LAST WEEK delivered another shock election result in Argentina—followed by an 18 percent devaluation, taking the official rate to about 350 Pesos to the dollar. The black-market rate is now above 700 per dollar—the gap that refuses to close.

It has been implied that the step devaluation was due to the election result; more likely this was agreed with the IMF in advance—a decision delayed as a favour to the Finance Minister and Presidential candidate with whom they negotiate.

The IMF Board met yesterday to finalize the combined fifth and sixth reviews under EFF arrangement, releasing about $7.5 billion. This cash will be recycled back into bridge financing and to the Fund; the program is a holding pattern until the new administration is in place. Fixes for underlying imbalances will have to wait.

Milei vanilla?

Macroeconomic instability is hardly a new phenomenon in Argentina. Perhaps most surprising is how long it has taken voters to be offered radical solutions. All parties so far have been slow to consolidate fiscal policy and fill holes on the central bank balance sheet, driving the currency lower and inflation higher. This could now change.

The “surprise” victory for libertarian candidate Javier Milei ought to be unsurprising since he is at last looking for solutions—drastic expenditure cuts and scrapping the central bank.

Given decades of instability and the choice between the “shock therapy” of Milei’s reforms or endless currency disorder and a potential slide into hyperinflation, who would choose the latter?

Still, his proposed solutions are likely to bring much pain. And there may be better ways to proceed. But the parallels from the previous currency reform in 1991 are real and worth noting.

Memories of 1991

The cold war is thawing as the Warsaw Pact was being dissolved, the Dow Jones closes in on 3,000, and Argentina is pushing a new currency experiment. It is April 1991.

This Convertibility Plan was described in glowing terms in the late-1990s thus:

The currency board was a key component of the so-called convertibility plan, an innovative and comprehensive stabilization program to eliminate inflation, and restore macroeconomic balance and long-term growth. The program was based on a strict exchange rate rule, where the parity was fixed by law at one peso per US dollar. In addition, the convertibility law established that the monetary base had to be fully backed by international reserves, while the central bank was restrained from financing budget deficits, thus breaking one of the critical mechanisms that caused inflation in the past. In effect, Argentina established a currency board regime.

To be clear, it was not a currency board proper.

There was never strict 100 percent base money coverage as BCRA, Argentina’s central bank, had some scope to buy domestic assets. Limited “lender of last resort” functions in, “important in exceptional circumstances; such as during the financial crisis that took place after the Mexican devaluation of December 1994.”

Looking back, at least three features of the reform then have clear parallels to today.

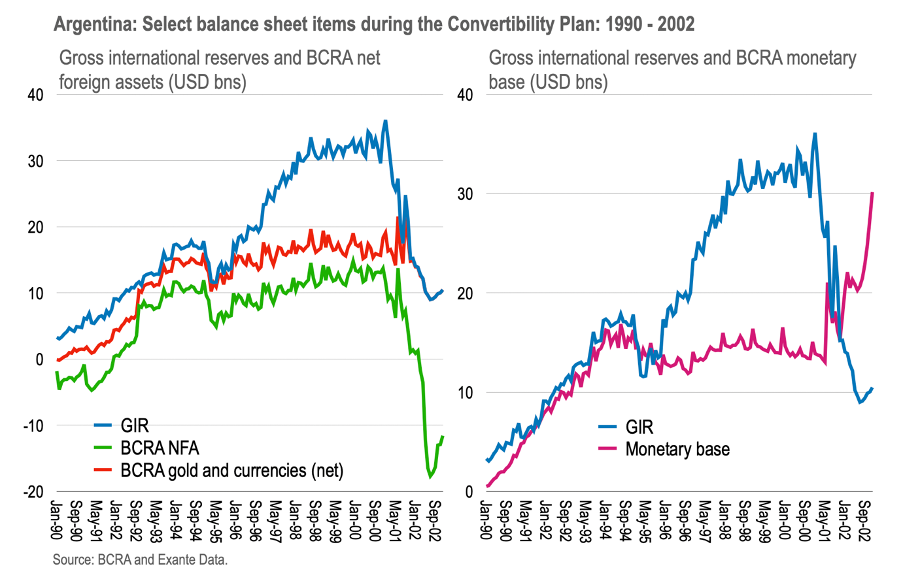

First, the 1991 reform is that it came at a time when BCRA net foreign assets (NFA) were negative, much as they are today. This is shown in the left chart below. BCRA NFA began 1991 at minus USD4.4bn in April 1991 (there was a one-to-one exchange rate at that time). Gross international reserves (GIR) however were firmly positive, at USD5.5bn whereas gold and currencies on BRCA balance sheet were USD0.9bn. It was gross reserves that provided coverage for base money on the basis of which the quasi-currency board was initiated.

Second, the plan ensured the independence of the central bank and “restrained the central bank from financing any fiscal deficit, except through the purchase of government bonds at market prices” with strict limits on the holding of government debt.

Third, the plan also involved eliminating the quasi-fiscal activities of BCRA. It “was crucial to eliminate the quasi-fiscal deficit, whose main origin was the payment of interest on the financial institution’s reserve requirements. While the central bank was remunerating its liabilities it did not earn interest on its assets to generate a compensating revenue stream.” This was “one of the key factors that led to the failure of the stabilization programs in the past.”

