The Norwegian Krone is becoming a “global” currency (Part I).

The Norwegian Oil Fund is the world's largest sovereign wealth fund. As the fund continues to grow rapidly, Norway and its currency (NOK) becomes more exposed to global finance than to oil prices.

The Oil Fund is now more than three times the the size of the Norwegian economy, and its growth will likely continue to exceed growth in Norway's nominal GDP growth. As such, the strength and weakness of the Norwegian Krone (NOK) should correlate more with global asset markets than Norway-specific fundamentals, including the oil price. In short, the NOK will increasingly become a play on global asset price developments and the importance of the Fund’s asset allocation decisions for global assets will continue to grow. This also means that macroeconomic policy management will be facing highly unusual challenges.

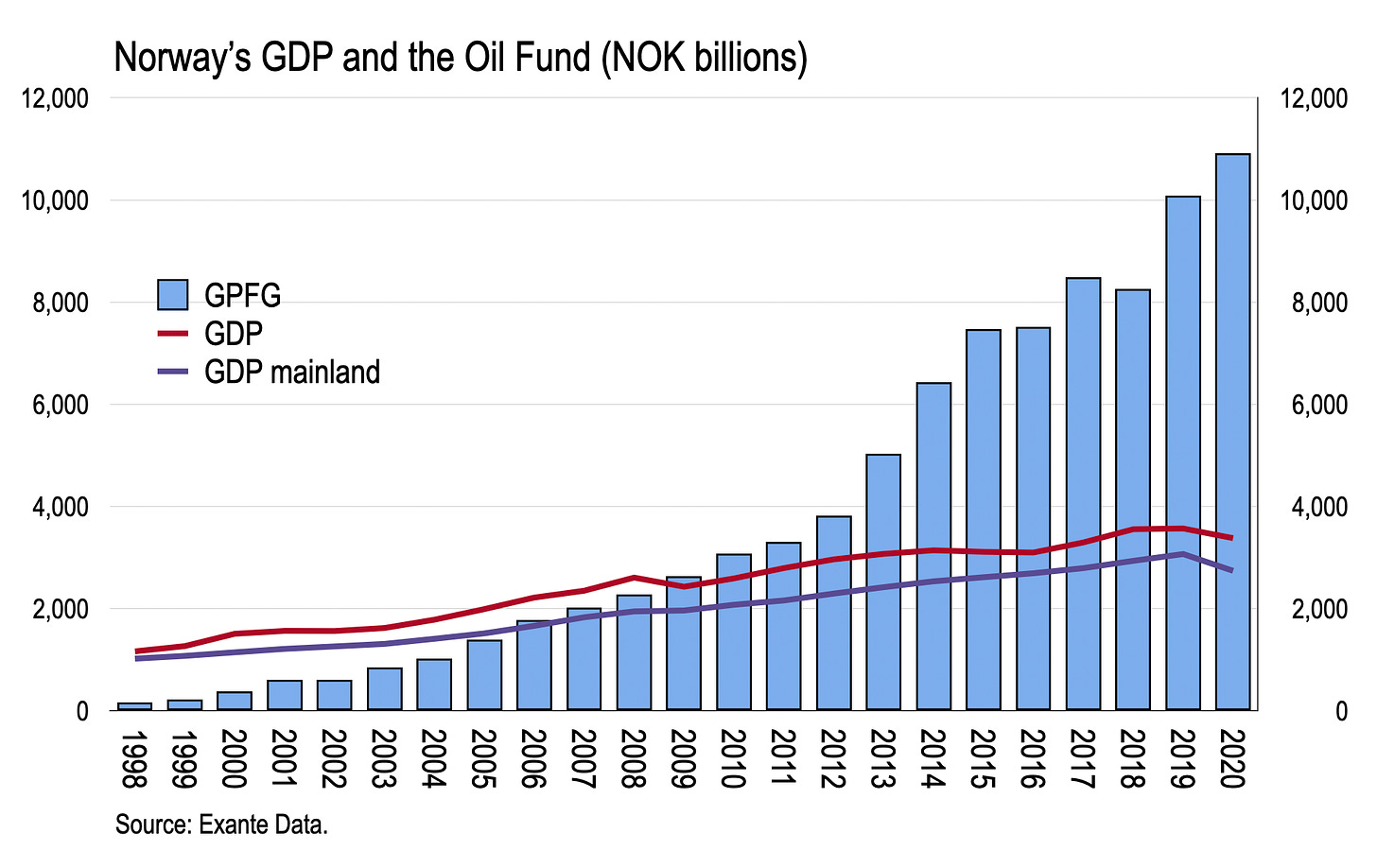

The Norwegian State Oil Fund (formally called Government Pension Fund Global) has quietly grown in size relative to both the Norwegian economy and as a player in global financial markets. Only fourteen years ago, the size of the Oil Fund surpassed Norway’s mainland GDP and three years later overall GDP. Today, the oil fund is 325% of annual GDP. In global terms and in nominal value, the oil fund is huge.

