TWO ISSUES ought to feature prominently in the Bernanke Review into Bank of England post-pandemic performance, a review led by former Fed Chair and Nobel Laureate Ben Bernanke, the terms of reference for which were published last month.

First, inflation and macro forecasts since the pandemic in the Monetary Policy Report (MPR)—the models and processes, the role played by money, how global developments are weaved in, and the use and abuse of associated fan charts.

Second, the logic of setting policy on the basis of incoming data instead of inflation forecasts while conditioning on the market path for Bank Rate—instead of using internal thinking to steer forecasts and, by implication, the market. Or, should the market lead or follow policymakers?

Much has changed since 1997…

Scope

Growing discontent with the performance of the Bank of England since the pandemic has seen commissioned by the Bank’s Court of Directors a Review led by Bernanke; the Court includes the Governor and Deputy Governors as well as non-executive members, a body charged with overseeing strategy and budget. It certainly looks like an attempt to see off external criticism.

The terms of reference underline that the “purpose of this review is to develop and strengthen the Bank’s processes in support of the Monetary Policy Committee’s forward-looking approach to the formulation of monetary policy, especially in times of high uncertainty” (emphasis added, see below.)

It is explicitly not an “ex-post review of policy decisions.” But it will “consider the appropriate approach to forecasting and analysis in support of decision-making and communications;” the processes, analytical framework, and role of the forecast, “including the roles of the MPC and the staff” in its development; and “the appropriate conditioning assumptions in projections.”

Bernanke will be “supported by the Bank’s Independent Evaluation Office” meaning there will be a considerable hold over the pen inside the Bank. We should lower our expectations.

But the Review represents a rare opportunity for thinking from outside the UK policy establishment to critically appraise UK monetary arrangements, an opportunity that should not be wasted.

1. Inflation and macro forecasts

Bank of England macro forecasts since the pandemic have been confusing, certainly for Bank Watchers, suggestive of problems with the models and processes—though such models are sufficiently “black box” that it is impossible for the outsider to unpick exactly what is going wrong.

While a full evaluation is impossible from this distance, we can summarise elements of the forecast to clarify when, and speculate why, these errors occurred.

Fan charts

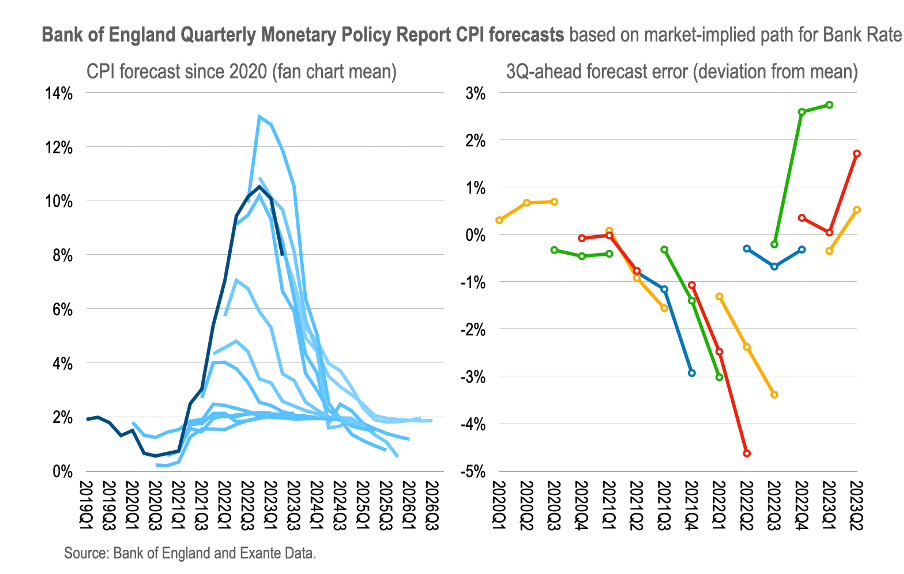

Begin looking at headline consumer price index (CPI) outcome compared to the mean of the fan chart projection—i.e., the probability weighted forecast, or expectation of inflation—based on the market path for interest rates. With this, we can visualise the deviation of forecast from actual inflation.

The chart below (left side) shows each MPR forecast for the period from Jan. 2020 through Aug. 2023; there are only fourteen forecasts from the fifteen MPRs as no fan chart produced in May 2020 at the height of the pandemic.

