Reviving the SDR for the next century

Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) failed to deliver global liquidity post-Bretton Woods; a crypto-revamp could revive the SDR and help support climate goals.

USD650bn of the International Monetary Fund’s synthetic currency, the Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), today hits the balance sheets of IMF members as a response to the pandemic. The scramble to leverage this allocation for development and climate change underlines how far from the SDR’s original purpose—as the elastic provision of global liquidity—we have traveled. Yet the emergence of cryptocurrency technology suggests ways the SDR could be revamped for the global challenges ahead. With imagination and ambition, such a revamp would allow developing economy savings to be channeled into productive investments rather than financing the US current account. This would be a genuine watershed in the fight against climate change.

Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) are a synthetic currency created in 1969 which—following the collapse of the Bretton Woods System in 1971—were agreed should serve as the principal reserve asset of the international monetary system. (See Article VIII of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement.)

Today a USD650bn (SDR456bn) general SDR allocation in response to the pandemic will reach the balance sheets of most IMF members. This will take total SDRs outstanding to about USD940bn (SDR660bn.)

While welcome, this allocation—in response to the first global pandemic in a century—underlines how, instead of providing a steady supply of liquidity to underpin a growing world economy, we now rely on sporadic allocations of our global reserve asset only in times of crisis. The SDR has become a tool of development rather than serving to stabilise the international monetary system.

In other words, as originally intended, the SDR has failed.

Meanwhile, recent innovations in private digital—or crypto—currencies help place the failure of the SDR in sharp relief. Consider this: the market capitalisation of Bitcoin—a digital currency barely a dozen years in existence—is today about USD900bn. That is, Bitcoin alone is comparable in value to the entire stock of SDRs allocated since 1969 as of today.

With respect to currencies, as with much besides, the private sector innovates while the official sector procrastinates.

But couldn't recent crypto innovations breathe new life into the SDR?

What are SDRs?

It’s useful to begin recalling what the SDR is and how it works. A useful Q&A is available here.

The SDR is a synthetic currency invented in the 1960s to provide global liquidity at a time when the Bretton Woods system was acknowledged to be internally incoherent.

The SDR derives its value from the weighted average dollar price of major reserve currencies (USD, EUR, JPY, GBP, and RMB) and is therefore a derivative of sorts. The largest weight in this calculation is on the dollar, of course. The SDR carries an interest rate given by the weighted average 3 month money market rates of the five underlying currencies.

When SDRs are allocated, as today, they are shared amongst IMF members according to quota share. Each member will record a credit to gross reserve assets of this amount—offset by a long-term other investment liability in the balance of payments. There is no change in net external claims initially. Nor is there an increase in inside claims between IMF members as all initial net claims are zero. In a sense, an SDR allocation creates an outside asset for the international community—similar to gold, but without the need for extraction.

Though net external claims are not impacted initially, the allocation increases the liquidity of the international monetary system since they register as gross reserves. For example, by Monday afternoon Brazil will have roughly USD15bn in additional gross reserve assets, useful for balance of payments purposes, compared to the previous Friday—that’s about a 4 percent addition to her prior stock of non-gold reserves.

Since SDRs cannot themselves be spent, in what sense are they liquid? This is where the Fund’s “SDR Department” comes into play. The SDR Department is a separate part of the IMF where all holdings and transactions in SDRs are facilitated.

If Brazil wished to draw her new SDR allocation this afternoon they would put in a request to the SDR Department convert these into, say, US dollars. In the first instance, the SDR Department would arrange to exchange these SDRs into dollars with other members within the department on a voluntary basis. For example, China might convert USD15bn in claims on US Treasuries for SDRs at the SDR Department, transferring these dollar claims to Brazil. What if there are no volunteers to supply dollars? Absent voluntary transactors, “a mandatory designation plan on members with sufficiently strong external positions” would be triggered. To date, voluntary transactions have always been enough to meet SDRs sales.

Unlike IMF programs, SDR liquidity is unconditional. It can be drawn upon without any policy commitments and without the rigmarole of a negotiation or imposing Memorandum of Understanding. Moreover, there is no obligation to repurchase the SDRs over any particular horizon.

