Whatever it takes… ten years on

Draghi’s famous speech took place a decade ago this week—but how important was it? A long-term historical perspective.

“Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.”

Mario Draghi, 26 July 2012

THIS WEEK MARKS the 10-year anniversary of Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech, one of the most significant events in the history of the Eurozone—and, indeed, in recent monetary history.

The speech in question was delivered by Mario Draghi—then President of the European Central Bank (ECB), currently caretaker Prime Minister of Italy—and, remarkably, does not have a title. It is recalled on the ECB website simply as “verbatim remarks made by Mario Draghi” at the “Global Investment Conference in London 26 July 2012.”

Draghi had travelled to London to address a conference at Lancaster House “a Georgian mansion that sits between Buckingham and St. James’s palaces,” according to Bloomberg.

Having picked up on the pessimistic mood amongst investors, Draghi rose to deliver his own perspective. After noting that the Eurozone was like a bumblebee—able to fly despite apparently defying the laws of physics—he noted that the ECB would do enough to preserve the euro “and believe me, it will be enough.”

This speech is commonly considered a turning point in the Eurozone Crisis. But how ought this intervention be viewed? And what comes next?

The Great Depression

It’s useful to begin at another time, on another continent.

There was once a large and diverse, but loosely integrated, continent-sized economy—recently united under a single currency and supported by a newly established central bank—that slipped into a deep depression.

That newly established central bank, the Federal Reserve, had been created to adhere to the gold standard while furnishing an “elastic currency” when called upon—overcoming the periodic challenges facing a fractional reserve banking system pyramided upon a finite base of high-powered money.

But the Fed would have to adapt quickly to a changing world soon after she was established in 1913—with the breakdown of global trade and payments due to the Great War and the fiscal pressures that emerged as a result. Even after that war ended, the global economy would not return to the previous constellation of flows that underpinned the classical gold standard.

And so it was, against a backdrop of shifting sands, that the Fed was asked to develop policy tools “on the fly” to deliver on a mandate intended for a simpler time.

As it was, the real work of the Federal Reserve arguably only really began once the post-war boom came to an end at the beginning of the 1920s. And during this first decade the Fed delivered a “roaring” boom that concealed various imbalances.

In this respect, the 1920s resembled what came to pass in the first decade of the 2000s for the Eurozone.

The next decade that followed, the 1930s, involved banking crises and a series of macro-financial shocks that caused the rapid contraction in activity, misery for many, and a Federal Reserve found wanting.

In this respect, the 1930s in the United States had echoes of the 2010s in Europe.

Monetary histories compared

The most celebrated analysis of this catastrophe in the US was due to Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz’s Monetary History of the United States, to whom monetary aggregates spoke most clearly.

