European Central Bank (ECB) staff are frustrated under the leadership of Christine Lagarde according to headlines last week.

On Monday Politico broke the story of a trade union survey in which about 50% of respondents ranked Lagarde’s “overall performance in the first half of her eight-year term as ‘very poor’ or ‘poor.’”

The main complaint being that Lagarde is “wading too deeply into politics and using the ECB to boost her personal agenda.” Quoting one staff member, Politico noted that whereas “Mario Draghi was there for the ECB … the ECB seems to be there for Christine Lagarde.”

Comparisons are odious

As the story notes, this assessment contrasts with the support by ECB staff for predecessors Draghi and Trichet. Then again, comparisons are odious.

It is certainly unfair to compare a mid-term survey, as Lagarde’s, to the end-of-term staff reviews of her predecessors. For one thing, the recent burst of inflation has left ECB staffers in real terms worse off and likely frustrated. For another, mid-term surveys are more likely to provoke an unrepresentative sample hoping to have their voices heard—and, as the FT points out, citing ECB sources, the same person could have completed the survey multiple times.

So perhaps we should not take this survey too seriously.

In any case, investors need to cut through the gossip and try to understand the extent to which the story illuminates internal processes and decision-making.

What does this say about policymaking that could impact future asset prices? Or can the story be safely ignored?

A mid-term review

An alternative mid-term score card based on ECB policy-making since end-2019 would note the following events:

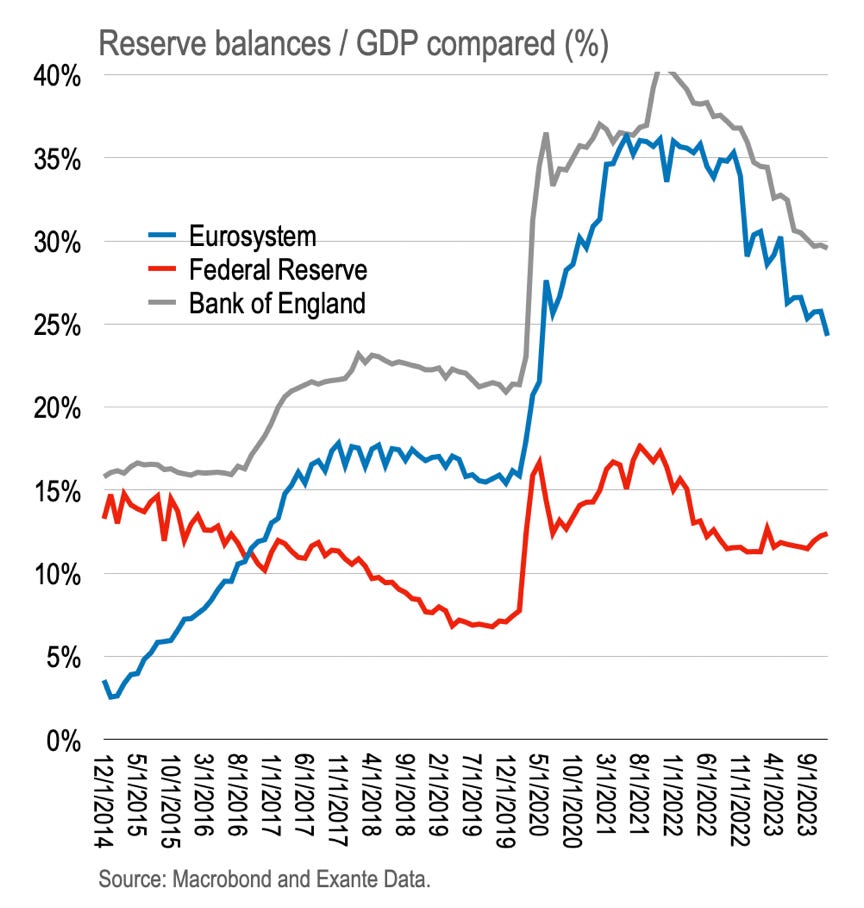

Asset purchase fumble. On 12 March 2020, just as the pandemic was taking hold, limp balance sheet expansion through the Asset Purchase Program (APP) of EUR120 billion was announced, contrasting with the aggressive actions of the Bank of England and Fed. In addition, the press conference included the claim the ECB is “not here to close the spreads,” a phrase subsequently caveated by a footnote in the transcript, drawing on a hastily arranged interview with CNBC to calm the market reaction.* This was followed on 18 March, less than a week later, by the announcement of an aggressive balance sheet expansion of EUR750 billion, later expanded further still, under the more flexible Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) underlining the flawed initial response.