Building BRICS

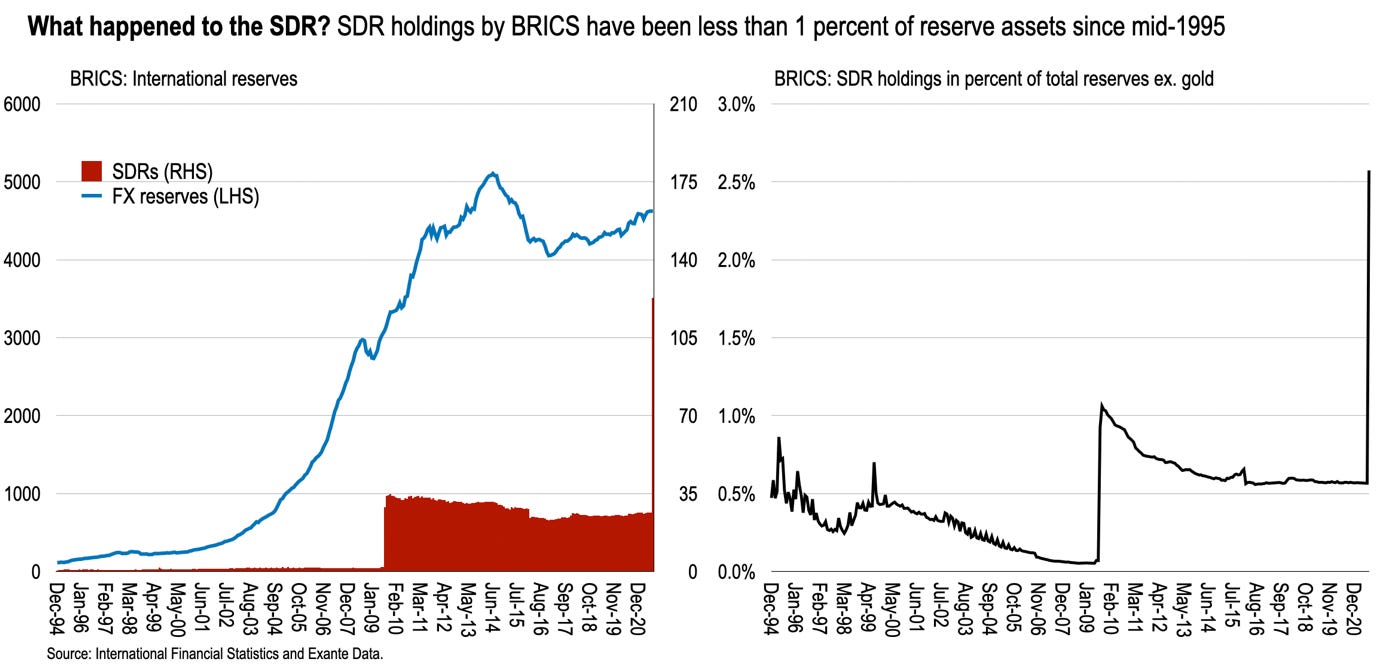

To frame the role of the SDR over the past three decades, it is instructive to witness the rise of the BRICS (of course, Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and the contribution of SDR holdings to their growing demand for liquidity.

In 1994, the combined foreign exchange reserves of the BRICS was about USD110bn with SDR holdings USD0.5bn; by 2008 these reached USD2,800bn and USD1.5bn respectively. SDR holdings were boosted to USD29bn in August 2009 when the post-GFC general allocation was received. Yet, following this allocation, BRIC reserve asset accumulation continued at a considerable pace, with USD1.3 trillion added over the next 2 years—several orders of magnitude the SDR allocation.

Put another way, what SDR allocation over 2009-11 would have been sufficient to allow the BRICS to accumulate the equivalent gross reserves? Their combined quota is about 15 percent. So, USD8.8 trillion!

On average, SDR holdings have been less than 1 percent of BRIC reserve holdings throughout. The latest allocation takes SDR holdings to about 2.5 percent of these reserve assets—a record high, but still slender compared with their overall demand for reserves.

In other words, the SDR has played a minimal role in fulfilling the overall demand for liquidity amongst emerging market economies over the past 3 decades. Allocations are irregular, immaterial, and only follow global crises.

For example, with Monday’s allocation, of the total SDRs allocated, 94 percent will have been provided in response to global crises (GFC and today) and only 6 percent from multi-year allocations aimed at liquidity needs (mainly as agreed in the 1970s, topped up for new members in 2008).

The SDR as crypto pioneer

The failure of SDR to take off is a crucial failing during the post-Bretton Woods era. It has distorted international capital flows and real resource allocations—with consequences for the reserve currency as well as peripheral countries.

This failure is brought into even greater relief when compared with the rise of crypto currencies over the past decade—themselves synthetic currencies, but on the basis of private initiative and guile.

