The End of US Exceptionalism

As a narrative and in the hard money flow things are evolving fast

For some months, the US looked exceptional. Better vaccine roll-out. Bigger fiscal policy push. Bolder reopening. And economic and market indicators showed it, too. Consumption spiked well above pre-pandemic levels and US yields started to move higher in anticipation of ‘normalization’. Finally, equity investors put a huge bet on US equities, with foreign investors accumulating US stocks at unprecedented speed in 2020 and into 2021. But there are cracks in the exceptionalism narrative, and the money flow are at risk of a dramatic reversal.

We do not have to show the macroeconomic numbers in this post. It is well-known that the economic recovery in the US has been very swift, and the debate has even shifted from ‘strong growth’ towards ‘overheating risk’.

But what is perhaps less known is how incredibly large the amount of money betting on a strong US economic recovery have been. Hence, we will show this data in some detail…

Exceptionalism in Money Flow

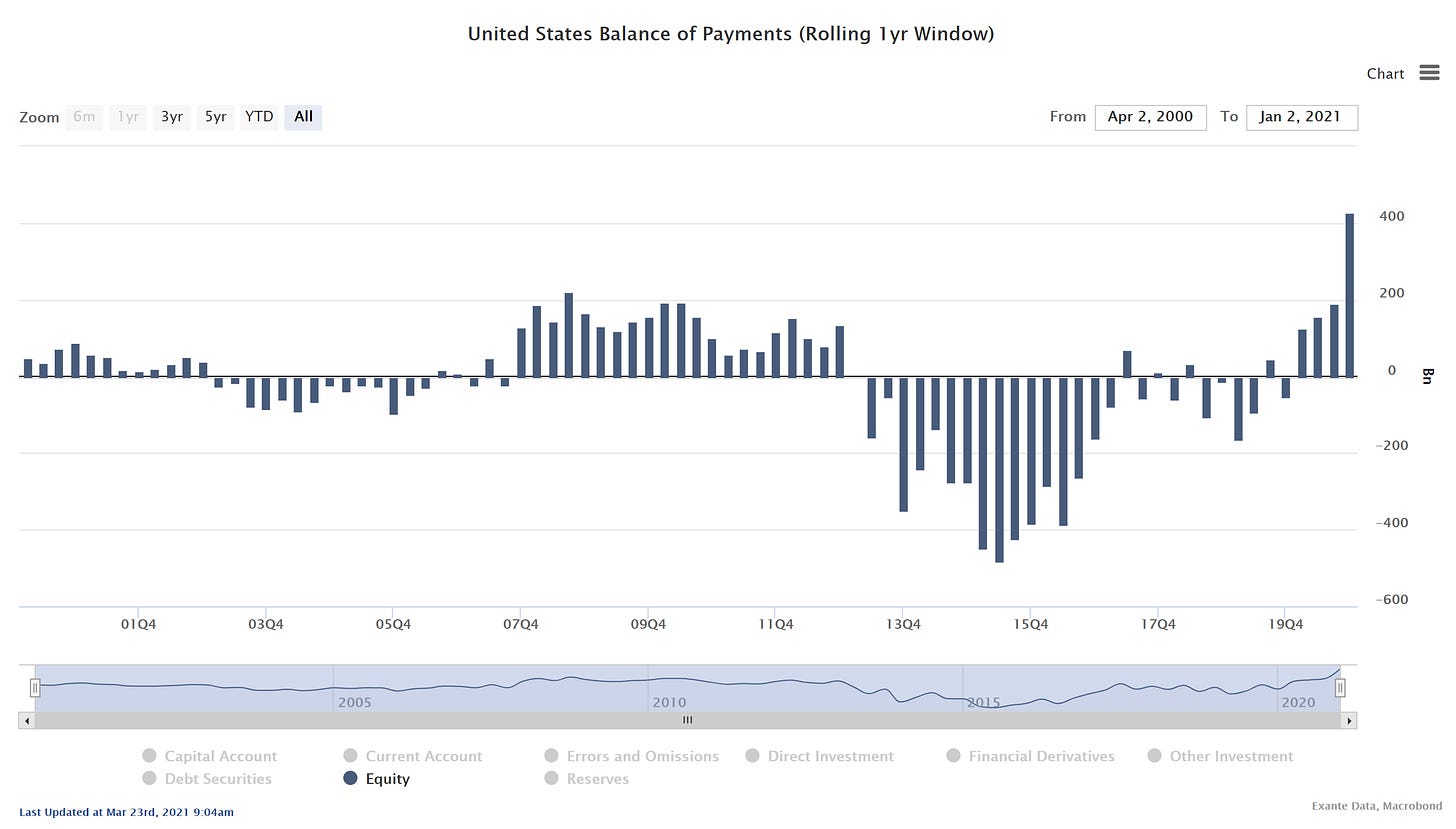

The chart below shows foreign net equity inflow into the US since 2000 based on balance of payment data. For several quarters, the US attracted historically large equity inflows, with net foreign inflows of more than $400bn in 2020.

