What happened to the Taylor Rule?

Taylor's Rule and variants have largely been forgotten. But why?

Monetary policy rules were once a popular guide to policy setting—or a capsule summary of the practice of central banking;

If they were applied today in the United States, what would they imply for the current setting of policy?

Or, if they will no longer be used after the pandemic, what is there today to guide policy and markets?

Last week, Olivier Blanchard of the Peterson Institution for International Economics (PIIE) lamented the risk of accelerating inflation by pointing to the fact that Core CPI inflation in the United States has accelerated while the “real rate”—measured by the fed funds rate minus this inflation rate—is at a low last seen only in the early-1970s.

Blanchard’s chart is reproduced below.

At minus 6% the real rate looks perilously close to recalling the experience in the mid-1970s. It’s natural to wonder if we will repeat the mistakes then; Blanchard suggests we might.

What happened to the Taylor Rule?

There is another way of making this same observation: what happened to the Taylor Rule and associated Principle?

Monetary policy rules became popular in the 1990s and implied policy could be put on auto-pilot, responding mechanically to deviations of inflation from target and output from potential—or, put another way, a simple rule provided a capsule summary of complex policy decisions.

Such rules were popular until the zero lower bound (ZLB) became a constraint during the Great Financial Crisis (GFC)—after which balance sheet management and forward guidance, with the odd foray into negative rates, has come to dominate.

These rules embedded the Taylor Principle—or the idea that the policy rate should increase by more than the deviation of inflation from target, and the real interest rate should rise with building inflation.

And if the Taylor Principle had been in play over the past 12 months, the fed funds rate would have been considerably higher—and the negative real rate would have been somewhat offset.

In other words, perhaps Blanchard is really lamenting the demise of such policy rules and the strict adherence of policy to the Taylor Principle—as shown in the first chart above.

Indeed, what if such rules were in play today? What would they suggest of policy if applied throughout the pandemic?

A counterfactual

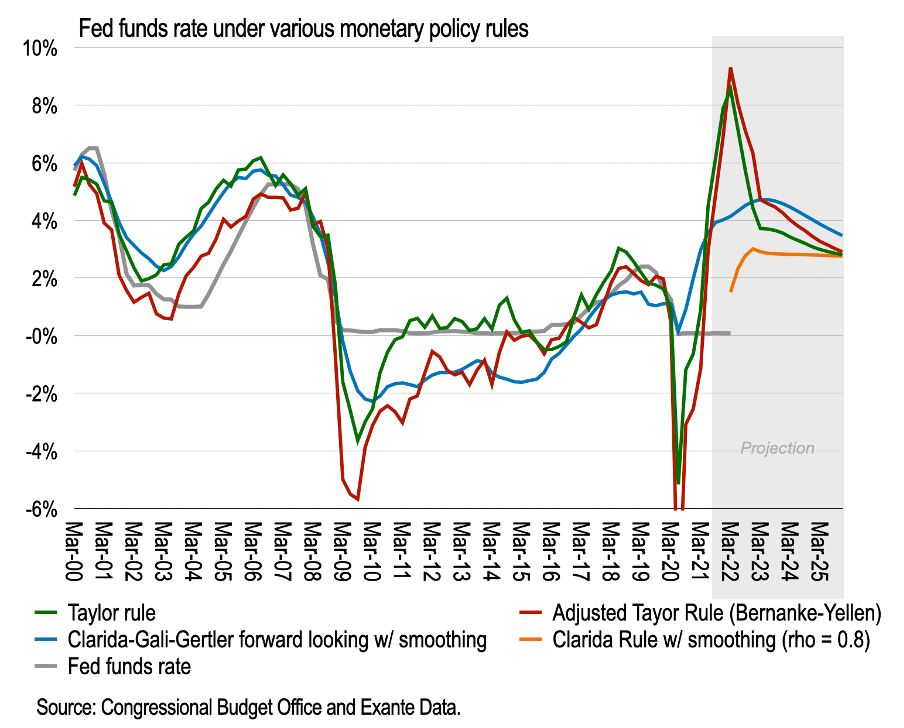

The first chart above (also summarised below) suggests where the fed funds rate (ffr) would be if some popular variants of monetary policy rules were deployed throughout the pandemic (the Annex provides sources and briefly describes these rules; we assume Clarida’s recently promulgated rule begins only this quarter.)