Retrospective TLTRO adjustment. The earlier March meeting also included revised terms of support for bank lending through the Targeted Long-Term Repo Operations (TLTROs). Not only was this funding made available at as much as 50bps below the deposit rate (so perhaps -100bps meaning banks were paid to borrow) but the cost of funding in later years was linked to “the average of the deposit rate over the life of the TLTRO3” (discussed previously here.) As such, even as the deposit rate increased during the tightening cycle, the interest paid by banks was slow to adjust while the interest on reserves with the Eurosystem was flexible. As policy normalised, banks were set to make a substantial and unexpected profit from the TLTRO scheme. To avoid this windfall, the ECB retrospectively changed the terms of TLTRO borrowing on 22 October 2022 under the guise of “ensur[ing] consistency with the broader monetary policy.”

Forward misguidance. The initial plan to ensure an escape from the liquidity trap, hatched pre-pandemic and re-worked in the Strategy Review, was to lean on forward guidance to sustain low rates across the yield curve through “especially forceful or persistent monetary policy measures to avoid negative deviations from the inflation target becoming entrenched.” In practice this meant committing keep interest rates low whereby, for example, in July 2021 the Governing Council:

“expects the key ECB interest rates to remain at their present or lower levels until it sees inflation reaching two per cent well ahead of the end of its projection horizon and durably for the rest of the projection horizon, and it judges that realised progress in underlying inflation is sufficiently advanced to be consistent with inflation stabilising at two per cent over the medium term. This may also imply a transitory period in which inflation is moderately above target.”

The problem being that this was set in the middle of a global pandemic at the end of which a global monetary stock imbalance would need to be unwound through price level adjustment—and was further unsettled shortly after by an energy shock unrivalled since the 1970s. Both would provide boost to prices, making the projection horizon a tricky metric for understanding inflation dynamics. And in any case, since ECB staff proved particularly challenged in picking up the persistence of the inflation shock, forecasts were consistently beat to the upside within weeks of policy meetings, causing the Governing Council to panic into rate hikes as spot inflation out-turns were taken as a signal of medium-term inflation prospects. The result was the rapid abandonment of forward guidance mid-2022 and the pre-announcement of a 25bps rate increase in July that was itself reneged on in favour of a 50bps increase when the time came. Confirming the demise of this approach, Lagarde recently told the Financial Times when reflecting on recent policy, “what I regret personally is to have felt bound by our forward guidance.”

Shifting PEPP reinvestment plans. Finally, and briefly, the initial commitment was to continue PEPP reinvestment through end-2024, repeated often since it was first made. But in December, the Governing Council reneged on this policy by announcing that the PEPP roll-off would begin mid-2024.

And we could add a number of other press conferences that wrong-footed investors into misunderstanding Lagarde’s intentions.

A common theme runs through these examples: confused messaging and policy flip flops.

Inconsistency of suboptimal plans

Of most relevance for asset prices is the apparent inability to commit to policy plans—the result being rapid readjustments and occasional retrospective changes to policy.

Why is this happening? An obvious place to look is the growing influence of the Governing Council on decision-making at the ECB.

Process matters. And as noted previously, Lagarde committed on appointment to democratise decision-making in favour of the Governing Council whose members apparently felt overlooked by Draghi. Previously, ECB staff—or a small, connected group—would be central to decision-making. Since Lagarde the out-sourcing of policy strategy to National Central Banks, and the inevitable political influence that follows, has had a greater influence on policy.

This inevitably means overlooking ECB staff more than previously. Lagarde is being pulled in more directions and cannot be as responsive to ECB staff as previous Presidents.

In turn, this finds expression through more volatile policy-making.