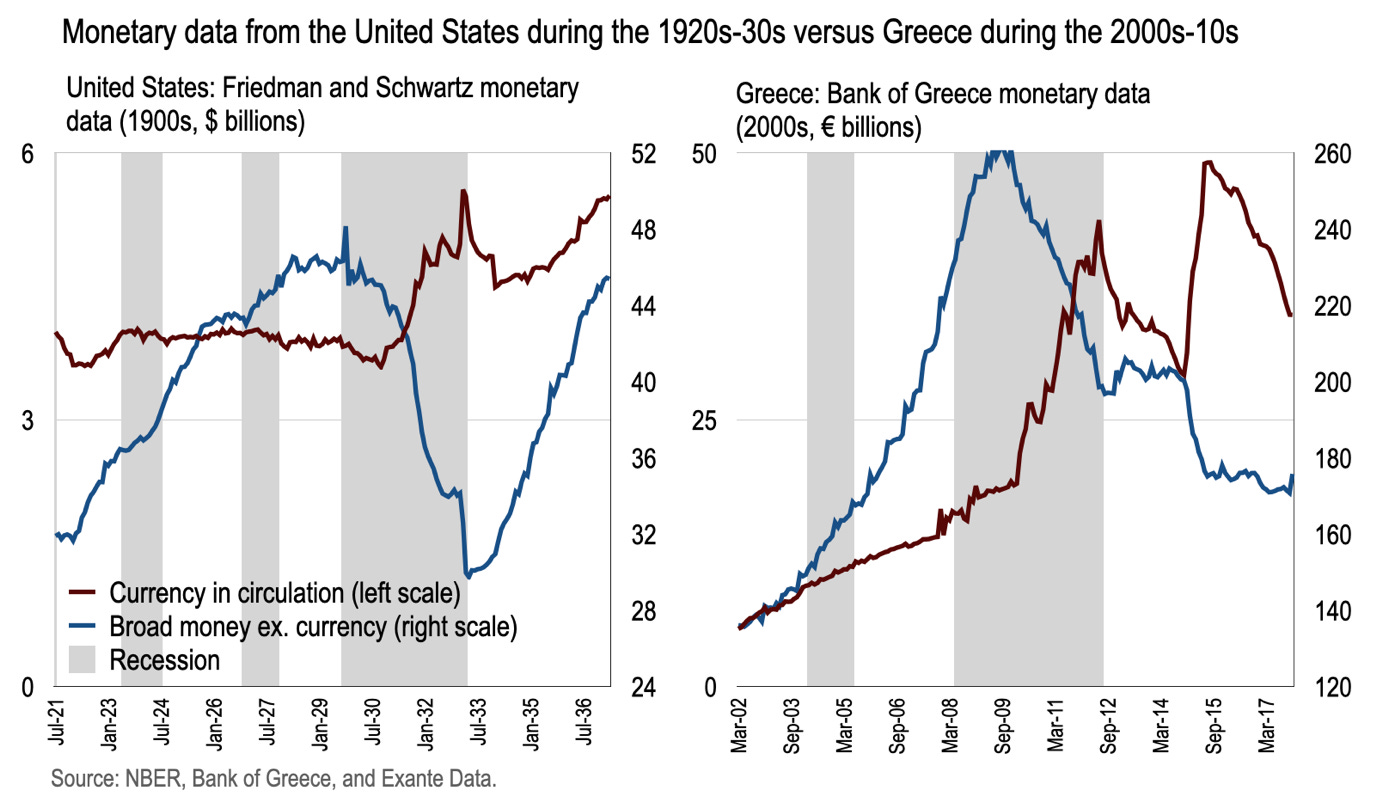

The chart below contrasts their US broad monetary aggregate from July 1921 to April 1937 (on the left) with M3 in Greece from March 2002 to Dec 2017 (on the right.)

Although the definitions of broad money are not identical, the experience for each is similar enough. It is of some interest for later that Draghi’s intervention a decade ago came at the outer edge of the final period of recession in Greece—which is not to imply causation, rather only that it came late into the macro turmoil.

Indeed, from July 1921 until end-1928 broad money in the US (including currency in circulation) grew by 40 percent; this compares with a 97 percent expansion of Greek broad money from March 2002 and August 2009.

Thereafter, in both cases and at various stages, banks deposits were drawn down as depositors preferred the safety of physical cash to an uncertain claim on a local bank backed by assets of dubious quality. Moreover, beyond these immediate portfolio choices by residents, overall broad money in the United States contracted by about 30 percent by mid-1933 before recovering over the next 4 years. For Greece, the percent contraction was about half this over the comparable period between 2009 and 2014, but the contraction continued thereafter in contrast to the steady recovery in the US.

Recall, a large part of the monetary contraction at that time was blamed by Friedman and Schwartz on the failure of the Federal Reserve to use their powers to expand base money. Such base money failure could not be said of the ECB over the past two decades—more on which below.

But the above side-by-side comparison is in any case unfair.

Greece was the extreme case in the Eurozone, whereas Friedman and Schwartz were considering US monetary outcomes in the aggregate. Seen in this light, the average monetary contraction during the 1930s during the Great Depression was worse than the most extreme regional experience during the Eurozone Crisis. However, while the US in the aggregate experienced a monetary recovery after about 4 years, such was not true of the Eurozone periphery.

The Great Depression as balance of payments crisis

Indeed, it was the regional experience in the United States that was alternatively emphasised by Lester Chandler in his book on American Monetary Policy, 1928-41. Chandler noted the contraction in money aggregates was only slight in the financial hubs of New York, Boston and Philadelphia but much more severe in the agricultural regions of the mid-west or even San Francisco.

And for Chandler, the differences in regional monetary experience was an expression of the asymmetric balance of payments shocks faced by different regions, given the lack of automatic stabilizers or integrated banking system:

“A major reason for the high failure rates of country banks... appears to have been large shifts of deposits and reserves away from country areas, these reflecting in large part an ‘unfavourable balance of payments’ of agricultural areas. Such regional shifts might be of little significance in a system composed of a few nationwide branch banking systems...