This omission immediately raises questions. It might be useful to recall why the fan chart was developed, as explained back in 1996:

The aim of the fan chart has been to convey to the reader a more accurate representation of the Bank’s subjective assessment of medium-term inflationary pressures, without suggesting a degree of precision that would be spurious.

As such, the fan chart works best as a vehicle to convey the MPC’s collective judgment on the changing distribution and skew to future inflation outcomes over a multi-year horizon. The discipline of building the fan chart, weighing the different subjective risks, itself helps to inform the policy strategy.

At a time of immense uncertainty such as during the pandemic, dropping the fan chart represents a missed opportunity to carefully weigh and communicate the risks ahead. And doing so also undermines its original purpose—suggestive of a changing attitude to the process of inflation forecast targeting compared to the early days of Bank independence. Why drop the fan chart during the pandemic when it could have served as a useful vehicle for setting out MPC views?

Serial correlation and the forecast skew

In any case, four observations on the remaining projections can be made:

First, there was serial correlation in the forecast errors. The right chart above shows only the three-quarter ahead forecast error for each vintage, where the first quarter is the also period when the MPR was produced—for which only part of the quarter’s data was available. Beginning with the 2020Q3 MPR, the forecast understated actual inflation three-quarters ahead at every forecast for the next two years with the size of the error increasing at every revision but one. Such forecast undershoots have since been followed by three forecasts where inflation has been over-stated—and we venture to guess that such over-shooting will continue for several more quarters during the inevitable disinflation. It is curious how, during the rational expectations revolution, economic actors were expected to avoid systematic forecast errors such as serial correlation, yet professional macro forecasters routinely suffer such flaws.

Second, while it is true that the largest three-quarter ahead forecast error was that made in 2021Q3—an error of 4.6ppts that followed the invasion of Ukraine and associated energy price spillovers—large errors still occurred during periods that did not capture the invasion period, such as the 2021Q2 forecast through 2021Q4 which still saw a 2.9ppts error. Perhaps, one might argue, this was the result of geopolitical gas price manipulation that could not be foreseen in early 2022. Yet the MPC failed to read into this signal further upside risks to energy prices ahead. In fact, the 2022Q1 MPR, published several weeks before the invasion, noted “two‐sided risks around the medium‐term inflation outlook… [with] energy and global tradable goods prices on the downside.” So energy was considered a downside risk to the inflation forecast while prices were, admittedly with blinding hindsight, signalling the opposite.

Third, the largest overshoot, of 2.7ppts, was that from 2022Q3 when future energy bills were expected to hit headline inflation and household pockets before any political consensus on an energy price cap was reached. But this offers a useful case where the fan chart could be used more aggressively. Indeed, the baseline forecast is, as is typical, conditioned on existing policies. Yet sometimes policies are likely to change, in this case in a way that was described afterwards by the Bank’s Chief Economist as “anticipatable and anticipated,” so this should be built into the forecast—a “subjective assessment” that could be added by the MPC by adjusting the fan chart skew. Curiously, during the 2022Q3 forecast round, the MPC indeed included a record skew over the 12 months ahead. But this was a positive skew—thus of the wrong sign, contributing to a higher mean inflation rate. The mode forecast from the Bank’s models for CPI at that time was 10.8%YoY for 2023Q2, shifted up 11.9%YoY due to the skew. Curiously, given that the out-turn was 7.9%YoY, with the energy price cap playing a large role, a substantial negative skew would have been more appropriate if the intervention was indeed anticipated. Of course, there were other drivers of the skew, but the Bank is not transparent on these different judgment inputs and their weights.

Fourth, more generally, it is curious to observe how the skew to the fan chart, discussed previously here, was hardly employed at all during the early stages of recovery from the pandemic, during initial period of persistent inflation overshooting, but was then used aggressively to revise up the forecasts at exactly the moment when inflation forecasts began to overshoot actual CPI. In this way, the MPC became a useful contrarian indicator for headline, if not core, inflation prospects.