Underlining that today’s problems are recurring and nothing new, these three features are repeated almost exactly today.

Why not repeat the Convertibility Plan?

Instead of dollarisation, why not repeat the Convertibility Plan today? Or some variant of it? Well, the most obvious point is that the quasi-currency board ended badly, itself laying the foundations for today’s predicament.

And there were clear reasons that arrangement could not continue.

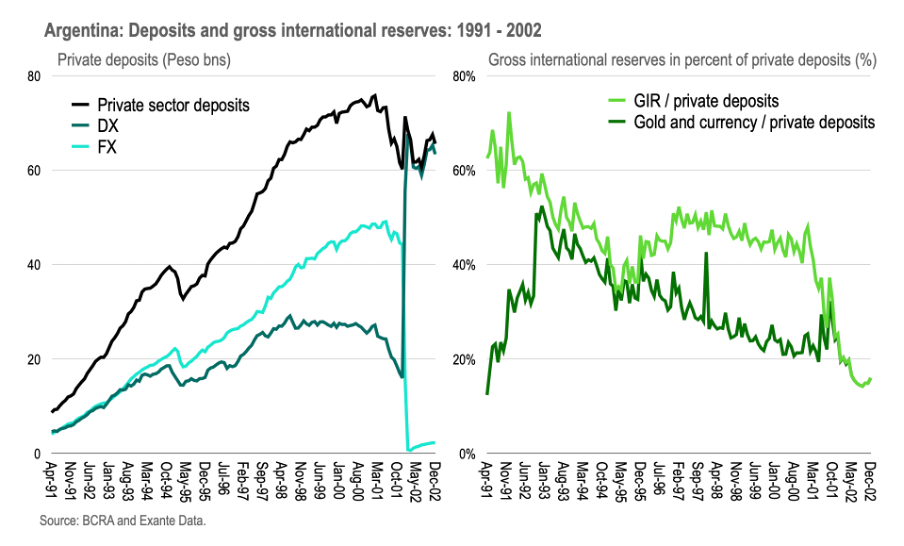

It built a stock of broad money, or private deposits, on an inelastic supply of base money, limited by gross reserves. The reason the quasi-currency board could “get off the ground” to begin with is likely because the hyperinflation of the late-1980s wiped out the value of deposits so that gross international reserves were large to cover about two-thirds of broad money deposits in 1991.

As deposits recovered during the 1990s boom, the scope for a lender-of-last-report response to private deposit flight was gently eroded until, by 2000, private deposits were about 2.5 times base money.

And since gross reserves were largely dedicated to providing cover for base money, there was virtually scope to respond to deposit flight. When deposits began to fall, the quasi-currency board and exchange rate quickly gave way—requiring the conversion of private deposits into DX.

The Federal Reserve in the United States was founded to furnish an elastic currency. In Argentina dangerous inelasticity has been the only solution to fiscal plundering of the central bank.

What happens next?

None of these weaknesses with the 1990s arrangements will be resolved through dollarisation. In fact, broad money and the deposits with the banking system will be left even more exposed under dollarisation.

With the elections not until Oct. and the change of government in Dec., containing the pressure on the banking system from deposit flight will be difficult if not impossible.

Argentina is not liquid and unlikely solvent.

But solving these problems doesn’t need such a rigid solution as dollarisation.

Why not go the route of recapitalising BCRA, confirming the independence of the central bank, while focussing on fiscal and balance of payments sustainability needs given these steps? Then there is at least a chance of avoiding the mistakes from the quasi-currency board and learning from the past. At last.

The content in this piece is partly based on proprietary analysis that Exante Data does for institutional clients as part of its full macro strategy and flow analytics services. The content offered here differs significantly from Exante Data’s full service and is less technical as it aims to provide a more medium-term policy relevant perspective. The opinions and analytics expressed in this piece are those of the author alone and may not be those of Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC. The content of this piece and the opinions expressed herein are independent of any work Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC does and communicates to its clients.

Exante Advisors, LLC & Exante Data, Inc. Disclaimer

Exante Data delivers proprietary data and innovative analytics to investors globally. The vision of exante data is to improve markets strategy via new technologies. We provide reasoned answers to the most difficult markets questions, before the consensus.

This communication is provided for your informational purposes only. In making any investment decision, you must rely on your own examination of the securities and the terms of the offering. The contents of this communication does not constitute legal, tax, investment or other advice, or a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. Exante Advisors, LLC, Exante Data, Inc. and their affiliates (together, "Exante") do not warrant that information provided herein is correct, accurate, timely, error-free, or otherwise reliable. EXANTE HEREBY DISCLAIMS ANY WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.

"Why not go the route of recapitalising BCRA, confirming the independence of the central bank, while focussing on fiscal and balance of payments sustainability needs given these steps? Then there is at least a chance of avoiding the mistakes from the quasi-currency board and learning from the past. At last."

Yes, I agree this would be better approach. But is it a feasible option? Surely, it would have been implemented long before now if it were doable. The fact that it has not happened suggests otherwise. Which brings us back to the radical option of dollarization.

My question, then, is whether the lack of state capacity that has prevented your preferred approach from happening, will also be a constraint to implementing dollarization in Argentina.