Mortgage interest payments and the policy cycle

Monetary tightening works faster when household mortgages reset quicker

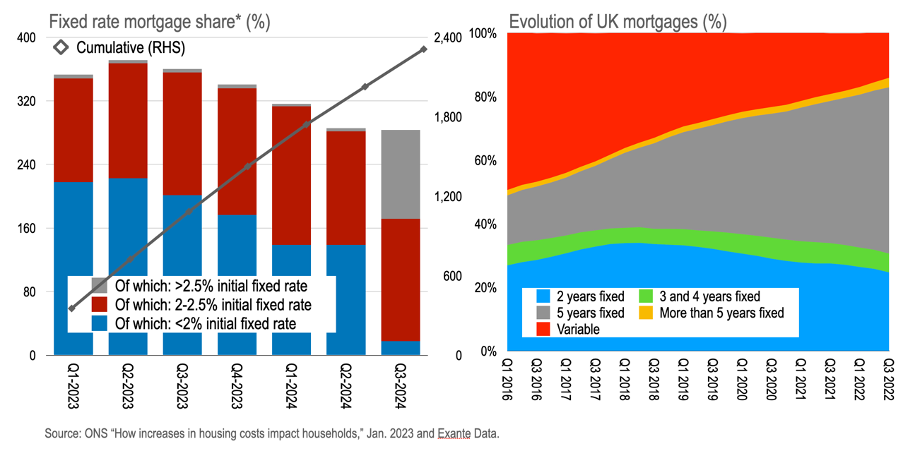

The average maturity of household debt differs across countries due to structural characteristics;

This is reflected in the share of fixed and flexible rate mortgages, for one. But the average maturity of fixed rate mortgages also differs—being only 5 years in the UK, for example, but about 30 years in the US;

Looking at household disposable income an alternative window onto mortgage interest payments historically—and the sensitivity of households to policy changes.

With rates normalising above pre-pandemic cyclical highs, the knock-on to floating rate mortgage holders is inevitable—or mortgages on fixed rates that need to be re-set in coming years. This in turn with have macroeconomic repercussions.

Indeed, the average maturity of fixed rate mortgages differ between countries (typically 5Y in the UK, vs 30Y in the US).

In the UK, according to the ONS, about 1.4 million fixed rate mortgages will re-set over the next 12 months while roughly the same number are floating. Only last month, the Bank of England warned that the number of households with a “high mortgage debt burden” is expected to reach levels this year not seen since GFC.

Through mortgages, policy tightening feeds only slowly into household disposable income and spending. This is a reason for caution in raising rates late in the cycle.

But this is a global theme, of course.

To understand the lags and impact on spending, we look here at the historical link from policy rates to disposable income within the national accounts for the US, Europe, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The caveats here being that the average fixed rate mortgage maturity has lengthened over time, so this likely marginally overstates the speed and end-point—while there are some data comparability challenges.