Obviously the lower bound on ffr means these rules could not be achieved during the pandemic when output gaps were understood to be large and negative. Hence the balance sheet expansion in 2020 as well as from 2009 onwards. But as of early-2021 these rules began to signal the need for a tightening of policy.

In terms of particular rules:

The traditional Taylor Rule suggests ffr should have been first increased in 2021Q1, to reach 90bps, while in 2022Q1 it should already be set at 850bps, declining to about 300bps by end-2025;

The Bernanke-Yellen adjusted Taylor Rule, which places a larger weight on the output gap, suggests ffr should have hit 300bps in 2021Q2 and should reach 930bp this quarter (given the higher weight on a positive output gap) but then also sharply adjusting lower;

The Clarida-Gali-Gertler (CGG) forward-looking rule currently points to ffr at about 415bps increasing to 470bps in 12 months before rolling off ;

Finally, Clarida’s recently promulgated rule, suggests an immediate increase in FFR to 150bps and to 300bps by end-2022 before falling to 275bps as of end-2025—roughly in line with the terminal rate from the first two rules.

The Taylor Rule and it’s variant due to Bernanke-Yellen, which do not deploy a smoothing parameter and react to contemporary deviations of inflation and output from target, imply a much more aggressive policy rate today.

The CGG and Clarida rules both employ a smoothing parameter (which we set it to 0.8, being the weight on lagged policy rate), such that ffr adjusts only slowly; the Clarida rule also puts no weight on the output gap and we assume this rule is only deployed from this quarter—making this slower to react still.

In other words, such monetary policy rules as were popular until GFC suggest policy has been too slow to lift off, by 3 to 4 quarters, and remains today a long way behind any sensible calibration based past experience—by at least 100bps, but in the case of the traditional Taylor Rule several hundred basis points.

Whither policy rules?

While informative, there may be reasons why mechanical use of such rules should be treated with caution still. Here are five.

Forward guidance. The first reason is simply that our current predicament of accelerating inflation is exactly what the doctor ordered. For years the danger was being stuck at the zero lower bound for a protracted period, hence academic disquisitions on policies to escape the ZLB and the subsequent commitment to flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT) at the Fed and the ECB’s forward guidance. The whole point is to show a willingness to allow inflation expectations to increase. To abandon such rules early would lose an opportunity.

Expectations remain anchored. In any case, second, the purpose of such commitment to overshoot was to raise inflation expectations—and since inflation expectations, while increasing, remain consistent with various definitions of price stability there is no need to rush to remove forward guidance. (For now.)

Output gap. A third reason is that the above calculations relies the output gap in the United States being positive at this time. The CBO projection on which these rules are derived has the output gap in the United States in 2022 above 2% while the latest IMF World Economic Outlook has the US output gap this year at +3.3%, the highest since estimates began in 1980. And yet real GDP has yet to return to the pre-pandemic trend. In what sense then can the economy be said to be overheating? Presumably, the switch in demand from non-traded to traded goods has brought some pockets of capacity shortfalls—and therefore relative price adjustment. But in the aggregate, is there a positive output gap? Well, maybe—due to skill mismatches and a fall in the labour supply. But output gap measures are fraught with guesswork—and it’s more likely that official bodies are showing positive output gaps because there is inflation rather than any meaningful assessment of potential.

