The Great Confusion

Coordinated policy actions are (once again) missing at the IMF Spring Meetings

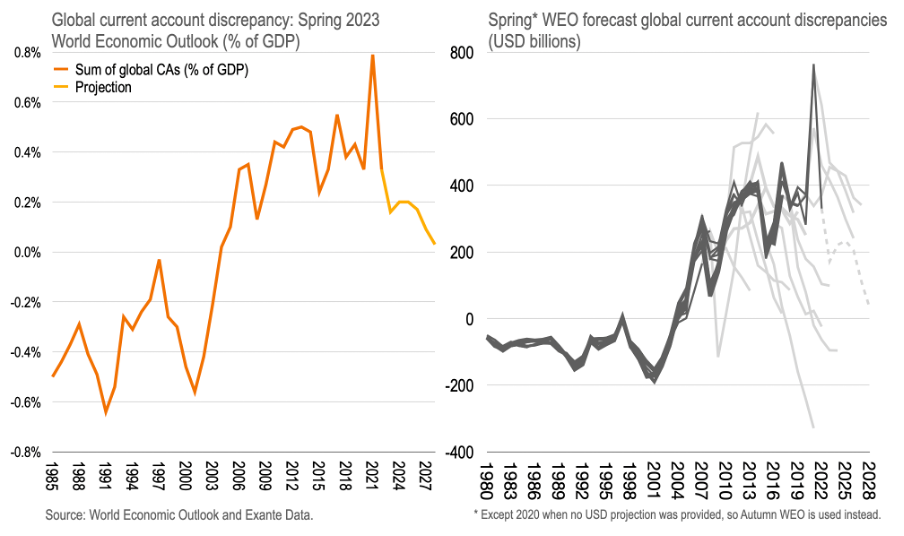

The latest WEO projection shows substantial global current account adjustments through 2028;

But the surplus countries (China and energy exporters) are expected to adjust more than the deficit countries—which nearly eliminates the global current account discrepancy by 2028;

This is since the WEO mainly aggregates individual country-team forecasts and doesn’t ask whether the global policy stance is appropriate; there is no meaningful coordination of global macro policies.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) Spring Meetings delivered the usual stream of headlines this week: deglobalization and shifting FDI could lower global growth; fiscal consolidation is needed to support disinflation and contain borrowing costs—despite the fact that the growth outlook is dimming; higher interest rates are a challenge for financial stability. But, still, interest rates will likely return to pre-pandemic norms—in which case, what’s all the fuss about?

Of course, such gatherings are intended to maximise publicity. They can therefore add to confusion rather than, as they ought, promote the coordination of policy.

But was there a hidden message from the global outlook?

Adjustment ahead

Beneath these headlines, though unremarked, were some notable features in the projected adjustment of the global current accounts over the remainder of the decade.

Take the global current account discrepancy.

Global current accounts, surpluses and deficits, ought to sum to zero. But they don’t due to various reporting errors. Traditionally, that is in the 1980s and 1990s, the world consistently ran a deficit against herself that moved around but averaged about 0.4% of GDP. It was thought this was largely due to the under-reporting of investment income by developed markets in particular. Suppose a multinational has an investment abroad on which they generate a return. If they understate this for tax purposes then the country in which they are resident will report lower credit items on the income balance—and so register a lower surplus or deficit. Hence the discrepancy.

Since the mid-2000s, however, the sum of current accounts for the world has reported a surplus of about 0.4% of GDP instead—flipping the sign of the global discrepancy. There has been no effort to explain this change, though it may be related to implementation of Balance of Payments Manual 6 reporting.

Moreover, this discrepancy jumped sharply in 2021, during the pandemic, to about USD750bn or 0.8% of GDP—a record high.

In any case, looking at the latest World Economic Outlook projection for the sum of global current accounts, we see this discrepancy falls to about 0.2% of GDP this year and is expected to fall further to near zero by 2028.

But the WEO has a legacy of producing global current account adjustments in either direction as it largely sums the individual country projections without forcing a globally consistent picture (right chart.)

It’s mostly energy (and China)

But why is the global current account surplus discrepancy expected to narrow? You won’t get an answer in the WEO text.

As noted, the global current account discrepancy is expected to adjust downward by about USD300bn over the next 6 years—with roughly one-third of this adjustment over the next two years.

A decomposition of the change in the projected current accounts from 2022 to 2024 and 2024 to 2028 for the 15 largest positive and negative (absolute) adjustments is shown in the table below. In GDP terms, these countries represent about 80% of the global economy.