In summary, prior the Ukraine invasion though in light of the post-pandemic reflation, a bias towards understating inflation began to emerge—and the forecast errors were on a rising path. There was no noticeable effort in Bank thinking to reflect quickly on a potential structural break in the inflation process, perhaps contributing to serially correlated forecast errors. These errors were further exacerbated when risks from an energy price run-up were initially understated until after the invasion when energy-related risks were thereafter over-stated as the Bank failed to reflect the inevitability of a price cap. This asymmetry, and the failure to reflect on, and adequately build, a sensible skew to the fan chart baseline, has arguably exacerbated forecasting errors on both sides.

When first introduced, the fan chart was heralded as an innovation that would help improve the communication in the context of inflation forecast targeting—by de-emphasising the point forecast while incorporating careful MPC judgments on the distribution of possible inflation outcomes. Recent experience suggests, admittedly from a distance, that the art of judiciously building the fan chart and carefully weighing risks to each side of the distribution has been forgotten.

Money and the global outlook

Two further issues are worth considering, especially in light of public interest in such matters.

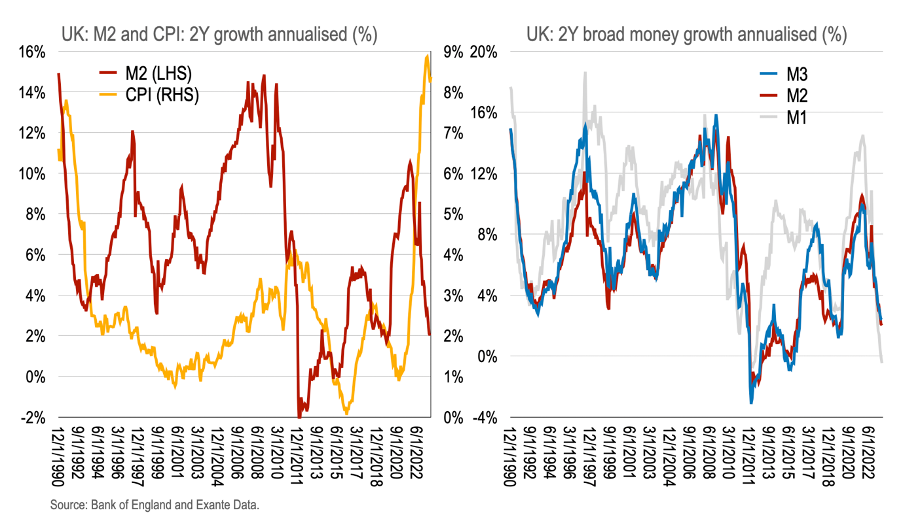

The first is the role played by money aggregates in forecasting inflation. It has not been lost on outsiders that the Bank no longer leans heavily on monetary aggregates despite their mythical status. The chart below shows the 2Y growth of inflation and various money aggregates in the UK, all annualised. M2 appears the most interesting.

While it is true the relationship between broad money and inflation was not particularly reliable in the period between 1990 and 2009, a period of intense globalisation, the peak in money growth at least appears to pick the top in the inflation cycle. And since 2009 the the relationship appears much closer, with M2 providing a good lead on UK inflation—though an additional energy-related overshoot for inflation over the past year has seen the growth of CPI unusually exceeding M2.

Certainly, broad money aggregates have been unreliable and modern macro finds little place for money. Goodhart’s Law reminds us that once a measure of money becomes a target for policy it ceases to be a useful measure. Perhaps a corollary of this is that once a macro variable gets ignored it begins to trace out useful statistical regularities once more.

In any case, Bernanke could provide a useful public service by spelling out what role money plays in UK monetary policymaking—and what role it ought to play.