Stocks versus flows. Fourth, such rules might have been a good description of policy-setting during the first decade of this century, but they overlooked then the macro-financial imbalances and housing market bubble that ended in the financial crisis. Hence Larry Summer’s secular stagnation speech in 2013 reflecting on the decade pre-GFC:

Everybody agrees that there was a vast amount of imprudent lending going on. Almost everybody believes that wealth, as it was experienced by households, was in excess of its reality: too much easy money, too much borrowing, too much wealth. Was there a great boom? Capacity utilization wasn’t under any great pressure. Unemployment wasn’t at any remarkably low level. Inflation was entirely quiescent. So, somehow, even a great bubble wasn’t enough to produce any excess in aggregate demand.

Household wealth. Finally, these rules fail to acknowledge that this cycle is different. As noted previously (here and here) household net worth during the pandemic surged by the largest amount (relative to GDP) in the postwar period—and while not evenly distributed, there was enough to go around so that even lower income households enjoyed an improved financial position.

This makes the current business cycle unique in that private balance sheets are at their strongest at the very beginning of the cycle—rather than themselves being the byproduct of other macroeconomic objectives.

Likewise, it is unique to witness the reduction in the labour force during and since the pandemic—workers who are only slowly returning to work, suggestive of a change in household labour-leisure trade-off either due to the pandemic itself or the associated policy response and household wealth effect.

Moreover, it is notable that a simple monetarist view on inflation—that is, focussing only on a narrow subset of household wealth in monetary form—predicts an acceleration in the price level at this time as all other prices in the economy adjust. By this view, such an upward adjustment in prices is inevitable. But it does not imply persistently higher inflation rate, unless the financial system were sufficiently elastic, and demand for credit sufficiently robust, to generate a permanently higher future growth rate in the money stock, spending, and rising prices.

Notice how the first three reasons to overlook these rules imply no reason to hurry back to their use. The latter two are more nuanced. After all, the size of the pandemic policy response was so large that it will take many years to wash out, and this is now coupled with a genuine energy supply shock due to the Ukraine invasion. Central banks will find it difficult to explain their failure to react if inflation overshoots various definitions of price stability. It’s ok to overshoot on inflation for a bit. But only a bit. And invoking stable expectations can only go so far. The mandate is price stability as suitably defined, not the stability of inflation expectations.

Conclusion: what next for policy and policy rules?

In reality, every generation is forced to rethink their understanding of, and approach to, monetary-fiscal management as the structure of the economy and the financial system changes—not to mention under the the sway of new thinking and external events.

We might be at another watershed in monetary history where previous simple monetary policy rules cannot just be dusted off and reapplied.

Indeed, it feels like policy is today grasping again to understand what is happening and how exactly to react. The beauty of previous rules is that they provided some guide. Today we have none.

But should we return to simple policy rules again? If so, at what pace? If not, what should replace them?

Policymakers ought to be aggressive in staking out a position on such questions to explain their strategy for macroeconomic management after the pandemic. Monetary policymakers in particular should provide clarity on their reaction function, including the role of central bank balance sheet contraction and their thinking on how they will react to robust private balance sheets.

Failure to provide such clarity risks complicating the formation of prices in real goods and services—not to mention financial markets trying to price the yield curve and an array of associated financial products.

ANNEX

Output gap and inflation

Before we can ponder what the Taylor Rule and its ilk would recommend for policy, we need the ingredients. Fortunately there are really only two inputs—the output gap and Core inflation (here we switch to PCE and GDP deflator.)

The chart below shows the historical and projected output gap and inflation using Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts from July 2021 modified as follows: we take their output gap projections as given, but update inflation for the end-2021 overshoot relative to their projection then. The baseline shows inflation returning to about 2%YoY in 2024 (their baseline), while we have a high-inflation scenario where inflation instead settles at 3%YoY.

Note, the CBO projection has the output gap in the United States in 2022 touching above 2% of potential before falling off to near target at the end of the forecast horizon. This is the largest positive output gap since the millennium.

As a cross-check, note that the IMF had the US output gap in 2022 at 3.3% (World Economic outlook, October 2021) the highest since their output gap estimate began in 1980.

In other words, an emerging consensus has it that the United States economy is running ahead of capacity—something that has not happened for at least 2 decades—despite employment yet to return to pre-pandemic levels.

