Three Proximate Macro Factors

Liquidity, the manufacturing cycle, and geopolitics are key drivers of equity performance

While there is a long list of possible drivers of equity performance from the macro perspective, three are particularly useful;

Liquidity meaning domestic money creation in particular, but also cross border flows;

The manufacturing cycle, reflected in the PMIs, offers a useful read on turning points for equities;

While politics and geopolitics, especially abroad, can be a useful lead on equity performance—and can also impact different sectors in different ways.

Two recent posts have discussed the macro factors in equity investing.

In the first, we argued that recent events have revived macro analysis as an integral part of the investment process. Before then, and for several decades, fund managers preferred a bottom-up approach and spent little time analyzing a generally favorable macro context.

In the second, we explored the big picture ultimate macro factors that make a country prosperous and investable in the long run. We proposed that these factors fall into three large categories—innovation & productivity; demographics & health; and society & governance—and that prosperous countries ranked highly on these measures.

We now consider the more proximate macro factors that impact the equity market.

Proximate factors

Proximate factors include macroeconomic measures as well as non-economic.

Some lead the equity market in the sense that their most recent data point is not yet priced in by the market. Others are synchronous with the market, meaning that they are priced in real time. And others lag the market and were already priced by the market yesterday or last week or last month. For obvious reasons, only indicators that lead the market (not yet priced in) are useful to investors looking to adjust their positions.

The list of indicators that lead the market is long and varied. But in this post, we will focus on the three that we regard as most impactful: liquidity, manufacturing, and politics/geopolitics.

Liquidity

One of the main drivers of the equity market is liquidity. Liquidity is the sum of several variables that directly and indirectly increases or decreases the amount of money that is going into or out of the stock market. When liquidity is high, the funds available for investing or trading will be plentiful and equities will experience inflows, pushing indices higher. And when liquidity is low, the funds available will be scarce and equities will experience outflows.

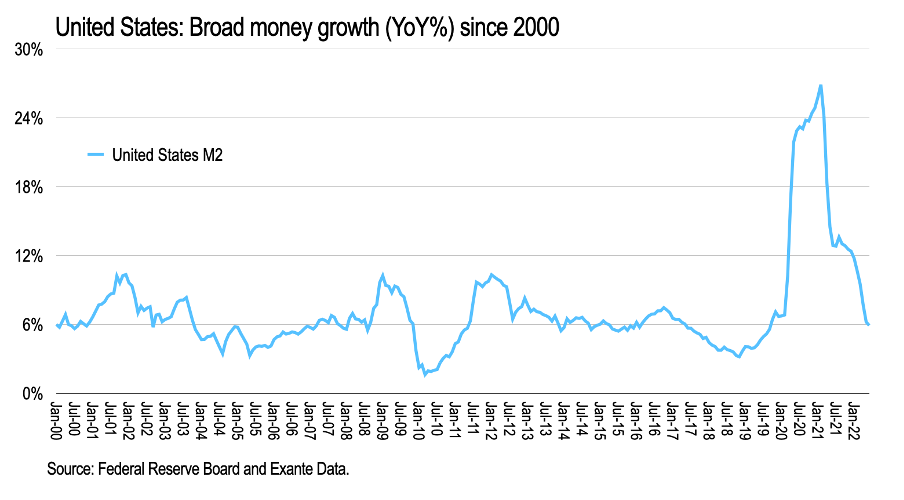

The variables that determine liquidity include interest rates, foreign flows, taxation and regulation, central bank policy, government spending, demographics and others. Economists and strategists who construct a composite index may disagree on which variables should be weighed more than others. For now, we simplify by looking at M2 money supply as an adequate if imperfect proxy.

Because central banks are the main actors in the liquidity equation, a fund manager’s mantra is “don’t fight the Fed.” It is a recognition that liquidity is more powerful than nearly all factors, including valuations or other company-specific factors.

Market history has repeatedly validated this advice. Consider the most vivid recent examples of abnormal liquidity impacting the equity market:

In 1997-99, the Fed lowered interest rates to help the economy and increased liquidity to address the Asian debt crisis, the Long Term Capital (LTCM) collapse and the Y2K computer bug. This propelled the equity market to fresh highs that were in most cases unwarranted by fundamental analysis. The bubble later deflated when the Fed withdrew liquidity in 2000.