Of course, policy should be flexible and able to respond to new information.

At this point it is usual to trot out the standard Keynes quote for the occasion, this one being: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” Last month Schnabel delivered.

But the politicisation of decision-making in general finds its way into staff analysis who try not to deliver an objective reality but on their reading of the political landscape. This makes it more difficult to set policy on the basis of a sensible medium-term outlook.

Policy becomes prone to fear and fad—to knee-jerk decision-making, unable to commit to medium-term path, unsettling asset prices.

Not least, the inability to forecast the acceleration of inflation in recent years is now being met by a symmetric failure to grasp the inflation undershoot on way down.

What happened to the conservative central bankers?

Perhaps the greatest irony of modern central banking is the academic obsession with overcoming the political cycle alongside the role for the conservative central banker engaged in inflation forecast targeting.

Instead, central banking is often outsourced to recently-ousted politicians, especially in the Eurozone, or officials from the finance ministry, in the UK case, with poor analytical frameworks and shorter horizons.

One only needs to glance through the list of ECB Governing Council members and count the number of former finance ministers and politicians, including Lagarde, to realise how disconnected is reality from the academic ideal.

Of course, politician central bankers need not drive the cycle around elections. But it still makes policymaking prone to the whim of vainglorious deal-makers.

No remorse

In summary, investors need to acknowledge that policy has become more politically-driven and therefore less predictable.

Moreover, a key characteristic of Lagarde and her associates is the lack of introspection and unwillingness to acknowledge obvious failures. It’s always someone else’s fault.

Economists got the flack at Davos earlier this month when Lagarde called them a “tribal clique” implying they were to blame for flawed inflation projections.

Returning to the “spreads” remark in March 2020, a half-hearted recent mea culpa offered to the FT saw Lagarde insist the original statement was “technically true” before trailing off.

No real remorse here.

And so it should be no surprise that when challenged last week on the contents of the critical staff survey, Lagarde dismissed the findings. When asked what she would do to address the criticism she had no response except to claim that she is irrelevant. There was no suggestion she will engage with the substance of the survey.

When lessons are not learnt, mistakes will recur. This was also a feature of Lagarde’s period as Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund.

Meanwhile, the Governing Council has to perform yet another flip-flop. Policy was tightened far too aggressively in 2022-23 and the danger of undershooting the inflation target once more is beginning to grow. Perhaps forward guidance was a sensible policy after all.

*Lagarde told CNBC that “I am fully committed to avoid any fragmentation in a difficult moment for the euro area...”

The content in this piece is partly based on proprietary analysis that Exante Data does for institutional clients as part of its full macro strategy and flow analytics services. The content offered here differs significantly from Exante Data’s full service and is less technical as it aims to provide a more medium-term policy relevant perspective. The opinions and analytics expressed in this piece are those of the author alone and may not be those of Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC. The content of this piece and the opinions expressed herein are independent of any work Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC does and communicates to its clients.

Exante Advisors, LLC & Exante Data, Inc. Disclaimer

Exante Data delivers proprietary data and innovative analytics to investors globally. The vision of exante data is to improve markets strategy via new technologies. We provide reasoned answers to the most difficult markets questions, before the consensus.

This communication is provided for your informational purposes only. In making any investment decision, you must rely on your own examination of the securities and the terms of the offering. The contents of this communication does not constitute legal, tax, investment or other advice, or a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. Exante Advisors, LLC, Exante Data, Inc. and their affiliates (together, "Exante") do not warrant that information provided herein is correct, accurate, timely, error-free, or otherwise reliable. EXANTE HEREBY DISCLAIMS ANY WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.

None of this can be a surprise as she was always unfit to be ECB head. she is a politician, as you describe, and a crooked one at that. One should expect that there will be many more errors before her term is over.

Operative quote is the one on those with poor analytical frameworks. Lagarde lacks the conviction of a framework for analyzing what’s happening in the economy and how a CB should react to a set of economic developments. Hence, decision making has one eye on external factors; understandably, as ECB is meant to oversee monetary policy for a a disparate group of countries. But knowledge and conviction matter especially now that the ECB has to contend with the possibility of inflation resuming.