To put some perspective on its size:

It is as if every Norwegian has a personal offshore investment portfolio of USD240,000;

The Oil Fund owns >1½ percent of all listed shares in the world;

The return on investments for the Oil Fund just in 2020 was equal to 32% of GDP – and that was in the year of the pandemic;

This return on investment was roughly the amount paid in salaries to all working Norwegians.

This is a unique position compared to any country in the world, including those who have been oil producers longer than Norway. Historically, such dominance in overseas investment is usually associated with reserve currency issuers, such as for GBP during the UK’s role in the 19th Century, and USD in the post-war period.

The trend has much further to run

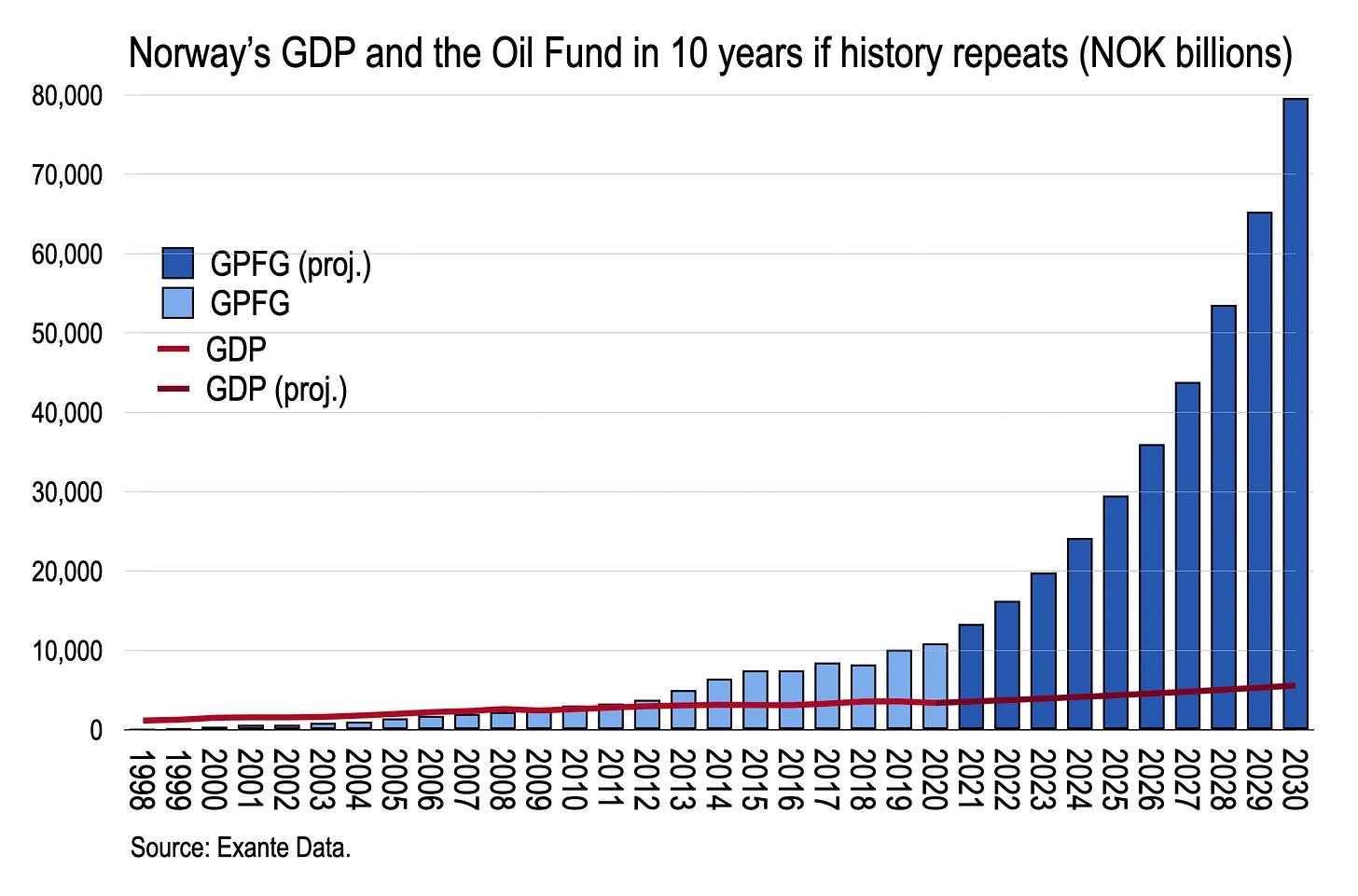

Imagine a scenario where the world, as seen over the past 20 years, repeats itself in economic terms. The Oil Fund grows at the same annual rate as it has historically, as does Norway’s GDP. If so: GDP will be 65% larger; the Oil Fund 630%. Alternatively, the Oil Fund will be 14 times larger than GDP, compared to about 3 times today.