During the early part of the depression, such areas tended to have ‘unfavourable balances of payments’ with other areas on both income and capital accounts... capital movements from other areas to farmers virtually stopped; in fact, farmers were asked to repay some of their debts to insurance companies and other distant creditors.... their banks were drained of deposits, reserves, and other liquid assets.”

The Eurozone Crisis as balance of payments crisis

While often framed in terms of a public debt crisis, the Eurozone’s Crisis was—and could yet return as—a balance of payments crisis. In this respect, Chandler provides a useful benchmark.

Indeed, it was generally assumed that the “balance of payments” (BOP) would no longer be a constraint following the introduction of the euro—although the US experience during the Great Depression ought to have cautioned against this.

Now, traditionally the BOP is the change in reserve assets (or specie) held by a central bank when clinging to a particular (international) monetary standard—a reflection of the residual claims on the rest of the world once all private or official current and financial transactions are settled.

Such was the belief that the BOP no longer mattered that many Eurozone national central banks (NCBs) stopped publishing their balance sheets after the euro came into existence. As for the IMF, they stopped tracking such balance sheets as part of their surveillance—despite being the fulcrum of IMF conditionality and lending arrangements.

What was re-discovered from about 2008 was the enduring role in NCBs in clearing external claims across the Eurosystem through the TARGET2 clearing system.

Whereas normally a BOP deficit country would experience a loss of reserve assets, in the Eurozone this found expression in debits against the TARGET2 system—and corresponding asset claims elsewhere. In other words, rather than a loss of foreign assets the BOP became an increase in foreign liabilities. And whereas the clearing of specie under the gold standard involves the transfer of outside money, Eurosystem clearing involves inside money—with corresponding claims within the system.

The sum of TARGET2 debits and credit across the Eurosystem, including a few negligible non-Eurozone central banks, is shown in the chart below—these being the month average balances available from 2001.

For the first 7 years, the TARGET2 positions, credit and debit, remained below EUR100 billion and were largely a rounding error in monetary matters. But beginning from around 2008, alongside the GFC, these positions started to increase as banks lost private funding and accessed liquidity instead through repo operations at their NCB.

Recall the Friedman and Schwartz criticism. In contrast to then, base money across the Eurosystem was indeed elastic during the Eurozone Crisis. That is, liquidity was available for the banks, subject to the collateral they could offer and the haircuts applied—and altered as necessary. Alternatively, the NCB was forced onto emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) provision under the careful and continuous oversight of the ECB’s Governing Council.

As such, from mid-2007 and end-2009, TARGET2 debits and credits increased about EUR120 billion while bank deposits with the Eurosystem, or bank reserves, increased by EUR140 billion. From end-2009 to end-2011 these increased a further EUR515 billion and EUR510 billion respectively, supported by the introduction by President Draghi of the Very Long-Term Repo Operations (VLTROs) in late 2011.

In this way, central bank money was used to facilitate capital outflows from peripheral countries, changing the composition of external liabilities in the process.

Indeed, the TARGET2 debits of the Peripheral 4 (Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece) increased from USD20bn in Jan 2007 to reach EUR874bn in July 2012, when Draghi spoke, and peak at EUR890bn in August of that year, before falling about EUR400bn over the next 30 months. Germany’s TARGET2 credit increased from EUR6bn in Jan 2007 to peak at EUR749bn in August 2012.

The interest charged on these TARGET2 liabilities is the marginal repo rate at the ECB, meaning the conversion of external portfolio liabilities and associated coupons to other investment liabilities at around 100bps (at that time, and only 0bps more recently). Such external debt transformation therefore allowed countries to reduce their external interest payments and convert portfolio debt into (perhaps) longer-term deposit liabilities with the Eurosystem.

While it is often emphasised how the debtor countries benefitted from this system, in fact the deal was even better for creditor countries. They were often able to convert a claim on the periphery of dubious quality into a solid claim on the Eurosystem—reducing the riskiness of their portfolio substantially, if lowering the yield in the process.

Moreover, as Lester Chandler observed of the United States, there was a differential monetary response across the Eurosystem. Broad money contracted most in those countries with current account deficits and experiencing financial outflows—such as with Greece above. And so, it was the external accounts that were calling the tune. But this was facilitated by the expansion in base money across the Eurosystem. It is not that the ECB was substantially offsetting pressure on broad money to contract in the periphery and therefore meaningfully offsetting the deflationary impulse. Rather base money became an expression of the clearance of BOP positions between deficit and surplus countries, and the reshuffling of financial claims.

