The first note in this series revealed the exchange rate assumptions that under-pin the revised IMF program document (February 2024).

We now consider the prospects for central bank sustainability. What’s the plan? And does the IMF document deviate from the authorities’ annoucements?

BCRA balance sheet plans

Argentina’s “program” since 2018 has been undermined as it is defined by a monetary policy Ponzi scheme.

In a nutshell, the BCRA balance sheet (Argentina’s central bank) has few interest-earning assets yet absorbs liquidity by issuing bills at the policy rate. This means “tighter” policy through higher rates brings a faster expansion of liabilities leaving BCRA with no choice but to issue more bills or monetise the cost of conducting monetary policy. This is on top of explicit monetisation of deficits, of course.

Absent growing money demand, such money creation finds expression through exchange rate depreciation and inflation.

Earlier in the program, since BCRA still had positive net foreign assets, exchange rate weakness served to increase assets measured in local currency as a counter-weight to the expansion in liabilities. But as net foreign assets have been eroded over successive periods of attempted external stabilization since, depreciation no longer serves as a valuation offset, making BCRA balance sheet more precarious still.

Balance sheet weakness has been on the radar since the initial program in 2018, but serious solutions were never implemented.

The most recent program had a structural benchmark to at last resolve such challenges by end-Oct 2023. Perhaps predictably, the deadline passed without any progress. And in the latest review, IMF staff have dropped the benchmark. Why? We are told (¶48, p.25)

Since the authorities are already implementing an ambitious plan to gradually improve the BCRA balance sheet, the resetting of the related missed end-October 2023, SB [structural benchmark] is not proposed.

What exactly is the new plan? In general, the stabilisation plan is said to include “a strengthening of the monetary policy framework and the central bank’s balance sheet” (¶16, p.12.) The improved monetary policy framework (described in ¶48) is being combined with the following (¶39, p.22):

The authorities have developed and are implementing an ambitious plan to gradually strengthen the central bank balance sheet. The plan is centered on eliminating all direct and indirect monetary financing of the fiscal deficit, as well as prohibiting all profit distributions. This is being complemented by ongoing efforts to boost reserves (including through the FX correction), and real money demand as the stabilization plan takes hold (through an organic reduction of central bank liabilities). The authorities would aim to (i) encourage a very gradual shift from BCRA securities to government securities, as conditions allow; (ii) enhance the quality of central bank assets; and (iii) further adopt international accounting standards to transparently lay out the BCRA’s vulnerabilities and establish a target equity range.

Still, the section on program safeguards warns (¶52, p.27):

while important efforts are underway to strengthen the BCRA’s balance sheet, more work is necessary to improve its financial and institutional autonomy. This includes reform of the BCRA’s legal framework and full adoption of international financial reporting standards (IFRS)

What’s projected?

Such is the plan. But it’s disconcertingly vague. For example, the elimination of monetary financing was a feature of the original Massa program in 2018, but BCRA built up flow vulnerabilities due to negative net interest income as interest rates were increased. In the end, the exchange rate gave way and inflation followed.

As a historical aside, the introduction of the currency board arrangement during the Convertibility Plan (and short-lived stabilization) in the 1990s was accompanied by the following reflection on prior experience:*

it was crucial to eliminate the quasi-fiscal deficit, whose main origin was the payment of interest on the financial institution’s reserve requirements. While the central bank was remunerating its liabilities it did not earn interest on its assets to generate a compensating revenue stream.

As was the case before the 1990s stabilization, the central bank has since the 2010s been a constant source of monetary expansion due to her balance sheet weakness.