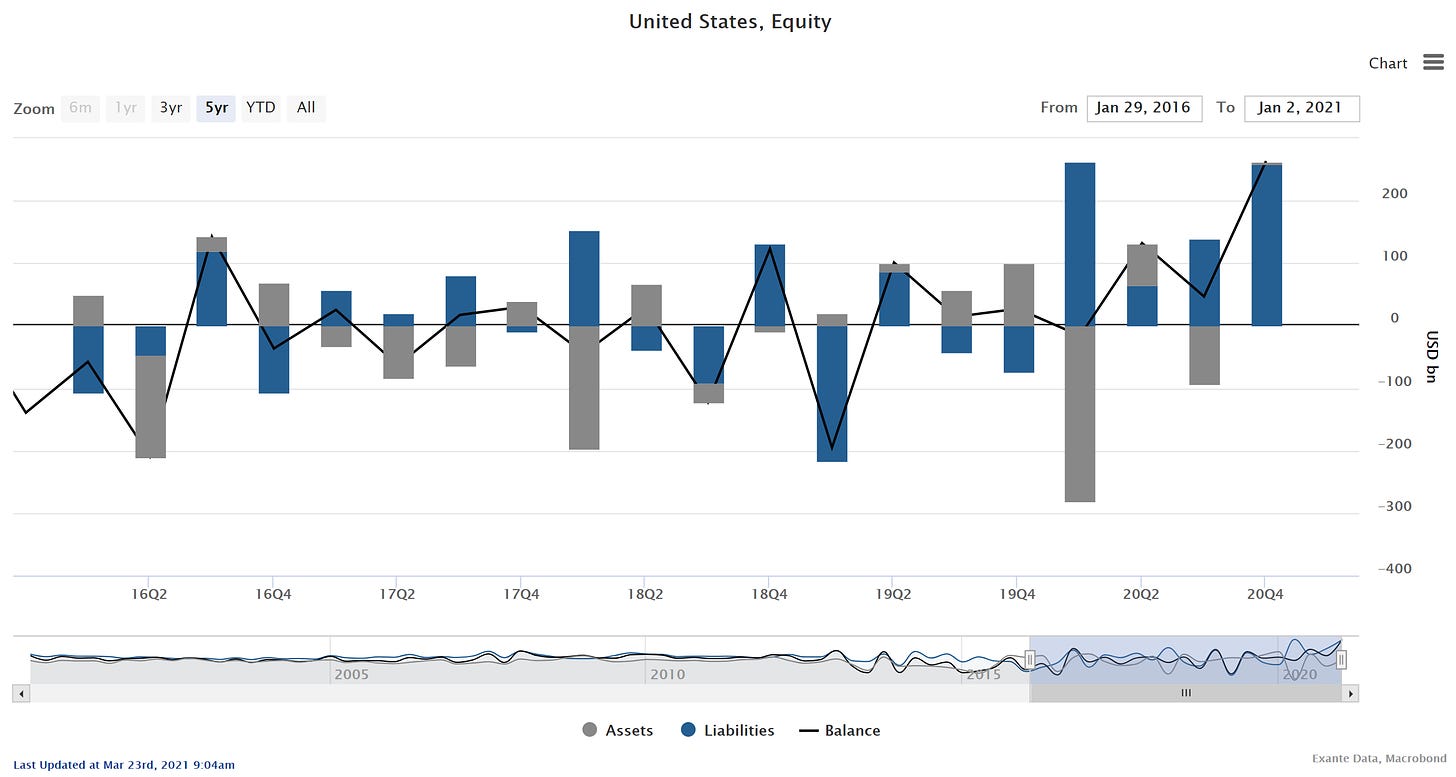

The next chart shows the balance of payments data broken down into inflows (liabilities) and outflows (assets). It highlights that the inflows were the driving force of the large net numbers and that they accelerated during 2020.

The foreign inflows in Q4 2020 alone were >$250bn (>$1 trillion annualized) and therefore in the region 5% of GDP. Even during the 1999-2001 dotcom bubble, we did not see many quarters above 2% of GDP.

We can illustrate the US exceptionalism in this funky chart, too, which shows the US ‘market share’ in total global cross-border equity flows. The US has indeed been ‘exceptional’, grapping nearly 100% of recent gross flow in the world (caveat: some flows to specific countries can be negative).