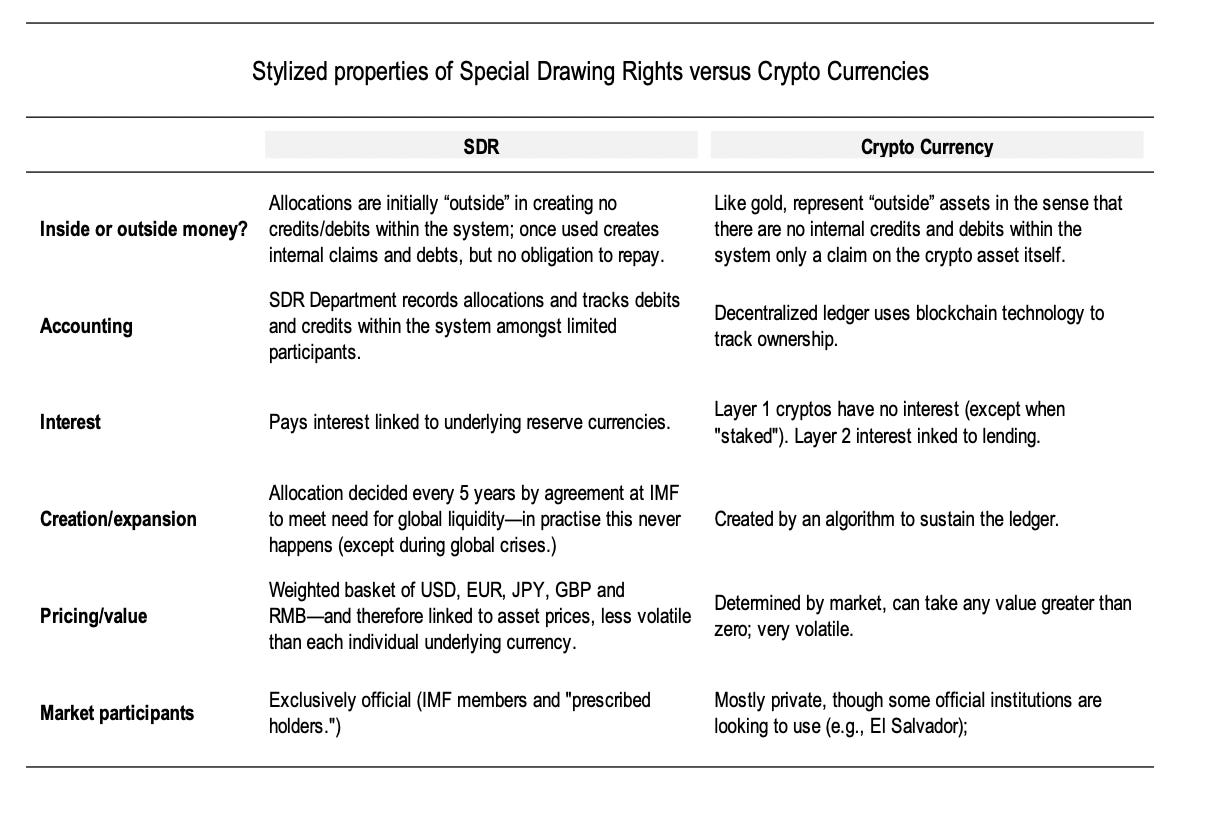

The table below summarises in broad-brush terms the key differences between the SDR and major crypto currencies.

Broadly speaking, the key differences are five.

While the SDR relies on the SDR Department to track holdings, crypto relies on distributed blockchain technologies to keep a ledger of holders;

The SDR price, linked to underlying reserve currencies, is more stable than most non-“stablecoin” crypto currencies;

SDR pays interest—not all crypto currencies do;

Participants in crypto are largely private, whereas the SDR Department can only be accessed by IMF members and other “prescribed holders” (development banks and the like.)

Crypto currency units are created by an algorithm according to some set protocol whereas SDRs are highly inelastic and only allocated sporadically.

Yet now this crypto technology has been tried and tested, it sets up new possibilities for the SDR. In particular, instead of being available for exchange amongst official sector participants of the SDR Department, the SDR could be provided to private actors using blockchain technologies, creating a more stable asset value for crypto enthusiasts while de-linking SDRs from overall reserve assets.

Revamping the SDR

There has been a particular need within the crypto space to have reliable stablecoins in order to manage exposures. This has been met with a number of stablecoins already in circulation acting as proxies to specific fiat currencies, backed by reserves generally controlled by private groups. Additionally, the promise of central bank digital currencies may provide more trust in the stablecoin realm.

