The growing velocity of fractional securities settlement: an unintended consequence of QE?

The expansion of securities settlement that has accompanied QE is seldom remarked upon, but could be reshaping the financial landscape

Editorial comment: There has been much discussion of the impact of central bank QE through the usual portfolio balance and signaling channels. In this second guest post, Meyrick Chapman asks whether the increase in the velocity of securities settlement that has accompanied QE has received sufficient attention, and whether the traditional fractional reserve banking model is evolving into a “fractional securities settlement system”—to the benefit of the financial system but with little impact on monetary policy ends. The views in this Substack are not necessarily shared by Exante Data. But they might be. We like to hear a diverse set of global perspectives. Reach out to us on info@exantedata.com if you have a specific proposal that fits the format and topic of the blog.

Fiat money depends, to a very large extent, on its role as a liability of the state. The asset and liability relationship between private and public sectors that emerges from this relationship is the foundation of the payments system and, ultimately, the legitimacy of the currency itself. So, we should view with some concern the changes that central bank policies are having on fundamental aspects of this relationship. Indeed, the expansion of bank reserves held at central banks may alter our financial systems in ways that no-one has agreed to, or even, apparently, discussed. This expansion also may have important implications for the economy and society.

Fractional reserve banking and the velocity of money

Under the traditional fractional banking model, commercial banks held reserves at the central bank as a buffer and used their privileged access to central bank liquidity and their own assessment of their customers credit risk to create loans for existing or new businesses or households. This model has broadly held sway for a couple of centuries. At least till now.

As the assets of central banks expanded with QE, so did their liabilities; notably (though not exclusively) through the reserves held by commercial banks at the Central Bank. Most comment surrounding these changes has focussed on either: (1) the total size of the balance sheet or (2) the effects of central bank acquisition of assets, such as bonds. And certainly these are eye-catching. But it is the liability structure of central banks that has traditionally been of greater importance for a currency.

Commercial bank reserves, a liability of the central bank, together with notes and coins (currency in circulation) form the Monetary Base; so-called because it forms the base upon which fractional (commercial) banking is built. And from the fractional banking system all other forms of money and finance within an economy are built (term-lending, long-term savings, investment, shares, bonds).

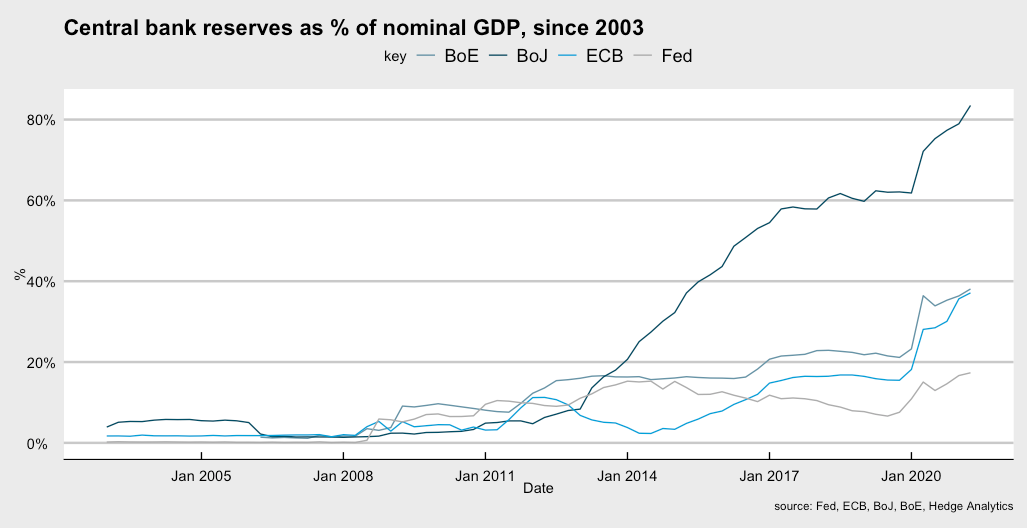

And bank reserves at major central banks have reached very high levels. Commercial bank reserves held at the Bank of Japan amount to over 80% of GDP. At the ECB and the BoE bank reserves account for nearly 40% of GDP while at the Fed reserves account for nearly 20% of GDP. These excess reserves of commercial banks held at the central bank are funded at term funding rates. And despite being about as risk-free as possible, they attract penalties in the United States due to Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) and other Basel regulations—though subject to review. It has never been clear reserves held at the central bank, which are the equivalent of cash in hand, should attract any penalty at all. But that is another story.