But exceptionalism is now in question

Enough about the past. Where are we now, and where are we heading? There are many pieces of evidence that investors are questioning the ‘exceptionalism narrative’ and changing the direction of money flow:

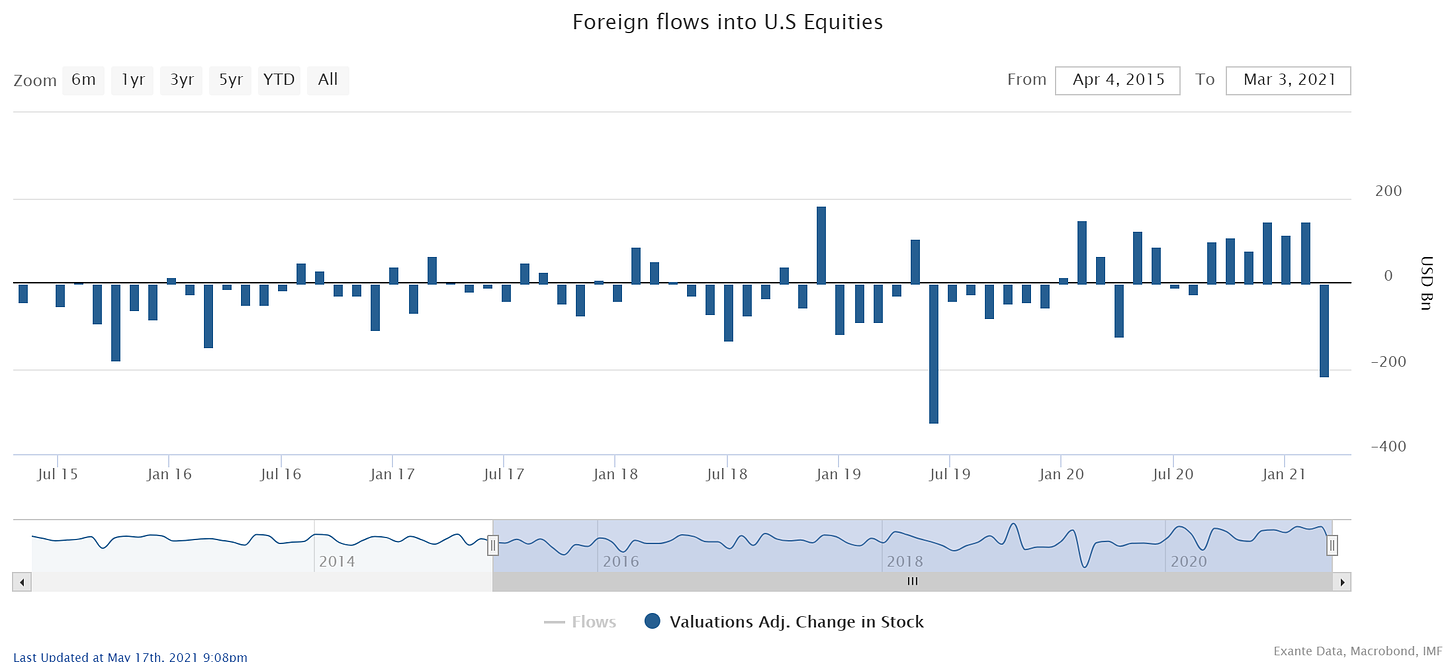

First, the latest official monthly data (the March TIC data published earlier this week) shows that foreign appetite for US equity is potentially waning in an important way. The very strong momentum from 2020 continued into January and February 2021. But there was a big reversal in March.

Second, in a way this is all logical, since the rest of the world is catching up with the US on the vaccine front. The chart below shows that the EU began to vaccinate more people (per capita) than the US in May. And in the past week, China has also surpassed the US (and the EU). This means that other countries are quickly catching up in terms of ‘immunity’, and economic reopening will follow shortly thereafter.

Third, US yields, which spiked in Q1, are no longer leading the global move higher in interest rates. The chart below shows how US 10Y yields rose by 0.8 percentage points in Q1 (blue bars), much more than European yields. But in Q2 (orange bars) the ranking is totally different. European yields are rising the most, while US yields are actually dropping!

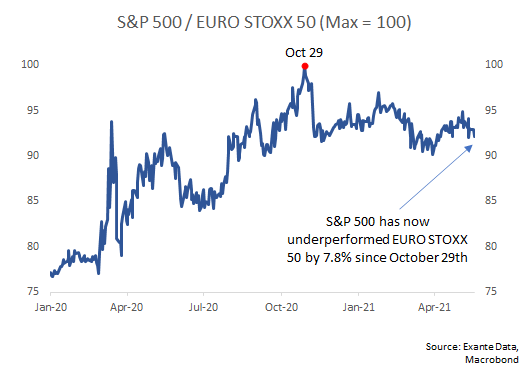

Fourth, relative equity market performance is starting to flip. After a long period of structural US equity market outperformance, we are seeing US leadership in question. Relative to Eurostoxx (the index of the most liquid European stocks), the S&P500 began to underperform since October. This could well have further to run, given valuation differences - and especially if tech exposure turns into a drag in the US, as recent price action suggest.

Conclusion

We can already observe a form of divergence between US equity performance (erratic) and the underlying economic performance (still strong). And the money flows make that picture more understandable: money flows into the US equity market got so extended that some mean-reversion was inevitable.

Less demand for US equity products has implications for relative US equity performance, and may also impact the dollar via the overall structure of balance of payment financing. The last bit is a complex matter, and something we will discuss in a separate substack. But it is a problem in the context of a widening current account deficit, as we have discussed before (link).

The US has an exceptional fiscal stance and an exceptional current account position. If financing via equities is getting less exceptional, something else will have to give.