What would make an SDR-based crypto stand out from current stablecoins is both the IMF’s backing and the basket of fiat currencies that make it up.

On the technological side, there are ostensibly two ways for the SDR Department to think about implementing an “SDR coin.” Either create their own in-house blockchain (considered Layer-1) or build it atop existing blockchains (creating a Layer-2 protocol). Both come with major trade-offs that likely mimic some considerations slowing the establishment of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs).

Should they choose, like Tether, to piggy-back on existing blockchain technologies (via smart contracts and the like) the SDR Department could avoid the need to implement and maintain technological infrastructure and associated costs. Existing chains already have the ledger and maintenance handled in a distributed way, generally engendering trust among enthusiasts. However, it would be subject to variable fees and traffic congestion that may be happening on the chosen underlying chain(s) making it harder for participants to transact. And it is a major risk to rely on a blockchain that may not be favored by miners/validators/wallets in the future.

Implementing their own blockchain, like China’s digital renminbi or the upcoming Diem, has the unique advantages of being extremely fast and not needing to require fees from participants. However it generally requires the distribution of bespoke wallet technology in addition to blockchain processing infrastructure overhead.

Regardless of what technology is chosen, a digital form would allow them to either mimic the current form (official participants only, deliberate allocation of new issuance, maintenance of inside claims, etc.) or to open the use function of the SDR to private markets.

The advantage of allowing private sector holders of SDRs is that it increases the scope of future SDR issuance. At the moment, the maximum SDR allocation is linked to the outstanding reserve currency holdings that can be exchanged by members of the SDR Department. There might be a limit on how much official participants are prepared to exchange into SDRs—in the limit, for example, this would be like the TARGET2 system of the Eurozone, with concern about the value of claims on the system in the event of a change in monetary arrangements.

With private sector access to SDRs using blockchain technology, the scope for issuance is greatly expanded and limited only by private demand.

Linking SDR allocations to climate-related investments

This brings us to the main problem with SDRs over the past half century—they have not been supplied regularly and therefore have been delinked from with the growing world economy. Perhaps this is because, although no-one will say it, there is limited enthusiasm for clearing balance of payments through the SDR Department.

If instead SDR allocations could be automatically linked to some macro-variables—growth of trade or global nominal GDP—this would help provide assurances that liquidity will grow in the future, helping countries build macro-programs with such supply in mind.

More radically, given the challenge of climate change, linking future SDR allocations to climate-related investments would support economies adjust to the environmental challenge of the next century.

For example, in 2019 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that USD2.4 trillion in annual investment would be needed to meet the challenge of climate change—which is roughly 2 percent of global GDP.

For emerging and developing countries, this investment implies pressure on their balance of payments other things equal. If they attempt to further augment international reserves as their economies grow, then domestic saving will have to increase further to provide space for both climate investment and reserve asset accumulation.

However, if SDR allocations were linked to climate-related investments then there would be less pressure to be concerned about accumulating liquidity—essentially allowing global seigniorage to be put to use to help meet the challenge of the climate emergency.

Conclusions

Today’s allocation provides an opportunity to rethink the role of the SDR in the global economy. At a time when digital currencies are growing in popularity, the global community should be rethinking how the SDR is accessed and the future provision of global liquidity.

By opening up the SDR Department to private sector participants through the use of blockchain technology, the potential for SDR allocations in the future is much greater. And linking these allocations to climate-related investments would allow emerging and developing economies to meet the climate emergency head-on with less concern for accumulating US dollar liquidity—and the distortions this brings.

After the 2009 Global Financial Crisis the Governor of the Peoples Bank of China, Zhou Xiaochuan, announced, “The world needs an international reserve currency that is disconnected from individual nations and able to remain stable in the long run, removing the inherent deficiencies caused by using credit-based national currencies”.

He proposed SDRs, and Nobelists C. Fred Bergsten, Robert Mundell, and Joseph Stieglitz agreed, “The creation of a global currency would restore a needed coherence to the international monetary system, give the IMF a function that would help it to promote stability and be a catalyst for international harmony”.

Beijing began valuing its yuan against a currency basket in 2012 and the IMF made its first SDR loan in 2014. The World Bank issued the first SDR bonds in 2016, Standard Chartered Bank issued the first commercial SDR notes in 2017, and the world’s central banks began stating their currency reserves in SDRs in 2019.