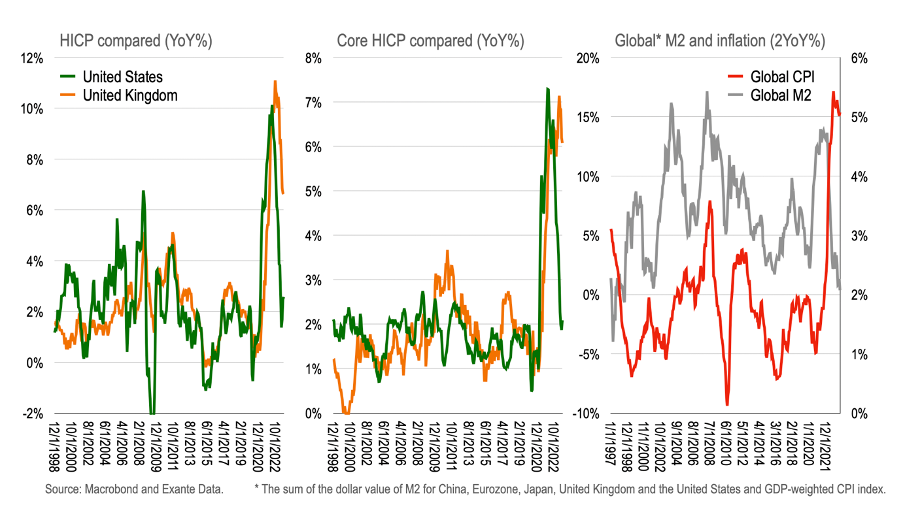

A second issue is the weight placed on international developments in the inflation forecasts and UK policymaking.

For example, it has been pointed out that UK inflation has roughly followed a comparable measure of US inflation, though with a six month lag, as shown in the chart below (left and middle panel.) Indeed, UK headline inflation historically looks like a moving average of United States HICP, indicative of a close historical link between inflation performance. Core HICP is less clear, with UK core jumping above US core after periods of sterling dislocation. But clearly forecasts could be improved by drawing on international experience.

The bigger picture still is the potential for a close link between global monetary developments and inflation. A measure of global M2 (a simple sum of dollar values of M2) maps into the turning points for a weighted CPI measure (right panel)—with global M2 occasionally leading or at least contemporary with inflation turns.

It’s difficult not to recall the inflationary consequences of the acceleration in Chinese M2 in the post-GFC decade, for example—necessary to prevent global stagnation.

If inflation is a global monetary phenomenon, then failing to reflect not only on UK money growth but her global counterpart could blinker the MPC when projecting and responding to inflation. The first danger is failing to forecast near-term inflation developments; the second is believing that policy should respond as if the inflation outcome were a purely domestic rather than a global phenomenon.

The theme that there has been a tendency to embed macroeconomic thinking in a closed economy rather than in a global framework is an old one. Of course, teaching macroeconomics from the closed economy perspective originates with the General Theory, whereas the Tract and Treatise were both concerned with the international dimension.

As Harry Johnson reflected in his lectures on Inflation and the Monetarist Controversy in the early-1970s:

In retrospect, I believe, Keynes can be legitimately and strongly criticised for for a sophisticated type of intellectual opportunism… which has had seriously adverse long-run effects both for the welfare of his own country and for the relevance of economics… [for he] produced a theory of unemployment which laid the blame for it on the inherent nature of capitalism itself, or by implication on the failure of the authorities to use domestic fiscal and monetary policy effectively, rather than on the international monetary system and on Britain’s relations with it. The consequence for British policy-making has been a pronounced and persistent tendency both to regard the country’s international economic relations as peripheral and concentrate instead on domestic fiscal and monetary measures as panaceas for the country’s chronic problems…

For academic economic theory, Keynes’s endorsement of the starting point of a closed economy whose authorities have potentially complete control over its economic destiny has been a powerful distraction from recognition of the reality of an increasingly economically integrated world economy containing an increasing number of economically relevant nations, most of which are atomistic competitors in the world economic system with little if any control over how that system develops.

Johnson was writing on the cusp of the transition between the Bretton Woods arrangements and the emergence of the floating rate period that followed.

Perhaps the balance of payments constraint no longer applies, so the closed economy assumption can be re-asserted? In fact, while the external financing constraint may appear to have been relaxed, the integration of economies has accelerated since, making the balance of payments in general and global monetary developments of ever-greater importance since.

Yet international developments often appear of peripheral concern in domestic policymaking still. The Bank of England does not publish a forecast for the UK balance of payments, for example.

2. Conditioning path and forecast targeting

Inflation forecasts are intended to guide policy by allowing Bank Rate to be set in a forward-looking way, to meet the inflation target over some sensible horizon while allowing for shocks. This was explained by Bernanke and Frederic Mishkin who, writing in 1997 about the policy strategy of inflation targeting, noted:

Despite the language referring to inflation control as the primary objective of monetary policy… inflation-targeting central banks always make room for short-run stabilization objectives, particularly with respect to output and exchange rates. This accommodation of short-run stabilization goals is accomplished through several means. First, the price index on which the official inflation targets are based is often denned to exclude or down-weight the effects of “supply shocks;” for example, the officially targeted price index may exclude some combination of food and energy prices, indirect tax changes, terms-of-trade shocks, and the direct effects of interest rate changes on the index (for example, through imputed rental costs). Second, as already noted, inflation targets are typically specified as a range; the use of ranges … to allow the central bank some flexibility in the short run. Third, short-term inflation targets can and have been adjusted to accommodate supply shocks or other exogenous changes in the inflation rate outside the central bank's control.