It's the current account, stupid

While much focus at the time was on the adjustment of fiscal positions, perhaps the most important indicator of future funding stress was the external current account balance. And during the first decade of the euro, external deficits emerged across the periphery of a magnitude unimaginable outside the single currency.

The current account deficit in Spain, for example, reached 10 percent of GDP in 2007, Greece nearly 16 percent. Italy’s external deficit was relatively contained below 4 percent—but still substantial.

And though these deficits fell sharply during the initial phase of the GFC, they remained in deficit by 2010 as the Eurozone Crisis took hold. But how could the periphery generate the foreign exchange earnings needed to service their increased external debt due to capital inflows?

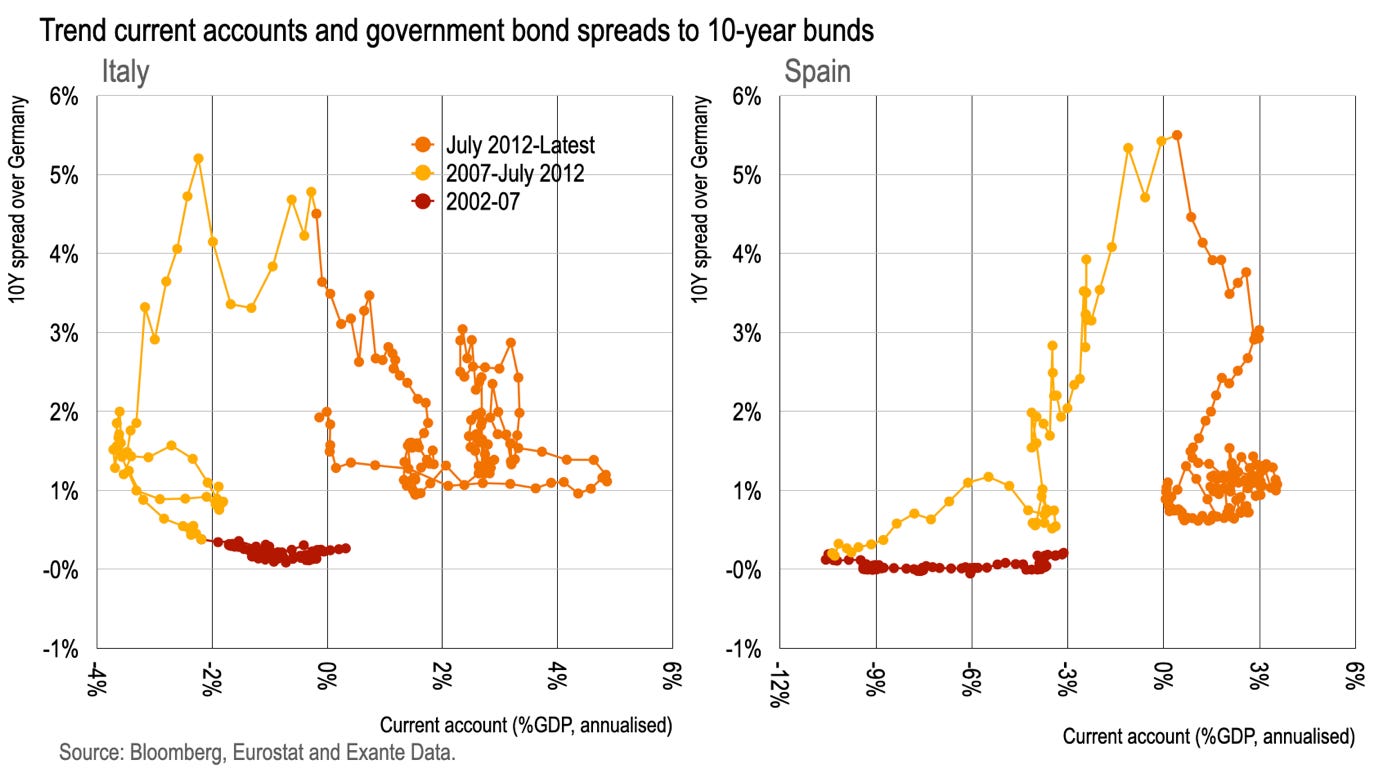

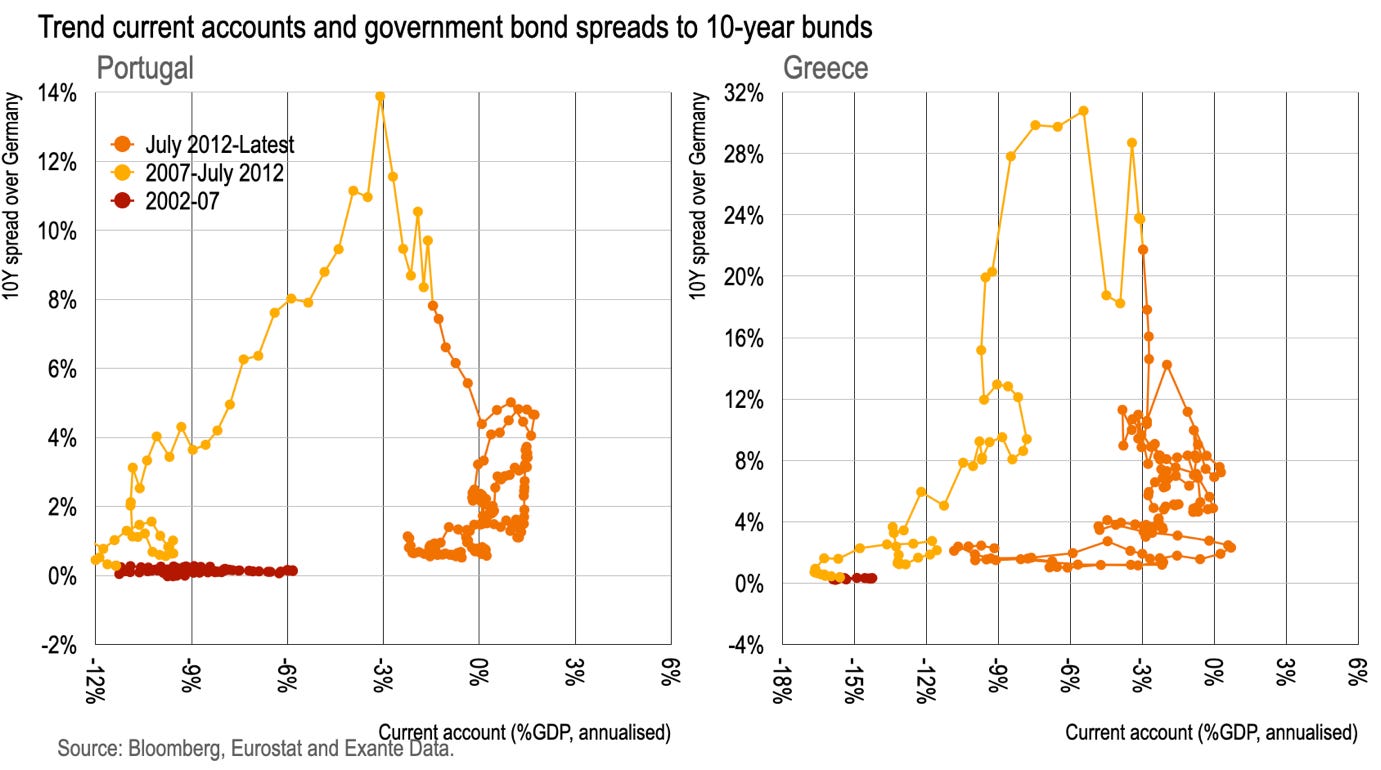

A useful way of illustrating the peripheral dilemma is by constructing a scatter of their trend current account balance (annualized) against the spread of 10-year government bonds against bunds. This involves reshuffling the data in the time series above of peripheral external deficits and spreads.

From 2002-07 such spreads remained near zero despite emerging external risks. Financial markets did not consider such external deficits as suggesting a challenge in the making. Thereafter, from 2007-mid-2012, these spreads increased while current account deficits gradually compressed. The sudden stop of external financial flows, and outflows facilitated by the Eurosystem, drove up financing costs and compressed domestic spending.

These scatter plots trace a clockwise pattern as this process works its way through.

The case of Spain is particularly clear. The spread to Germany remained near zero from 2002-07 despite the current account deficit creeping ever higher to reach 10 percent of GDP. Spreads then increased to about 100bps during GFC while the current account deficit came back to about 4 percent of GDP. But this 4 percent deficit was presented a large external financing need. And the spread to bunds further increased to above 500bps while domestic demand and imports contracted—until at last the current account (underlying trend) was returned to near-balance on the eve of Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech.

