To catch a falling knife: US Treasuries and the Fed (Part 1)

Saving-investment balances in the great reflation

Shortly after the Federal Reserve System was formed in 1913, the Great War interrupted the emergence in the United States of monetary arrangements intended to mimic those enjoyed back in the Old World. Rather than the expected focus on furnishing an “elastic currency” that might eliminate bank runs, by early 1917 it was the absorption of Liberty Bonds to finance the war effort that came to dominate both monetary and fiscal policy discussions.

To this end, a plan was evolved roughly as follows:*

· First, cash for the war effort was raised by Treasury bill issuance, absorbed initially by banks simply registering offsetting deposit liabilities. Treasury deposits were not then, as now, concentrated at the Federal Reserve System meaning there was no immediate draw on bank liquidity; with these deposits also not subject to reserve requirements, this was purely accounting.

· Second, when Treasury called upon these deposits, bank reserves were drawn down but they “tried to minimise such effects by paying out these funds immediately and in the same district where these deposits were located” so liquidity remained evenly distributed across the System.

· Third, the money supply that emerged as the counterpart to government deficits required a growing reserve base, so a preferential discount mechanism of 3% on 15-day notes was introduced for banks to create reserves across the Federal Reserve System—a rate favourable compared to the 3½% on Liberty Bonds so banks would not be penalised for financing the war.

· Fourth, the (initial) 3½% rate on Liberty Bonds was itself chosen by Secretary McAdoo below the prevailing market rate to avoid drawing funds away from other uses, to prevent financial disturbance through sharp portfolio shifts.

· Finally, these less frequent Liberty Bond issues would retire maturing Bills, ideally removing from banks the task of intermediating private savings and thus moderating monetary expansion. Indeed, “liquidation of the bond portfolios of the commercial banks was one index the Treasury used in the postwar period to judge the success of its anti-inflation strategy”—the link between money supply and price level being then sacrosanct in the minds of policymakers.

This is a caricature, of course. It was less a “plan,” more a series of improvisations. But it serves as a reminder that financial plumbing and superstructure considerations have always been central to policy considerations in the United States—and the distinction between monetary and fiscal policy often a subtle one.

Plus ça change

In recent weeks, global financial market participants have become transfixed once more by the US Treasury market and financial plumbing matters as various fundamental and technical factors interact, bringing the Fed and Treasury actions into sharp focus.

In terms of fundamentals, growing reflation expectations on vaccine progress together with President Biden’s aggressive fiscal plans imply substantial Treasury issuance at a time when the private sector is itself attempting to move into deficit. In addition, the Fed’s average inflation targeting (AIT) framework implies monetary policy is willing to see through an acceleration in inflation—but for how long?

On the technical front, at least three factors are in play: the drawdown of Treasury deposits at the Fed (the Treasury General Account, TGA); a relative decline in Treasury Bills outstanding in favour of coupon issuance; and the expiry of relief in banks’ Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) calculations of reserve and Treasury holdings. These technicals will make the intermediation of private saving in 2021 potentially very different to that experienced last year, as we discuss.

These then are the key issues weighing on the US Treasury yield curve and contributing to nervousness at key debt auctions this year, including again in the most recent 7-year auction on March 25.

The early guardians of the Federal Reserve System would in today’s challenges hear echoes of the mobilisation of finance for war with which they struggled over a century ago. But today, the United States dollar is the world’s reserve currency; all financial assets are priced in relation to the USD21 trillion-and-growing float of US Treasuries. And financial plumbing fixes in the US become equivalent to redirecting the pipes that link disparate economies to the global financial system.

How should we think about the unique monetary-fiscal configuration in the United States today? It’s useful to begin at a high level—with saving-investment balances, and how they will be reconciled as society emerges from the pandemic. Part 2 of this series looks will at the increase in duration issuance and financial plumbing concerns.

Saving-investment balances and the Great Reflation

There is indeed something remarkable about the macroeconomic policy unfolding in the United States today, although all the scare-talk of inflation risk often distracts from a deeper understanding of the forces at play.

Contrast fiscal policy this year with other recent interventions.