The velocity of securities settlement

Of particular interest here, however, is the link between growing central bank reserves and securities settlement.

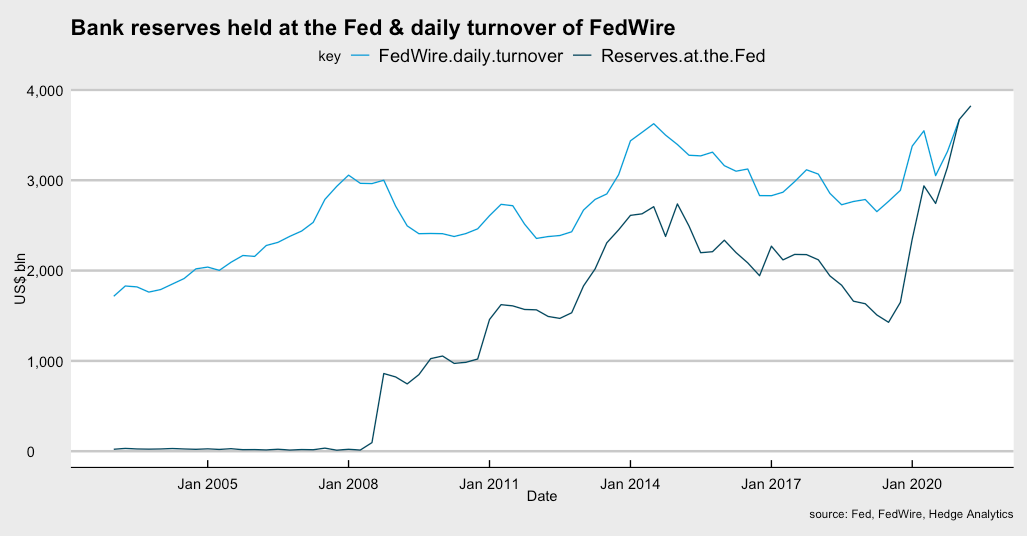

The charts below show the daily average turnover of FedWire (in the United States) and TARGET2/T2S (in the Eurozone) compared to the stock of bank reserves held at each central bank in outright currency terms.

As noted, as a growing proportion of commercial bank balance sheets, excess reserves at the central bank displace private sector loans and therefore credit creation for new ventures. But they also appear to be increasingly used to facilitate trading in securities markets, rather than credit creation for the wider economy. The chart below, for example, shows the daily turnover in the US FedWire system—the Fed’s settlement of financial transactions against bank reserves held at the Fed. The turnover of financial transactions has increased sharply in recent years and appears to be at least coincident with the increase in Fed reserves.

This development may be unintended. Yet given the apparent impact, it is strange that it has entirely escaped attention. It would seem important to discuss a central bank policy that appears to distort normal banking functions for the wider community yet supports securities transactions for commercial banks.

While presented as macroeconomic imperative, central bank policy represents an incursion into the general banking ecosystem. As a result of QE, an ever larger share of community assets and liabilities are directly held by, or against, the central bank. This is not unprecedented. In the early days of the Bank of England, the rudimentary nature of commercial banks allowed the Bank to take a high proportion of total banking activity. But we can hardly call today’s banking system ‘rudimentary.’

Of course, there may be other explanations, of which more shortly.