The 2006-08 housing bubble was in part seeded by interest rates that were kept lower for longer after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Unlike the managed decline of 2000-02, this bubble ended with the crash of 2008.

And the 2020-21 bull market was fed by large injections of money by the Fed and by Congress. At the end of 2021, CPI inflation had climbed to 7% and it seemed inevitable that the Fed would withdraw liquidity in the new year.

Because the large tech companies — the FAANG+ aka MAAMANT, Meta, Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, Nvidia and Tesla) had been the main beneficiaries of easy money, we believed that these names would be hit hardest in the decline and wrote at the time that investors should sell the MAAMANT in 2022. Between January and June, they fell by an average 30% while the S&P 500 fell 20%.

So where do we stand today? The Fed arguably remains behind the curve. In retrospect, the timing and extent of the first rate hikes seem barely believable: 0.25% on March 17th and 0.50% on May 5th at a time when CPI inflation reached 8.5% and 8.6%.

Today, the Fed is still signalling an aggressive intent to withdraw liquidity just as it had earlier in the year, but negative real rates suggest that it remains de facto accommodative. This contradiction makes the “don’t fight the Fed” mantra ambiguous. Should investors “not fight Fed” by abiding by Fed rhetoric or should they not fight the Fed by watching Fed actions and real rates? In the first case, an investor would be bearish or cautious; in the second, he would be bullish. This confusion has led to the current tug of war between two groups of investors, those who go by the rhetoric (they tend to be value investors and generally bearish) and those who watch the actions (they tend to be growth investors and generally bullish). And this tug of war has played out this year in the market through several large declines alternating with violent rallies.

The net of it is that the Fed is not omnipotent and has to react, even if belatedly, to inflation figures.

In particular, it will be loath to repeat the mistakes of the 1970s when it stopped tightening too soon and inflation roared back after a short reprieve on two separate occasions. Our best guess therefore is that the Fed will err on the side of overshooting in order to kill inflation and to avoid a repeat of the 1970s. In the latest rally, the S&P 500 rose 17.7% (as of August 12th) since its intra-day low of June 17th, giving more breathing room for the Fed to continue withdrawing liquidity.

Because this latest rally was driven in part by a decline in commodity prices, bullish investors see the last few weeks as a return to normal business after a difficult first half. However, they may be ignoring that inflation was already at 7% in December, before commodities accelerated upward. It would be premature therefore to assume that inflation has been tamed because commodities have partially receded.

When considering market liquidity, no picture is complete that does not give some consideration to the dollar and to cross-border flows. The strong dollar this year has impacted the results of multinational corporations but it has also encouraged foreign investors to come back to the United States. To a US investor, the S&P 500 is down 10% and the Nasdaq100 17% year to date, but to a European investor, they are only down 0.5% and 8% in Euro terms. To a Japanese investor, the S&P 500 is up 5% year to date, and the Nasdaq100 is only down 2%. It is difficult to overstate the attractiveness of US assets to foreign investors if one surveys the regional challenges posed in Europe by the Ukraine war and in Asia by China lockdowns and Taiwan tensions. Foreign flows have also returned strongly to some segments of the real estate market and they may also explain the strength of the treasuries market.

Empirically, the evidence that liquidity has not been sufficiently drained can be seen in the renewed vigor in more speculative vehicles such as cryptocurrencies and some meme stocks. It can also be seen in the near complete absence of fear among younger investors.

Manufacturing PMI

Liquidity is essentially a financial consideration. Of more purely economic import is the manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (M-PMI) which surveys hundreds of supply chain managers in nineteen separate industries on the direction of manufacturing activity. The M-PMI is useful because it tends to be sticky from month to month and is a leading indicator of the economy and equity market. Of more particular interest within the survey is the New Orders component of the M-PMI.

We can see in these charts that the M-PMI and M-PMI New Orders, while not perfect predictors (no one measure is), have on multiple occasions signaled a turn in S&P 500 operating earnings and in the index itself.

The latest readings of the M-PMI remain above 50 but the index has been declining all year, suggesting deteriorating conditions. The M-PMI New Orders has dipped below 50, indicating contraction. This direction is confirmed by several regional Fed surveys. See for example the reports from the NY Fed and Dallas Fed. The Dallas Fed states the following:

Growth in Texas factory activity continued at a modest pace in July… The production index, a key measure of state manufacturing conditions, was largely unchanged at 3.8, a reading well below average but still indicative of growth.