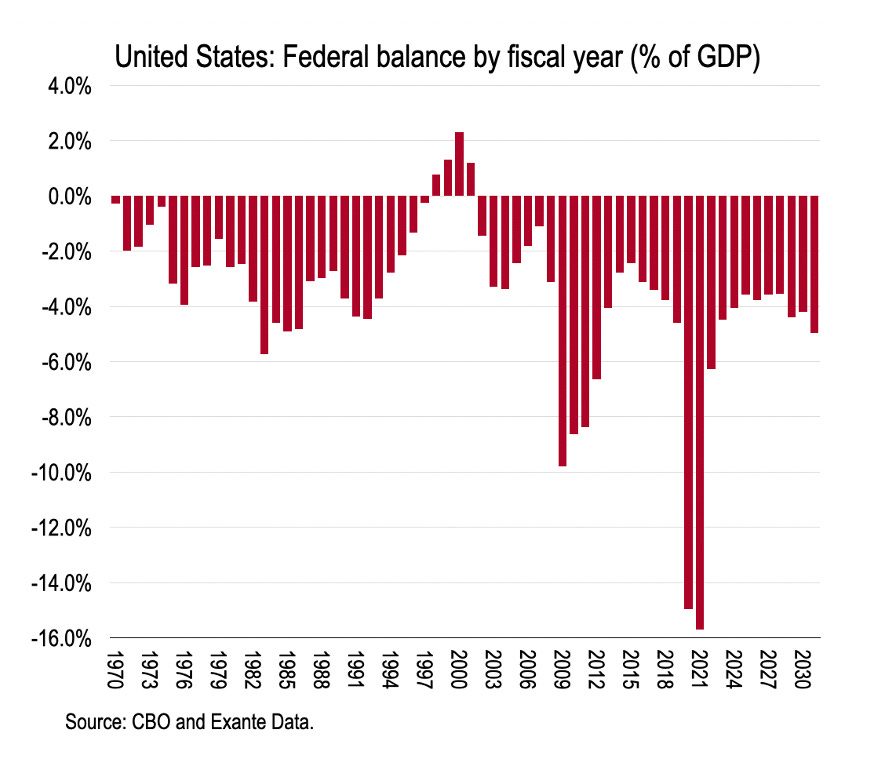

In 2009, the first full year after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), the United States Federal government deficit approached 10 percent of GDP; falling to about 4 percent in 2013. The cumulative Federal deficit over 2009-14 was about 40 percent of GDP and larger still if you count state and local government. Such post-GFC deficits were the necessary counterpart to private sector deleveraging as the housing boom reversed and households were left with bruised balance sheets. The fiscal deficit helped replace lost demand and help keep activity close to potential.

The logic of fiscal support last year, as the pandemic emerged, was likewise easy to motivate. The fiscal deficit in FY2020 was about 15 percent of GDP, or about USD3.1 trillion. This was necessary to replace lost private incomes while activity was artificially suppressed by lockdowns—in effect, the government was able to intermediate the savings of those who could “work from home” towards those whose incomes rely on face-to-face interaction and were otherwise badly impaired.

Both these interventions—post-GFC and during the pandemic—were aimed at recycling a naturally occurring private saving surplus—to replace lost demand and lost incomes.

In the year ahead, however, the fiscal deficit in the United States is set to remain very elevated despite an acceleration in private sector consumption and investment as the vaccines bring the lockdown to an end (alternative data already point to a sharp shift in demand in March).

How large will the Federal deficit be? The CBO baseline for calendar year 2021 already roughly pencilled in a USD1.9 trillion deficit, concentrated in the first half of the year. But this was before the Biden Plan which is itself (coincidentally) USD1.9 trillion (of which about USD1.3 trillion will likely be spent this year). As such, this year’s Federal deficit could reach USD3.2 trillion, only a whisker below the outcome in CY2020 (although we should note for good order that the stimulus will likely also generate some additional revenue).

When measured in terms of the fiscal year, the deficit in FY2021 (2020Q4-2021Q3) will slightly exceed that in FY2020—as shown in the chart below—while both will greatly exceed the deficits during GFC. And this does not even factor in the $3 trillion infrastructure spending which is now being planned.

Of course, this deficit will still be financed—the questions is at what price and by whom. Every monetary transaction is two-sided; each deficit must be offset by a surplus elsewhere.

This recalls the Swedish macroeconomic tradition from the 1930s which emphasised that ex post spending plans are reconciled through the monetary system even if ex ante plans do not mesh. Today’s anticipated deficit plans of both the private and public sectors in the United States have to be reconciled through a combination of (i) a wider external deficit—absorbing imports and dragging in external financing; (ii) higher corporate profits, wages and employment; (iii) greater-than-anticipated tax revenues; (iv) the rationing of supply—restaurants will be full; and (iv) inflation to bring nominal spending in line with real resources.

As such, and as usual, the US fiscal deficit will still be met largely by domestic private saving. Disposable income of the economy will adjust upwards, and planned spending down, to generate the private saving surplus to mirror the Federal deficit in 2021—despite ex ante plans. In the process, and even if the Federal deficit might come in somewhat below forecast as tax revenues accelerate, and though the current account deficit will itself likely increase sharply, private agents will find that—despite, or because of, their collective attempt to spend—aggregate income is greater than anticipated and they still have a surplus of saving to deploy!

Consider the sector balances approach. If the US current account deficit indeed touches 5% of GDP in 2021, even if the Federal deficit only reaches 12% of GDP, the private sector saving-investment balance in the US will by definition reach 7% of GDP. What is unknown is the precise mechanism bringing these balances into line, and precisely who among private economic actors ends up with the direct or indirect claim on the government that will emerge as a result.

But it seems likely that with corporates facing negative rates on deposits and growing charges for deposit services at banks, they may choose to return their surplus to households through (somewhat) higher wages as well as share buybacks or dividends to shareholders. So the key domestic surplus sector will once again be households, meaning household net worth will continue to improve in 2021 after reaching above 6 times nominal GDP in 2020 for the first time (though this metric hides important distributional concerns).

And stronger household balance sheets indeed have the potential to support a strong multi-year recovery, assuming the virus can be kept at bay. This does not directly imply unacceptable inflation pressure, however. Instead it will more likely bring other problems, including a wider current account deficit, growing asset price inflation, and greater inequality in the distribution of wealth.

Probably more important than worrying about inflation at this time is managing the structure of the consolidated government balance sheet during the recovery. The goal should be to avoid letting market technicals and financial plumbing concerns dominate macro-fundamentals in the pricing of key financial assets. If this were to happen, it could cause asset price volatility and provoke an adverse policy response.

We therefore turn next to how Federal government financing is changing this year, and how this interacts with financial plumbing issues. Look out for Part 2.

* This account, including the quotes, draws heavily on Elmus Wicker, Federal Reserve Monetary Policy, 1917-33; Random House, 1966.