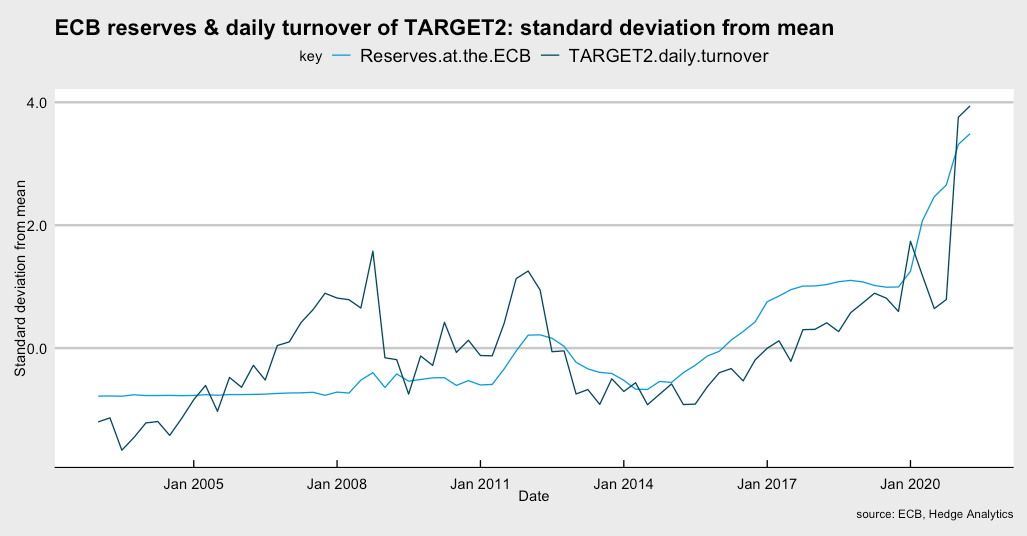

The increase in the use of central bank money as settlement for securities transactions can also be seen in the ECB’s RTGS (real-time gross settlement) system and T2S component of TARGET2.

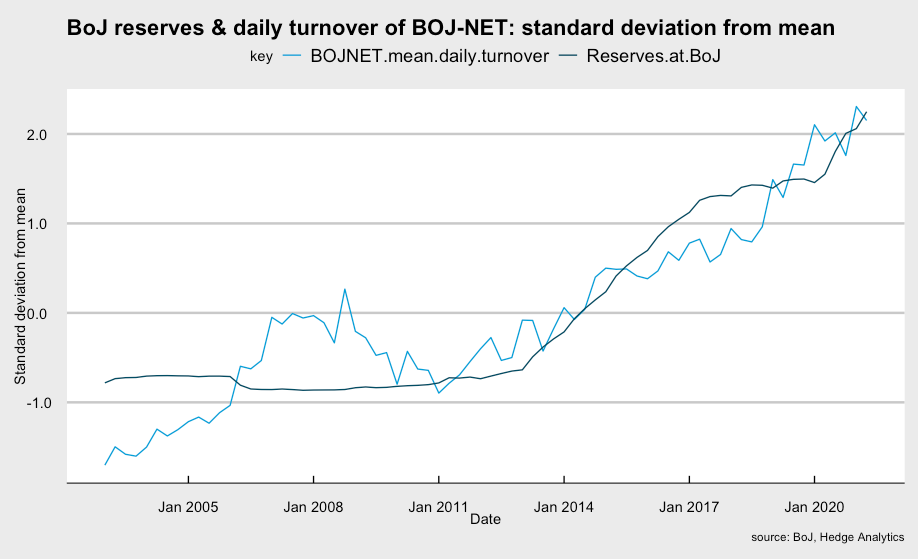

In both Europe and the US the daily turnover of both central bank payment systems equals the total stock of bank reserves held at the respective central bank. In other words, central bank money may be accounting for securities settlement equivalent to ~20% of GDP per day in the US and ~40% of GDP per day in the Eurozone. Similar analysis for the Bank of Japan reveals there has also been a rise in settlement via the BOJ-NET system as bank reserves held at the BoJ expanded.