Other measures of manufacturing activity painted a mixed picture again this month. The new orders index remained negative at -9.2, down from -7.3 in June, suggesting a further decrease in demand.

Perceptions of broader business conditions worsened in July. The general business activity index declined five points to -22.6. The company outlook index posted a fifth consecutive negative reading but moved up from -20.2 to -10.8. The outlook uncertainty index came off its two-year high of 43.7, falling to 33.7.

Politics / Geopolitics

Finally, consider some exogenous macro trends or events that may not be US-based or financial or economic but that nonetheless have a direct impact on the equity market or on sectors or companies. Here are two useful bits of advice in this direction:

First, to pay attention to events overseas. Because many crises originate outside US borders, keeping an eye on developments abroad can help a US manager avert significant drawdowns. It is easy to surmise that one of the main contributions of an international division at an asset management firm is its ability to discern brewing crises before they become headlines in the United States. For example in 1998, signs of an impending crisis were already evident in Europe several weeks before the Long Term Capital sell-off started in the summer. And again in early 2020, the spread of Covid was better understood in Asia and in Europe while it was downplayed by US politicians and asset managers.

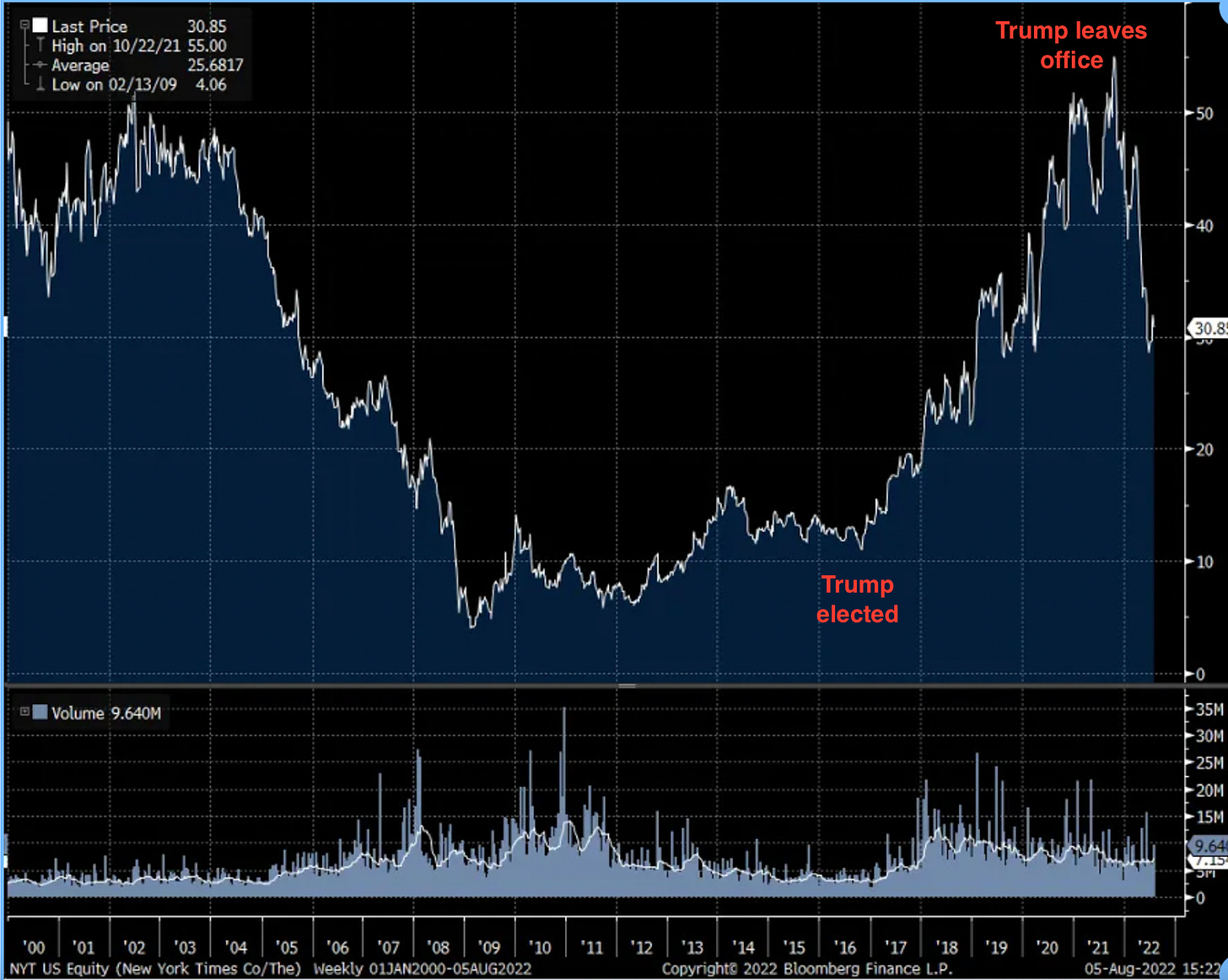

Second, to understand how politics impact different sectors. Some political developments (at home or abroad) are more favorable to some sectors than to others. For example, the Clinton years were highly favorable to intellectual property assets (software, telecom, media etc.) and culminated in 1998-2000 with a bubble in the pricing of those assets. But the Bush years (2001-08) were highly favorable to hard assets (mining, energy, real estate) and culminated in 2006-08 with a bubble in the pricing of those assets. Looking at matters with even more granularity and with a contra angle in this case, the election of Trump in 2016 led to a big surge in mainstream media revenues. After years of decline and stagnation, the stock of the New York Times started to rally after Trump won and it peaked nearly 500% higher when he left office.

The New York Times Company (NYT) stock price 2000-22

Many such events have precipitated themselves on the consciousness of unwilling fund managers this year. Today, we have to contend with the uncertainties of the Ukraine war, rising tensions between China and the US over Taiwan, an upcoming midterm election, and continued stress from the January 6th hearings. As a case in point, a surprise development in the Ukraine war, be it in the direction of ceasefire or of escalation, could quickly move indices 10% or more.