Now, some caution is needed in this thought experiment. The oil price might not reach $100 per barrel, as seen for many of the years during the last 20 years. Interest rates were higher, and equities had lengthy good periods.

So, let’s be conservative and have both the Oil Fund and the GDP grow at half the average rates seen throughout the last 20 years. In that case, the Oil Fund is still going to be 7 times bigger than GDP.

The main message here is that value creation for Norwegians over the next decade will most likely come more from the development of their Oil Fund than from their own domestic economic activity.

Fair Value: The Special Case of the NOK

Most fair value models for currencies are driven by standard macro variables: Inflation, productivity, terms-of-trade, external balance. And then there is a set of reasons why current market values are different from those set as fair.

For the NOK, the gap between what was generally seen as its fair value and the currency’s rather volatile price fluctuations could be explained by several factors over the last 7-8 years:

The oil price and its importance to economic activities in Norway, as oil tax revenues are used to pay for investments and exploration, make up budget balances with the remainder put into the Oil Fund;

In the lower interest rate scenario throughout the last 7 years, the NOK gradually lost its interest rate premium, which made it more equal to other currencies and cheap in terms of funding cost for short positions;

Being classified as a high-risk asset class, it was sold off whenever the risk outlook deteriorated and bought back again when risk sentiment improved;

The NOK market is small and price action often reflects thin liquidity;

A few market participants are highly influential to price action.

Most analysis of the NOK follows standard macro thematic thinking, with a focus on the Norwegian economy, Norges Bank, the oil price, and a bit about impact from the country having an open economy. Risk sentiment is often used as the reason for moves not being explained by the factors above. But as the Oil Fund grows, with exposure to only international assets, Norwegian fundamentals will be increasingly less relevant to Norway’s currency. The Norwegian Krone will increasingly be a barometer of global growth and asset performance.

Fair value: The future framework

The NOK’s weakness over the last 7 years has added substantial value to the Oil Fund as it is accounted for in the local currency. This weakness is often linked to global risk sentiment. And whenever the Oil Fund’s underlying assets dropped in value, NOK weakness deriving from it, would compensate for these losses measured in local currency.

An implication of this is that, given the growing importance of the Oil Fund for the Norwegian economy, fair value for the NOK should increasingly be set based on developments in the global economy and the global outlook:

Focus should be on the outlook for global markets – all of them, as the Oil Fund is and will be invested everywhere, in equities 70%, fixed income 25%, commercial properties 5%;

More weight should be put to the currency’s USD dependence, in 2019: 40% and growing;

Some attention is justified in terms of putting weight to what is happening in the Norwegian economy as the economy is still 1/3 of the size of the Oil Fund - but - by the time it will be 1/6 or 1/12 – few should have worries about what the Norwegians will be doing back home;

To this point, we might add whatever Norges Bank will be doing in terms of monetary policy.

Global dependence via the Oil Fund means volatility will likely still be significant for the NOK and cause substantial price swings. To the bottom of that is liquidity – or rather the lack thereof – which ought to be a priority for Norges Bank. One option, for example, would be for the Ministry of Finance to borrow money instead of tapping the Oil Fund to pay for public deficits—to improve liquidity in the NOK market. A solid bond market supports currency fundamentals.

Regardless, the future for the Norwegian economy risks becoming one where global asset prices drive the NOK and, in turn, domestic inflation and - potentially - deflation. It may be that Norges Bank is a bystander, unable to control domestic inflation as the currency becomes a hedge for global financial market outcomes.

The Oil Fund is the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world, and it is hard not to view that as a good thing, from the perspective of Norwegian citizens (which implicitly hold incredible external wealth via the fund). But the huge size of the fund also means that macroeconomic management is challenged, and the Norwegian Krone in particular may start to behave in way that is increasingly divorced from domestic fundamentals.

A final point...

It is a strange artefact of history that the Oil Fund was structured as a foreign exchange investment portfolio, not to contain NOK assets. Yet the fund is reported in local currency terms. As such, a lot of value has been generated for the Oil Fund from an asset class, the NOK, which was not supposed to be part of the fund.