to the net interest income (i.e., coupon income less interest on reserves and principal losses at maturity) versus realised losses from secondary market gilt sales.

The former, net interest flows, represent arguably “necessary” losses as the policy rate needs a floor at the short end, through payment of interest on bank reserves, to push the Bank’s policy stance across the yield curve.

The latter, due to gilt sales, are perhaps less necessary as they represent those losses crystallised as the Bank speeds up balance sheet shrinkage. And such shrinkage is apparently not necessary for today’s policy stance.

We are constantly told, as last week, that the Monetary Policy “Committee has a preference to use Bank Rate as its active policy tool when adjusting the stance of monetary policy. … QT should be thought of as operating in the background.”

The reason for accelerating balance sheet shrinkage through sales is explained as providing room for future balance sheet expansion “if successive policy cycles meet the effective lower bound on interest rates.”

So, secondary market sales are not about fighting inflation now, but are a form of insurance policy to fight deflation later through QE.

It would be nice to know how much this insurance policy will cost the taxpayer.

This could be done by showing the projected cumulative loss under organic balance sheet compression alone versus that including outright sales.

What losses on secondary market sales?

We can hazard a guess at these losses. But only a guess.

Last year, we calculated the loss from organic balance sheet reduction alone with Bank Rate reaching 600bps before dropping off to 350bps. This came in about GBP160bn through 2033. This scenario is close to the Bank’s latest baseline for peak Bank Rate for this quarterly update, though the terminal rate might be too low. If this terminal rate is too low it would understate the net interest bill. Against this, secondary market sales are not assumed and would compress this net interest bill somewhat.

Let’s take this previous scenario to be ballpark correct.

It implies losses embedded in the Bank’s forecast from secondary market sales over the next decade of about GBP100bn (nearly 4% of GDP) on the basis of sales of GBP400bn.

That is, secondary market sales of gilts are being undertaken at about 25% loss compared to the purchase price.

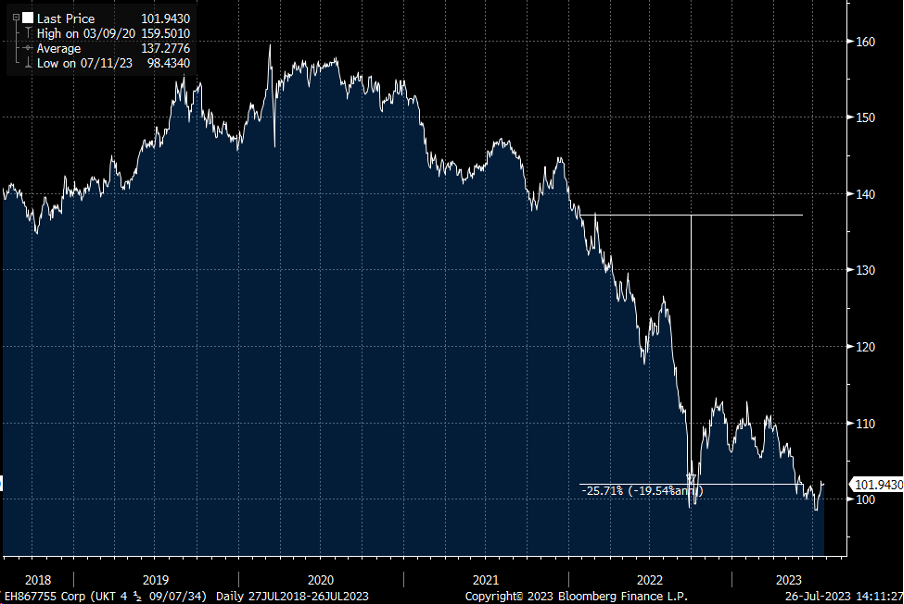

A gilt cross-check

We can check this logic by looking at a representative gilt accumulated by the BOE during the APF.

For example, the Bank owns GBP22.4bn in face value of the Sept. 2034 gilt (ISIN: GB00B52WS153) with a coupon of 4½ percent. The average price paid during APF purchases was 37% above par. The bond today is trading at a price of about 102 which is roughly 25% below the average price paid.

So the Bank is indeed sitting on mark-to-market losses of about 25%.

What’s the rush?

If the Bank’s argument that balance sheet “space” is needed for future QE made sense, then perhaps realising up front a loss of 25% on bonds, amounting to 4% of GDP over the next decade, is worthwhile. But it is hard to imagine a situation arising where QE is constrained by the outstanding stock of available gilts.

After all, previous QE rounds were associated with widening fiscal deficits and net issuance. And in any case, the lessons from past QE experience suggest short-sharp interventions targeted at financial market disruptions are the way to proceed—that long periods of bond buying does little to support the price stability objective in any case.

In which case, QE will not be constrained. Surely the post-mini budget gilt market stress showed this to be the case?

And if the need for early balance sheet contraction is not urgent, then when would gilt sales make most sense?

Curiously, selling when the Bank is poised to enter the next cutting cycle would make more sense as gilts will be rallying in price—and losses can be contained if not eliminated.

In other words, the Bank could set up their balance sheet contraction to better suit demand for safe assets.

The Bank has already acknowledged that QT will likely continue, at least initially, when rates are being cut. They could go further still and hold off on gilt sales until this time—and only then if the financial market situation allows.

The content in this piece is partly based on proprietary analysis that Exante Data does for institutional clients as part of its full macro strategy and flow analytics services. The content offered here differs significantly from Exante Data’s full service and is less technical as it aims to provide a more medium-term policy relevant perspective. The opinions and analytics expressed in this piece are those of the author alone and may not be those of Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC. The content of this piece and the opinions expressed herein are independent of any work Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC does and communicates to its clients.

Exante Advisors, LLC & Exante Data, Inc. Disclaimer

Exante Data delivers proprietary data and innovative analytics to investors globally. The vision of exante data is to improve markets strategy via new technologies. We provide reasoned answers to the most difficult markets questions, before the consensus.

This communication is provided for your informational purposes only. In making any investment decision, you must rely on your own examination of the securities and the terms of the offering. The contents of this communication does not constitute legal, tax, investment or other advice, or a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. Exante Advisors, LLC, Exante Data, Inc. and their affiliates (together, "Exante") do not warrant that information provided herein is correct, accurate, timely, error-free, or otherwise reliable. EXANTE HEREBY DISCLAIMS ANY WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.