The midterm elections in the US could also swing investors’ appetite for risk or induce them to alter their sector weightings. Although the market has historically done well under both parties, there have been some watershed moments around elections, notably the 1994 midterm elections or the 2004 presidential election, when the victors were perceived as friendlier to the overall market or more supportive of some sectors vs. others.

Remarks

These are only three of the proximate macro factors that we deem most impactful on the markets. Current conditions call for caution, in particular as we write this on the heels of a swift 17.7% rally in the S&P 500. Inflation will likely remain an adverse factor that requires more liquidity drainage (although the July CPI is encouraging, nearly all of the improvement has come from lower energy prices). Manufacturing surveys still indicate a slowdown. And the stakes overseas are higher than they have been in a long time.

The combination of equities and the dollar made the US a haven of stability in 2022. Like others, we generally subscribe to Otto von Bismarck’s famous dictum that “there is a special providence for fools, drunks, and the United States of America”, and by extension for the US stock market.

However, we also believe that this providence endures mainly because it is periodically calibrated by a reversion to reality (as in valuations that make sense) and to accountability for unmet promises (as for hyped-up narratives), and that this reversion has been attained in the past either through a managed adjustment (as in 2000-02) or through a disorderly crash (as in 2008-09).

The content in this piece is partly based on proprietary analysis that Exante Data does for institutional clients as part of its full macro strategy and flow analytics services. The content offered here differs significantly from Exante Data’s full service and is less technical as it aims to provide a more medium-term policy relevant perspective.

Exante Advisors, LLC & Exante Data, Inc. Disclaimer

Exante Data delivers proprietary data and innovative analytics to investors globally. The vision of exante data is to improve markets strategy via new technologies. We provide reasoned answers to the most difficult markets questions, before the consensus.

This communication is provided for your informational purposes only. In making any investment decision, you must rely on your own examination of the securities and the terms of the offering. The contents of this communication does not constitute legal, tax, investment or other advice, or a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. Exante Advisors, LLC, Exante Data, Inc. and their affiliates (together, "Exante") do not warrant that information provided herein is correct, accurate, timely, error-free, or otherwise reliable. EXANTE HEREBY DISCLAIMS ANY WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.