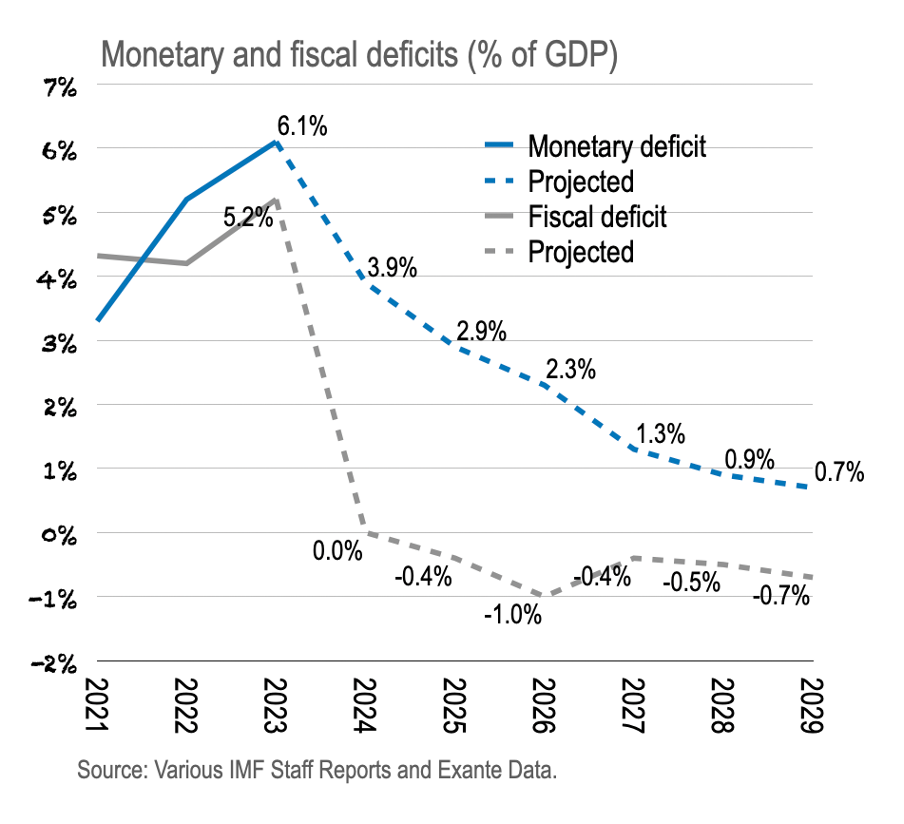

The chart below shows the IMF’s measure of the monetary deficit (Table 6a, p.61). The monetary deficit was larger in 2023 than the fiscal equivalent.

The program assumes the large, upfront fiscal adjustment is accompanied by, or provokes, a steady improvement of the monetary deficit from about 6% of GDP in 2023 to only 4% in 2024, 3% in 2025 and down to only 1% of GDP in 2028.

Why should the fiscal adjustment take precedence? Or, more precisely, why is it not accompanied by actions to eliminate the monetary deficit?

We might also ask, where does the gradual improvement in the monetary deficit come from?

If we express this deficit relative to the previous period stock of central bank securities—an implied interest—the net interest deficit declines in line with the projected disinflation from 2025 onwards. After CPI spikes in 2024 due to the exchange rte adjustment in late-2023, gentle disinflation allows the policy rate to decline and, in turn, the monetary deficit to moderate.

This makes sense if the inflation rate is exogenous to balance sheet expansion. But a reasonable interpretation of recent developments would emphasise that tight money causes monetary deficits, exchange rate weakness, and then inflation.

In any case, the monetary accounts (Table 6a, p.61) give some further hints at the plan.

Converting key balance sheet items into USD uncovers some interesting, if strange, balance sheet activity. Net credit to the public sector is projected to increase by USD37bn in 2024 on end-2023. In part, this is offset by a USD23bn increase in (the negative of) other items (net.) “Other items (net)” (OIN) is a catch-all of other balance sheet items, including central bank capital.

We might puzzle about the increase in net credit to the public sector.