For Portugal and Greece the story is similar, through the spread was more extreme and adjustment more chaotic.

Draghi’s speech ten years ago came only after the majority of this external adjustment was complete.

What lessons?

We might suggest four lessons from our trip down memory lane.

First, the situation a decade ago in the Eurozone bears a clear resemblance to the Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s. Only ninety years apart, two new central banks, spanning currency areas across economically crucial continents, were breathed into life with great fanfare—only to oversee the substantial disruption of the economic life of large numbers of residents after about a decade or so.

Second, contrary to the Friedman and Schwartz complaint of the Fed in the 1930s, base money expansion in the Eurozone was hardly constrained. Perhaps it could have taken a different form and done so much sooner—such as through asset purchases from 2010 onwards, rather than only from 2015. But ECB balance sheet expansion was a feature of the experience a decade ago. But this hardly avoided an economic catastrophe as hoped. In fact, such expansion became instead the counterpart to the clearing of BOP flows within the Eurosystem—a necessary part of the external adjustment, but not a solution to offset the forces of depression.

Third, the current account balance was the crucial determinant of macroeconomic performance during the Eurozone Crisis. Deficit countries suffered most, and roughly speaking the larger was the deficit the more painful was the adjustment—and the wider the spread to bunds in the process. Only once current account deficits adjusted to within touching distance of balance did yields and domestic demand stabilise.

Fourth, amongst this cacophany, Draghi’s intervention a decade ago came rather late in the game. Much of the external (current account) adjustment had already happened; the underlying balance in Spain and Italy was already close to balance in July 2012—meaning the goods and service balances had achieved surpluses sufficient to service net external interest payments in full. Perhaps there was a little further to adjust. But only a little. And perhaps this intervention was needed to win round foreign investors once more—and hence unwind the TARGET2 debits that emerged between 2009 and 2012. But the “heavy lifting” of the spending adjustment by the countless, faceless residents of the periphery—the real heroes of the hour—had already by that time nearly run its course.

Conclusions

The Eurozone Crisis provided a second monetary experiment in one hundred years involving the creation of a single currency area followed, after 1-2 decades, by depression-like conditions and privation.

It is a pity these two experiences are not compared more closely by economic historians. It is a pity the lessons from the first were not internalised during the second.

A friend who was close enough to the events surrounding the speech 10 years ago would several months later tell me that Draghi had, before giving his remarks, himself scrawled the words “and believe me, it will be enough” into the margin. If so, this annotated version might be in someone’s possession still, silently waiting to be auctioned into its rightful place in history.

Draghi’s intervention is considered a turning point in the Eurozone Crisis. After all, we all like heroes. And a single hero in a cape (or a blue tie) is easier to worship than the faceless multitude. But Draghi’s intervention was too little and too late. Much of the damage was already done.

Moreover, the design flaws at the creation of the Federal Reserve System nearly one hundred years before were not offset in the creation of the euro. Indeed, they have hardly been internalised since—at a time when the external deficits have begun to widen once more on an energy crisis driven by external actors.

This means the “whatever it takes” speech might not be a full stop in the future history of the Eurozone—but instead a semi-colon.

Regardless, Draghi’s speech retains a mythical status still. Only future economic historians will be able to gain real perspective on our passing events.

The content in this piece is partly based on proprietary analysis that Exante Data does for institutional clients as part of its full macro strategy and flow analytics services. The content offered here differs significantly from Exante Data’s full service and is less technical as it aims to provide a more medium-term policy relevant perspective.

Exante Advisors, LLC & Exante Data, Inc. Disclaimer

Exante Data delivers proprietary data and innovative analytics to investors globally. The vision of exante data is to improve markets strategy via new technologies. We provide reasoned answers to the most difficult markets questions, before the consensus.

This communication is provided for your informational purposes only. In making any investment decision, you must rely on your own examination of the securities and the terms of the offering. The contents of this communication does not constitute legal, tax, investment or other advice, or a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. Exante Advisors, LLC, Exante Data, Inc. and their affiliates (together, "Exante") do not warrant that information provided herein is correct, accurate, timely, error-free, or otherwise reliable. EXANTE HEREBY DISCLAIMS ANY WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.