Inflation targeting came to mean, as Bernanke and Mishkin explain, setting a medium-term target for inflation and setting policy to achieve this target. The Bundesbank example from the early-1980s is particularly useful, as Bernanke and Mishkin continued, when such was the oil shock that inflation was brought back down slowly through a rolling target to reach 2 percent over a six year period.

Recall, the terms-of-reference for Bernanke note the role of forecasts in supporting the “forward-looking approach to the formulation of monetary policy, especially in times of high uncertainty.”

So far, we have focussed on baseline inflation forecasts under the conditioning assumption that future Bank Rate follows market-implied pricing. Notice how these forecasts in the first chart above often showed inflation falling below target over the forecast horizon—yet the Bank still raised the policy rate despite these forecasts.

The Bank also produces a forecast conditioned on unchanged policy. Comparing forecasts under the two conditioning assumptions provides some glimpse inside the black box.

The chart below shows, on the left, the difference between market pricing for Bank Rate over the forecast horizon over successive MPRs and the constant rate at that time. Initially the market envisaged cuts early in the pandemic; then gently increasing rates; later still, from early-2022, sharply increasing Bank Rate followed by later cuts—allowing it to resemble fingers rapping on a desk.

The chart also shows, on the right side, the deviation of the market-implied rate path from the constant rate path (x-axis) against the deviation of CPI under the market-implied versus constant rates (y-axis). In other words, the y-axis shows the difference in the inflation path due to following the market-implied rate path.

The projections are broken into four coloured groups. Initially, early in the pandemic, market pricing of cuts was reflected in higher forecast inflation if followed (2020Q1-2021Q1.) Next, as inflation picked up, the market began to price gently increasing interest rates so projected inflation is driven below the counter-factual of unchanged policy (2021Q2-2022Q1). By 2022, however, in light of the invasion of Ukraine and jump in energy prices, a rapid increase in Bank Rate followed by cuts began being priced by the market; this was associated with inflation being driven more aggressively below that delivered under constant rates (2022Q2-2022Q4). Finally, more recently, gentler hikes are being priced, from a higher starting point, followed by cuts; strangely, these paths are now associated with higher inflation—or, in the latest forecast, an inflation outcome that is virtually indistinguishable from that under unchanged rates.

The fact that the sign of the impact of higher rates on inflation has changed is a concern—higher rates in the near-term mean higher inflation over the relevant horizon? And the latest forecast which shows no material difference for inflation between holding Bank Rate constant or following the market suggests the Bank has simply given up.

Notice how, during several of these forecast rounds, holding Bank Rate constant brought about projected inflation closer to target. But the Bank raised rates regardless—possibly believing the market knew more than their models?

Yet the market is only interested in guessing that the Bank will do, and doesn’t care about inflation in 2-3 years except if this impacts policymaking. So if policy begins to ignore forecasts, the market will price higher rates based on sequential price pressure even if it comes from external sources with little impact on inflation 2-3 years out.

For the Bank to realise market pricing says nothing therefore about the prospect for meeting the inflation target—only that the market believe the Bank’s reaction function weighs contemporary outcomes over the forecast.

In this way, the market begins to lead policymakers rather than policymakers guiding markets.

Indeed, throughout this period MPC members continually, with one notable exception, refused to provide to the market guidance on Bank Rate, presumably so as not to be seen to be “wrong” at some point. But conditioning assumptions change, and so can their thinking. There is nothing wrong with that.

This has allowed the market to run away with front-end rate pricing in recent years, responding to incoming inflation prints by pricing ever-higher Bank Rate—to which, it seemed, the MPC felt obliged to respond. The one exception was in Nov. 2022 when the Governor pushed back against market pricing, showing that it can be done.

In summary, after the first meaningful negative supply shocks since inflation targeting was initiated in the UK, the Bank of England de facto stopped targeting the inflation forecast as they were expected but have instead been happy to dance to the market’s tune.