Policy rules

We briefly recall four popular monetary policy rules.

Traditional Taylor Rule (Taylor, 1993)

The traditional Taylor Rule, introduced by John Taylor in 1993, posited a simple relation between ffr, the equilibrium real rate (often called r*), the deviation of the inflation rate (measured by the GDP deflator) from target and the output gap.

Crucially, the weight on the deviation of inflation from target received a coefficient of 1.5 reflecting the “Taylor Principle” that when inflation rises above target the real interest rate should be increased more than one-for-one. For Taylor, the weight on the output gap was 0.5.

With output at potential and inflation on target, ffr minus inflation will equal r* which Taylor pencilled in at the time at 2% but subject of much discussion since.

Modified Taylor Rule (Bernanke, 2015)

Ben Bernanke, writing at Brookings, offered a modification to Taylor’s Rule, drawing on work by Janet Yellen, to more realistically capture the FOMC policy process. Notably this rule “measures inflation using the core PCE deflator and assumes that the weight on the output gap is 1.0 rather than 0.5.”

Forward-looking rule with smoothing (Clarida, Gali, and Gertler, 2000)

Monetary policy is forward-looking. And in the late 1990s, former Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida—prior to his time at the Fed—along with co-authors estimated a forward-looking policy rule for various monetary regimes in the United States. These regimes were the Pre-Volcker and the Volcker-Greenspan periods, estimating different parameters for policy setting in each case. In the latter period, the Taylor Principle was adhered to—unlike the Pre-Volcker experience which Blanchard is concerned we will repeat.

They also allowed for only partial adjustment towards target based on an interest rate smoothing equation.

In short, using the parameters from the Volcker-Greenspan period estimated by CGG, the smoothing parameter was about 0.8 (that is, policy adjusts only slowly; the weight on the previous policy setting is 80% of the input to policy today), while the weight on the output gap is about 0.9, while the weight on the deviation of expected core PCE from target was about 2 (the Taylor Principle once more.)

Vice-Chair Clarida’s preferred formulation (Clarida, 2021)

Finally, while he was still Vice Chair Clarida explicitly endorsed an alternative policy rule once the conditions for lift-off are in place. In November 2020, for example, Clarida endorsed (emphasis added):

an inertial Taylor-type rule with a coefficient of zero on the unemployment gap, a coefficient of 1.5 on the gap between core PCE inflation and the 2 percent longer-run goal, and a neutral real policy rate equal to my SEP projection of long-run r*. [while] the degree of inertia in the benchmark rule I consult will depend on initial conditions at the time of lift-off, especially the reading of the staff's CIE [Common Inflation Expectations] index relative to its February 2020 level.

This is a mouthful. But basically, this is a variation on the CGG rule but with no weight on the output gap (i.e., unemployment gap) and lower weight on the deviation of (contemporary) core PCE from target.

Scenarios

Scenarios for select rules are show below, based on variations in baseline inflation and r*. Increasing the natural rate and the inflation projection contributes to a higher terminal rate for policy over the horizon under consideration.

The content in this piece is partly based on proprietary analysis that Exante Data does for institutional clients as part of its full macro strategy and flow analytics services. The content offered here differs significantly from Exante Data’s full service and is less technical as it aims to provide a more medium-term policy relevant perspective.

Exante Advisors, LLC & Exante Data, Inc. Disclaimer

Exante Data delivers proprietary data and innovative analytics to investors globally. The vision of exante data is to improve markets strategy via new technologies. We provide reasoned answers to the most difficult markets questions, before the consensus.

This communication is provided for your informational purposes only. In making any investment decision, you must rely on your own examination of the securities and the terms of the offering. The contents of this communication does not constitute legal, tax, investment or other advice, or a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. Exante Advisors, LLC, Exante Data, Inc. and their affiliates (together, "Exante") do not warrant that information provided herein is correct, accurate, timely, error-free, or otherwise reliable. EXANTE HEREBY DISCLAIMS ANY WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.

…