New Keynesian macro and inflation forecasting

The future "output gap" drives inflation in modern macro. This is a problem.

The New Keynesian (NK) macro model has become the workhorse for many central banks in making forecasts and setting policy. A comprehensive list of such models is provided in this excellent recent survey from Japan.

But the NK model remains largely a black box. It’s difficult to gain intuition as to what drives model outcomes—and how this therefore guides policy, particularly in the post-pandemic period.

To peer inside this black box, we walk through the intuition for a very simple version of the model (drawing on Gali). While imperfect, this simple exercise helps illuminate why forecasting is so tricky at this time.

In short, macro models have come to rely excessively on three unobserved (and unobservable) concepts: the expected output gap, expected inflation and the natural rate of interest. This creates blindspots in policymaking. They are all abstract, subject to uncertainty and measurement challenges, and none directly linked to macro indicators of aggregate spending decisions today—meaning central banks can end up driving with the rear view mirror, reacting to inflation outcomes rather than balance sheet developments and aggregate demand.

Escaping the liquidity trap

We begin before the pandemic, in a liquidity trap world: the natural rate is zero as are future inflation expectations. Monetary policy is committed not to respond to inflation immediately—so a simple Taylor Rule does not respond to inflation immediately.

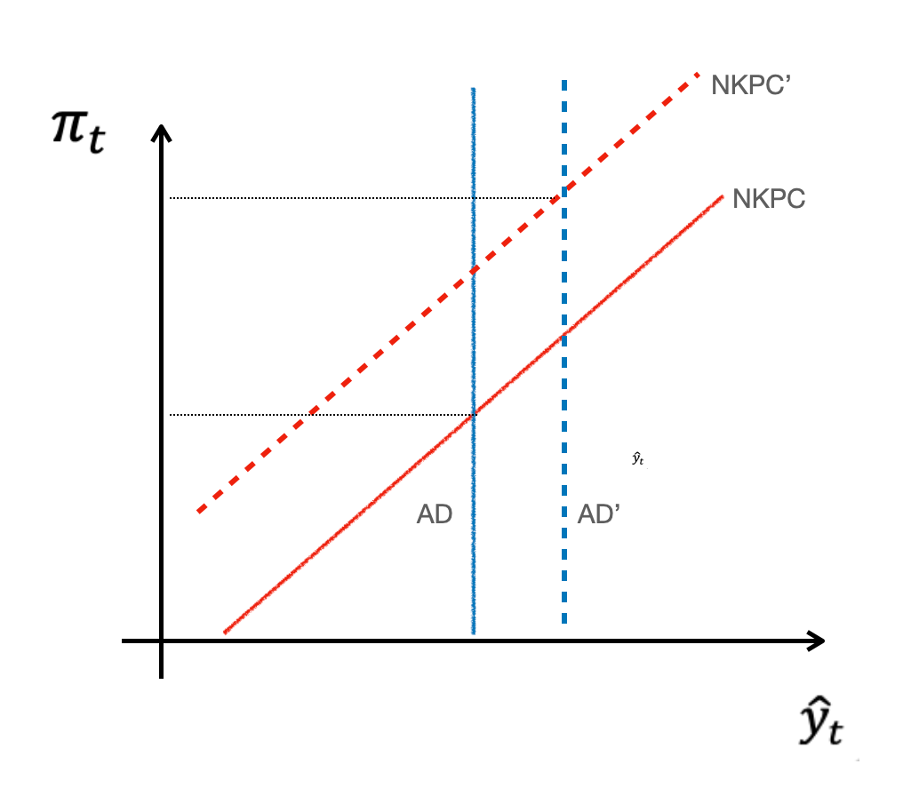

The NK model can be boiling down to a simple aggregate supply-aggregate demand diagram, as here:

How do we generate inflation in such a world?