Perhaps there is a straightforward answer to this phenomenon. QE entails the central bank buying bonds from private investors – a financial transaction. Those private sector investors then need to re-invest the cash they received from the central bank in other securities. Every QE transaction therefore creates at least two sets of transactions, which require ultimate settlement via the banking system. Unless those transactions are all settled at the same bank, a settlement between banks, using central bank money is required. That points to an obvious link between the amount of QE and the overall turnover of securities. Yet, the daily turnover of central bank money is so much higher than the daily dose of central bank asset purchases. This explanation seems inadequate to explain what is going on.

In short, the volume and value statistics for FedWire and TARGET2/T2S show velocity of central bank money with respect to financial transactions is staggeringly high. So high that it is worth asking if central bank money may have radically expanded the range of highly liquid securities, and therefore raised their value, while facilitating the churn of such securities. Again, perhaps this is intentional. But, this occurs only within the magic circle of those who can access ‘central bank money,’ and is not subject to public discussion by policy makers or scrutiny of lawmakers.

From fractional reserve banking to fractional securities settlement

And so, what was previously a ‘reserve’ held as a basis for fractional reserve banking and credit creation looks increasingly like the foundation for a ‘fractional securities system’ with enormous liquidity—but little obvious connection to the well-being of the wider population. While almost every citizen has an interest in a bank loan at some point in their lives (mortgages, loans for education, cars) not every citizen has an interest in facilitating securities transactions. Yet this appears to have been, perhaps, one of the main unintended consequences of central bank policy.

And there is another exclusionary angle to this development. Because facilitating securities transactions also helps raise their prices and aids trading, both are sources of profit for those with privileged access to central bank money.

There is, of course, the familiar route by which QE aids asset owners. Namely, through ‘portfolio rebalance’ which pays investors to move from low-risk bond markets into more risky investments, thereby raising the price of bond markets and riskier investments.

What is described here, however, may be another channel supportive of asset prices through bolstering liquidity via the central bank payment system. Higher the liquidity for a security invariably means higher value, as its worth can be readily translated into cash. The most highly liquid securities can therefore be thought of as a form of cash. Traditionally, such liquidity applied only to very short-dated government bills and a few other highly rated securities. No longer.

Conclusions

The point here is not to question the motivation for traditional asset purchases, but to question the possible unintended consequences of unconventional monetary policy—benefitting financial market participants, but hardly promoting intended monetary policy ends.

And these developments are unprecedented, at least as far as available data is concerned. They therefore give rise to a number of questions.

· What exactly is the mechanism that links QE and securities transactions?

· Why is daily turnover of central bank money so high and correlated with reserve money?

· What is the distribution of this turnover?

· Is it possible to estimate the impact that the increase in velocity of central bank money has had on the value of asset prices?

· Why is the central bank apparently willing, without discussion, to favour financial insiders, rather than society at large beyond the initial purchase impact?

· Or, if you prefer, how does the increase in transactions measured in the two payment systems in the United States and Eurozone contribute to wider economic wellbeing?

· And why is this novel aspect of modern monetary policy not discussed?

The possibility of rising inflation and its effect on the wider economy has received a great deal of attention. But with such high velocity evident in central bank money, it is possible that even relatively high inflation would have little impact on those transacting in securities markets, while those without such privileges may be adversely affected.

Appendix: Brief Biography for Meyrick Chapman

Meyrick is an investment industry professional with 40 years of experience focussed on macro-investing. For 11 years prior to end-2020 Meyrick was employed by Elliott Management, a multi-strategy asset manager with >USD40bn AUM. In that role, Meyrick traded in currencies, rates and bond across major developed and emerging markets. Prior roles include 12 years at UBS, becoming head of European Interest Rate research and 6 years as proprietary trader at Bankers Trust. He is Chairman and founder of the Market Structure group (under the umbrella of the European Policy Forum) which brings together major figures in European and US market regulation with European market participants to discuss structural effects of regulation on markets. Linked-in here. Twitter: @meyrickc.