Indeed, as the Staff Report explains on several occasions (such as ¶32, p.19):

The authorities also committed to stop all BCRA financing of the public sector, including through profit distributions and purchases of government debt in the secondary market. Furthermore, purchases of government securities related to the exercise of put options by the BCRA are expected to be fully compensated by government redemption of securities held by the BCRA, consistent with the strengthened zero ceiling on monetary financing under the program.

The projected increase in net credit to the public sector, at first blush, contradicts this plan.

But the more negative OIN provides a (partial) explanation. If the increase in net claims reflects a recapitalisation of the central bank, this would have a counterpart move in BCRA equity, reflected in OIN. The complication being that the increase in net assets is substantially larger than the increase in OIN!

We can get to the same matter in a different way.

There are two sources of central bank liquidity over the projection period. First, the increase in reserve assets (measured at period average exchange rate), second, the monetary deficit. (Note, net credit to the government is ruled out.) Against this, such money creation can be absorbed through an increase in base money or BCRA securities. The sources of liquidity and their absorption are summed and compared in the chart below (left) along with their difference plotted (in percent of GDP, right chart).

We see the initial projected expansion in BCRA liabilities (base money plus securities) is far larger than the projected sources of liquidity. The gap in the 2023 data (historical) can be explained by monetary transfers to the government being not captured here and timing issues (year average exchange rate will not capture the true flow.)

The projections, however, should not contain such a discrepancy.

One possible explanation can be ruled out immediately. Government deposits at end-2023 were about ARS1 trillion; even if they were run down to zero we are a long way from filling the ARS23 trillion gap.

More likely this discrepancy is simply the counterpart to the difference between the increase in net credit to the public sector and the change in OIN noted above which is difficult to explain.

The “good news” here is that, if other aspects of future balance sheet flows are correct (due to reserve accumulation and the monetary deficit) then the true expansion in central bank liabilities may be lower than projected over the period 2024-26. Against this, it is difficult to have much confidence in the monetary program as constructed.

Conclusions

Milei’s stabilization program, as expressed in the IMF’s latest staff report, largely focuses on fiscal adjustment with the promise of actions to support BCRA balance sheet at some point. This is a repeat of previous plans which eventually failed, a strange risk to take by a supposed hard money man.

Meanwhile, the program document elaborates on one version of what this balance sheet support might involve. Indeed, there appears to be an effort to model a recapitalisation of BCRA through a nearby USD40bn increase in net claims on the government despite the prohibition on credit creation.

This recap is not described in the text meaning it is hard to gain any confidence that this is the intended outcome of the Argentine authorities.

In any case, as with the exchange rate, there is a gap between the rhetoric of the staff report and the logic of the tables that support the program.

Still, any recap brings implications for fiscal sustainability. Can we trust the debt sustainability framework? This will be the subject of the third post in this series.

* Miguel Alberto Kiguel, 1999, The Argentine Currency Board. Note, this piece is a celebration of the success of the 1990s and was written before the collapse in 2000-01.

The content in this piece is partly based on proprietary analysis that Exante Data does for institutional clients as part of its full macro strategy and flow analytics services. The content offered here differs significantly from Exante Data’s full service and is less technical as it aims to provide a more medium-term policy relevant perspective. The opinions and analytics expressed in this piece are those of the author alone and may not be those of Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC. The content of this piece and the opinions expressed herein are independent of any work Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC does and communicates to its clients.

Exante Advisors, LLC & Exante Data, Inc. Disclaimer

Exante Data delivers proprietary data and innovative analytics to investors globally. The vision of exante data is to improve markets strategy via new technologies. We provide reasoned answers to the most difficult markets questions, before the consensus.

This communication is provided for your informational purposes only. In making any investment decision, you must rely on your own examination of the securities and the terms of the offering. The contents of this communication does not constitute legal, tax, investment or other advice, or a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. Exante Advisors, LLC, Exante Data, Inc. and their affiliates (together, "Exante") do not warrant that information provided herein is correct, accurate, timely, error-free, or otherwise reliable. EXANTE HEREBY DISCLAIMS ANY WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.