The alternative path of a proactive communication strategy to emphasise the inflation forecast and guide the market was discarded in favour of the reactive strategy of responding to incoming inflation via the market.

Overall, the Bank’s approach to conditioning on market pricing has brought two challenges:

First, the willingness to realise market pricing despite inflation forecasts has left little to anchor the gilt front end. The result has left asset prices susceptible to vagaries in incoming data rather than where inflation is most likely to be in 2-3 years. Policy errors and adverse consequences will follow.

Second, given the large moves in rate pricing, the Bank often goes into policy meetings with forecasts conditioned on an outdated path for Bank Rate—creating an additional communication challenge that can also become destabilising for the market. Such was the case in Nov. 2021. The cut-off date to lock in market pricing was 27th October with the yield curve for conditioning this forecast backed out using the average of market expectations for Bank Rate over the 15 working days before that. In the middle of this period interventions by Governor Bailey and colleagues caused a sudden repricing of expectations. After the cut off, Bank Rate moved further and prices in an an additional hike above that used for the conditioning assumptions. As such, the policy meeting involved discussing forecasts for inflation conditioned on the average of market pricing itself dislocated by the Bank’s communication strategy and placing weight on information nearly a month old.

Concluding remarks

No doubt the above remarks wander into “ex-post review” territory into which Bernanke should not drift. But it is difficult not to draw conclusions about the correct course for policy when discussing the inputs into the policy-making process.

The Bernanke Review reports in “the Spring” meaning there is plenty of time to reflect on these issues inside and outside the Bank to hopefully draw sensible conclusions—and make meaningful improvements to UK monetary arrangements.

We argue here that the key issues for Bernanke relate to the forecasting process and how this ties into the policy strategy in the context of inflation targeting.

In short: there may have been a structural break in the inflation process, reflected in serial correlation in the forecast errors; these errors could have been reduced by adequately reflecting on monetary and global developments; and that the inflation fan chart could have been better used to weigh the emerging risks and improve the baseline.

But strategy matters more.

The Bank appears to have de facto stopped targeting inflation forecasts and begun to set policy in reaction to their own forecast errors—including by allowing the market to lead the policy process rather than be guided by the Bank.

The Bank forecasting process can not doubt be improved considerably; but conditioning the forecast on a house view for Bank Rate would additionally force the MPC to “take back control” and lead the market again, as they should. This would have the additional benefit of returning focus once more to the forecast target rather incoming data—the latter with the potential for over-tightening and adverse consequences for mortgage holders and the real economy.

The content in this piece is partly based on proprietary analysis that Exante Data does for institutional clients as part of its full macro strategy and flow analytics services. The content offered here differs significantly from Exante Data’s full service and is less technical as it aims to provide a more medium-term policy relevant perspective. The opinions and analytics expressed in this piece are those of the author alone and may not be those of Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC. The content of this piece and the opinions expressed herein are independent of any work Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC does and communicates to its clients.

Exante Advisors, LLC & Exante Data, Inc. Disclaimer

Exante Data delivers proprietary data and innovative analytics to investors globally. The vision of exante data is to improve markets strategy via new technologies. We provide reasoned answers to the most difficult markets questions, before the consensus.

This communication is provided for your informational purposes only. In making any investment decision, you must rely on your own examination of the securities and the terms of the offering. The contents of this communication does not constitute legal, tax, investment or other advice, or a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. Exante Advisors, LLC, Exante Data, Inc. and their affiliates (together, "Exante") do not warrant that information provided herein is correct, accurate, timely, error-free, or otherwise reliable. EXANTE HEREBY DISCLAIMS ANY WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.

It strikes me that this exercise is entirely designed to create an outside scapegoat for future policy missteps and failures. I think the point that you make several times, but not strenuously enough, is that the BOE is afraid of leading because they are afraid if they are wrong, they will be held to account in the court of public, and potentially Parliamentary, opinion. and in the end, the one truth across all central banks I have observed is that no central banker is willing to admit their failures while still in the chair. maybe in a retrospective memoir when it no longer matters, but to think the MPC, and every central bank, will adopt changes that can be clearly understood is fantasy in my view.

One should never forget that Bernanke bears major reponsibility for crashing the US economy in 2008!